Evaluating the Essential Characteristics of Staff Cohesion and Collaboration:

Assessing This Summer What You Want to See This Fall (Part IV)

Listen to a summary and analysis of this Blog on the Improving Education Today: The Deep Dive podcast—now on the Better Education (BE) Podcast Network.

Hosted by popular AI Educators Angela Jones and Davey Johnson, they provide enlightening perspectives on the implications of this Blog for the Education Community.

[CLICK HERE to Listen on Your Favorite Podcast Platform]

(Follow this bi-monthly Podcast to receive automatic e-mail notices with each NEW episode!)

[CLICK HERE to read this Blog on the Project ACHIEVE Webpage]

[CLICK HERE to Set Up a Meeting with Howie]

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

Leadership is all about people. It is not about organizations. It is not about plans. It is not about strategies. It is all about people—motivating people to get the job done. You have to be people-centered.

General Colin Powell (1937 – 2021)

Colin Luther Powell was an American diplomat and Army officer who was the 65th United States Secretary of State (2001-2005) and the first African-American to hold that office. He also served our country as the 15th National Security Advisor (1987-1989) and the 12th Chairman of the Joints Chiefs of Staff (1989-1993). In this latter position, he oversaw Operation Desert Storm, the Persian Gulf War against Iraq (1990-1991).

His military approach to the Gulf War (called the “Powell Doctrine”) was to over-resource the depth and breadth of his fighting forces before embarking on war. This was one of the primary reasons that Operation Desert Storm lasted only 100 hours before a ceasefire was declared.

Colin Powell knew about leadership. He knew that successful organizations need good plans, good strategies, and good execution.

But, as above, he also knew that without motivated people working together as a team, the plans and strategies would not be executed with quality and consistency, and the desired outcomes would not occur.

_ _ _ _ _

This Blog (now, Part IV) continues the theme of our five-part Series emphasizing the importance—for districts and schools—of using the summer months to complete needs assessments and strategic plans in the five crucial areas of school improvement:

Part I. Quality Instruction

Preparing for Excellence This Coming School Year: Strategic Summer Planning to Transform Classroom Instruction (Part I)

_ _ _ _ _

Part II. Discipline and Classroom Management

School Discipline, Classroom Management, and Student Self-Management: The Summer Preparations Needed for Excellence This Fall (Part II)

_ _ _ _ _

Part III. Multi-tiered Services and Supports

The Characteristics of an Effective Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS): What You Need to Assess to Ensure Your Fall Success (Part III)

_ _ _ _ _

Part IV. Staff Cohesion and Collaboration

Part V. School Climate and Student Engagement

_ _ _ _ _

Today’s Blog focuses on the importance of and how to evaluate the essential characteristics of staff cohesion and collaboration now during the Summer, so that districts and schools can begin the new school year with the full-staff interactions and supports needed to go “to the next level of excellence.”

Describing and Analyzing Staff Cohesion

Staff cohesion involves unity, trust, and collaboration among school personnel—teachers, administrators, related services, and other support staff—who are all focused on shared academic and social, emotional, and behavioral goals and outcomes.

This focus is not just about getting along. It is about:

- Shared purpose. A collective commitment to student success;

- Mutual trust and respect. Open communication and psychological safety;

- Collaborative practices. Joint problem-solving, planning, and decision-making; and

- Supportive relationships. Emotional and professional support across colleagues.

In highly cohesive environments, staff members feel psychologically safe to share ideas, take risks, and offer one another support—both professionally and emotionally. Rather than operating in silos, teachers, administrators, and support staff function in multi-level teams that coordinate strategies, share resources, and align their efforts to continuously and consistently improve climate, instruction, engagement, and learning.

To build staff cohesion, schools must implement intentional practices. These include (a) establishing clear, shared goals; (b) scheduling time for regular collaboration; (c) sharing in joint professional development; (d) encouraging open communication; and (e) recognizing team accomplishments. When these elements are in place, the school becomes more than just a workplace—it becomes a community of learners where every individual contributes to, and benefits from, collective success.

Leadership plays a pivotal role in fostering staff cohesion. Research studies underscore the importance of principals and school leaders building trust, encouraging shared decision-making, and cultivating professional learning communities. These studies also reveal that when school leaders actively involve teachers in planning and empower them to contribute to school-wide decisions, cohesion strengthens, and staff are more likely to commit to collective goals. Ultimately, this leads to higher-quality teaching, a more positive school climate, and improved student achievement.

Going deeper. . . the benefits of staff cohesion ripple across the many layers of a school and district. For students, cohesive staff teams foster consistent instructional practices and stable classroom environments, they feel more emotionally supported and academically engaged, and more equitable support is seen across diverse student populations.

Educators also experience significant benefits in cohesive workplaces. Multiple studies show that strong collegial relationships increase positive interactions, job satisfaction, morale, and staff retention. Staff members tend to report lower levels of burnout, and to feel higher levels of professional fulfillment.

And all of this contributes to staff retention and lower levels of staff turnover—an issue that often undermines a school’s culture, instructional quality, student outcomes, and momentum from year to year. Importantly, cohesive teams serve as powerful engines for professional growth, allowing for real-time feedback, peer observation, and the shared learning opportunities that elevate teaching practices.

Moreover, when initiatives—such as curricular reform or new instructional strategies—are introduced, staff in cohesive schools are more responsive and resilient, and they navigate these transitions in positive, productive, and self-accountable ways.

From a John Hattie perspective, all of this synthesizes into Collective Teacher Efficacy (CTE). CTE refers to a shared belief among educators in their power to positively affect student outcomes, independent of external circumstances. Hattie’s meta-analytic research finds that CTE has an effect size of 1.57—a level of impact that far exceeds most educational interventions when predicting student achievement.

In the end, staff cohesion is not just beneficial, it is transformational. This is clearly one of the primary reasons for its prominence as one of the five school success and improvement components that districts and schools need to evaluate each Summer. . . as they prepare for the Fall.

Seven Characteristics of Cohesion

In reviewing the research and practice, there are seven directly-related characteristics or pathways to staff cohesion. These are the characteristics that districts, schools, and other educational settings should evaluate now so that they determine the action steps needed to begin the new school year in a position of growth and strength.

These seven characteristics are described below along with the data-based questions (in the Summary) to ask now as part of a District or School Cohesion Needs Assessment:

- Communication

- Caring

- Commitment

- Collaboration

- Consultation

- Celebration

- Consistency

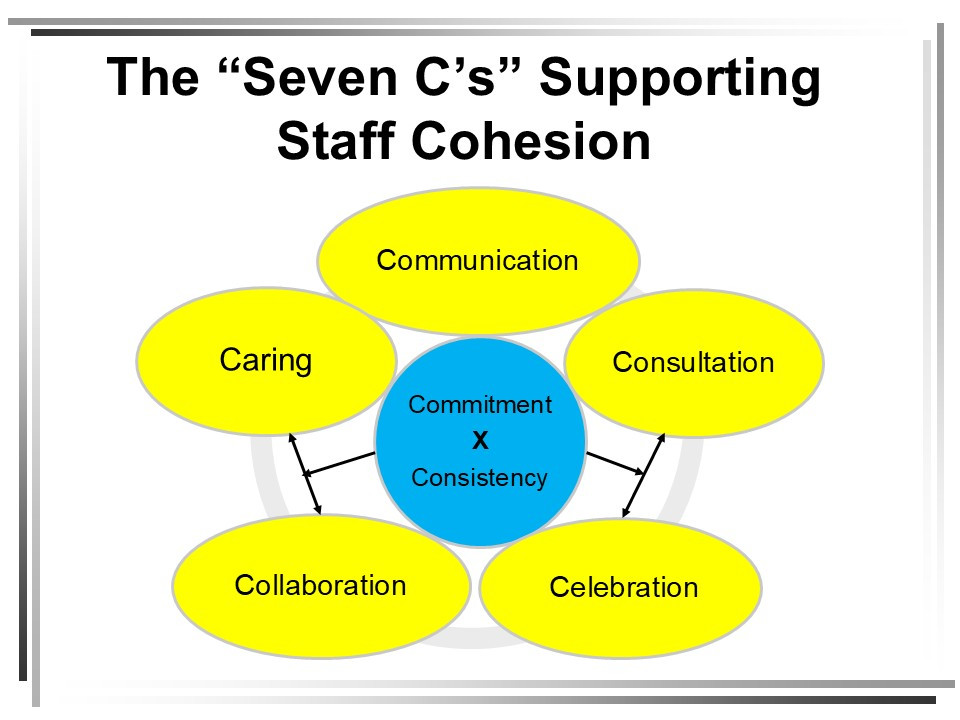

Significantly, these “7 C’s” are organized in a way that demonstrates that they are all interdependent with each other (see the Figure below).

More specifically, Commitment and Consistency are at the center of the processes. This is because successful staff are committed to the consistent demonstration of all of the other five interactions in everything that they do.

Indeed, successful staff demonstrate high and consistent levels of Communication, Caring, Collaboration, Consultation, and Celebration. But—because they are interdependent—each of these, when they occur, loop back to enhance others in the process.

Thus, for example:

- Celebration increases the probability of continued or enhanced Collaboration.

- Caring increases the probability of continued or enhanced Communication.

- Consultation increases the probability of continued or enhanced Celebration. . .

and so on.

Below, the 7 C’s are defined, described, and brief examples are provided for each one.

#1: Communication

Communication involves explicit and implicit formal and informal, oral and written person-to-person interactions. In an effective school, these focus on directing, involving, teaching, sharing with, reinforcing, or validating staff and colleagues who are working toward common goals.

Research consistently identifies clear, open, and frequent communication among school staff as a cornerstone of an effective school and student success. For example, research on the importance of relational trust in schools highlights how transparent and respectful communication builds trust, facilitates collaboration, and positively correlates with higher student achievement.

Other studies on professional learning communities and distributed leadership find that when staff communicate effectively—sharing ideas, concerns, and feedback—schools can more quickly identify and respond to student needs, adapt instructional practices, and align around shared goals—all resulting in, once again, improved academic, social, and behavioral outcomes for students.

There are two important dimensions of communication.

The first dimension involves a continuum from formal to informal communication. At one end of this continuum are formal communications that officially document or direct staff to do or accomplish specific things. Formal communications often come from administrators, supervisors, or lead teachers who hold positions of authority or responsibility over others.

At the other end of the spectrum are informal communications that occur on a collegial or personal level. Here, staff share information or perspectives, regardless of their position, that simply keep others up-to-date or informed of different situations or circumstances.

One significant communication challenge is to know where a colleague is “coming from” along this continuum. For example, what happens when administrators are communicating on an informal or collegial level, and yet their staff believe that—because of their “positions of authority”—they are communicating on a formal or official level?

When this occurs, staff sometimes take their administrator’s communication as an official position or directive—when it might simply be an opinion or request for input. Ultimately, this “misperception” may inhibit staff participation in what was intended to be an open process of sharing and collaboration.

The second dimension of Communication involves the form of a communication. In short, communication can be verbal or written, or non-verbal or symbolic.

Obviously, verbal or written communication is largely apparent, available, and “out there” for analysis and interpretation. Nonetheless, people respond or react to verbal or written communication not just on the content of the message, but on how it is delivered. That is, people respond to how direct a message is, the words or phrases that are used, and the emotionality that they “read into” the message.

Non-verbal communication includes, for example, the physical posture, hand gestures, or facial expressions that accompany a verbal message. Sometimes, the non-verbal gestures or facial expressions become more important than the verbal message.

For example, if a school principal is verbally describing a new district policy, but is non-verbally communicating that “this is not really important,” how do staff interpret and respond to the verbal message?

Similarly, if the same school principal is asked a question about the new district policy, pauses for ten seconds, and then asks for the next question, how is that interpreted?

Symbolic communications typically involve actions or the lack of actions. This is embodied in the phrases that emphasize that: “Actions speak louder than words”. . . and that people need to: “Walk the Walk”. . . instead of just “Talk the Talk.”

In this latter area, while many of us make good-faith commitments that we are later unable to honor (for understandable reasons), some people make commitments that they never intend to honor. For these latter individuals, their (in)actions speak louder than their words, and their symbolic communication reflects their (often self-centered) priorities and, sometimes, how little we can trust them.

In the end, Communication is an essential component that lays the foundation of staff cohesion. It is an interactive, two-way process.

For it to “work,” the words, meaning, intent, and emotions of the speaker must be accurately understood and interpreted by the listener. In addition, listeners must also note that what is not said is sometimes more (or as) important as what is said.

Given the complexities of the school and schooling process, speakers need to strive to communicate in clear and concise ways. Listeners need to take responsibility for clarifying unclear messages, and for “checking out” the accuracy of their interpretations.

#2: Caring

Caring involves the interest, recognition, understanding, validation, support, and reinforcement that we give to others in the professional, personal, interpersonal, relationship-related, and/or spiritual areas of their lives.

Underlying Caring is motivation. When we care about someone—whether on a personal or professional level—we are motivated to support, sponsor, invest, or interact with them.

But Caring is a behavior. If we do not see it, feel it, experience it, or believe it, we do not necessarily know that someone cares for us.

At a more functional level, there are multiple “targets” for caring. Moreover, caring (like communication) occurs on a spectrum.

Relative to targets, school staff can care about different people: (a) themselves, (b) their students, (c) their colleagues, (c) their school, and/or (d) their district or community.

They can also care about different processes: (a) relationships and interactions, (b) fairness and equity, (c) effort and productivity, and/or (d) outcomes and accomplishments.

Clearly, people care about these targets in different ways, at different times, to different degrees, and in different amounts.

Relative to the continuum, people can care too much or too little.

When they care too little. . . this could be negative or neutral. Negative caring typically results in motivations and actions that professionally, personally, or interpersonally “hurt” someone or that undermine a plan or initiative.

In contrast, when someone is “neutral” relative to “caring” about something, they either are totally unaware of the person or process (it’s “not on their radar”), or it is just not a priority for them (it’s flying “under their radar”).

At the other end of the spectrum, when staff care too much about something, this also can be unhealthy or counterproductive. Indeed, when staff care too much, they become so wedded to a person or process that they lose their objectivity, and their motivation and actions become obsessed, excessive, or extreme.

For example, when we personally care too much about colleagues, we may be more likely to miss, ignore, enable, or unconditionally accept their professional weaknesses, missteps, or even maliciousness.

Similarly, when staff care too much about themselves, then their motivation, decisions, and actions—relative, for example, to students or colleagues—become selfish, indifferent, or callous.

_ _ _ _ _

The importance of caring within school communities is well supported by research on school climate and teacher-student relationships. One meta-analysis found that teacher and staff warmth, empathy, and regard for others enhance classroom climate, increase student engagement, and reduce behavior problems.

When staff demonstrate caring for one another, it sets a prosocial norm that extends to students, fostering environments where students feel safe, supported, and valued. This emotional safety is fundamental for students’ risk-taking in learning, resilience, and development of social and emotional competencies.

_ _ _ _ _

In summary, staff in successful schools care about each other on a professional, personal, and interpersonal level. Thus, from the very beginning, schools need to hire staff who care, and then they need to consistently nurture, reinforce, and sustain “the caring” to support the mission, goals, and outcomes of the school.

But, just as in life, there is a “balance” or “happy medium” to all of this Caring. Too much or too little creates an imbalance that often undercuts or undermines student, staff, and school success.

The challenge is how to find, maintain, and sustain balance in a sometimes unbalanced student, staff, and school world.

#3: Commitment

Commitment involves staff conjoint dedication to a school’s ideals and beliefs, goals and objectives, and plans and programs that support students and families, colleagues and co-workers, organizations and systems, and communities and society. Commitment involves both attitudes and behavior. It is long-standing in nature, and it endures through good times and bad.

Collectively, we have already discussed how effective and consistent Communication creates interpersonal trust across a school,; while balanced and sustained Caring results in staff who are motivated to its mission, goals, and outcomes.

Both of these elements facilitate commitment—for individual staff, as well as for small (e.g., grade- or instructional-level teams) and large (e.g., within school or across district) groups of staff.

Critically, research evidence shows that staff commitment—shared dedication to school vision, goals, and persistence through challenges—drives improved school outcomes. Studies have found that when teachers believe in their school’s direction and feel invested in collective efforts, their instructional efficacy, innovation, and perseverance increase. This commitment translates to more consistent high-quality teaching and more equitable implementation of academic and behavioral systems—both predictive of greater student achievement and positive social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes.

_ _ _ _ _

But once staff commitment is established, it needs to be generalized and sustained across all of the other 7 C’s.

And so, schools must be committed to effective Communication, and sincere and authentic Caring in order to build and sustain Commitment. . . and then to the reinforcement of staff’s commitment to Collaboration, Consultation, Celebration, and Consistency.

Beyond this, rather than get into a lot of additional “detail” regarding Commitment, let’s “listen” to the wisdom of others:

- Tony Robbins said: “The only limit to your impact is your imagination and commitment.”

- Peter Drucker: “Unless commitment is made, there are only promises and hopes, but no plans.”

- Mario Andretti: “Desire is the key to motivation, but it’s determination and commitment to an unrelenting pursuit of your goal—a commitment to excellence—that will enable you to attain the success you seek.

- Margaret Thatcher: “You may have to fight a battle more than once to win it.”

- Jim Collins: “The kind of commitment I find among the best performers across virtually every field is a single-minded passion for what they do, (and) an unwavering desire for excellence in the way they think and the way they work.”

#4: Collaboration

Collaboration occurs when school staff work as teammates in well-functioning teams, and successfully:

- Plan, implement, evaluate, and celebrate projects together;

- Establish the commitment and consensus to succeed;

- Use data, problem-solving, and negotiation to resolve differences; and

- “Agree to disagree” when problem-solving is not completely successful—keeping disagreements on a professional, not personal, level.

Critically, Collaboration is different from cooperation.

Cooperation typically occurs when dyads or groups of staff agree on specific group goals, and then work together to attain those goals.

But some work group members may not support the group’s goals. When this occurs, these individuals may “opt out” and refuse to participate in group activities. . . or they may be “pushed out” of the group and not allowed to participate.

Thus, when a work group has a disagreement or conflict, cooperation becomes conditional. Moreover, the group tends to shift to an area of agreement—because they want to avoid or they do not have the skills or capacity to resolve the conflict.

Collaboration, in contrast, occurs when team members are able to work together both when there are agreed-upon team goals, as well as when there are individual or team differences and disagreements.

Thus, collaboration involves the willingness and ability:

- To take on different roles for the good of the team (e.g., sometimes “leading” and sometimes “following”);

- To positively recognize and reinforce team member and team strengths;

- To critically evaluate, provide feedback, and directly resolve individual and collective team weaknesses; and

- To function so that the “team is more valued than the sum of its individual members.”

Collaborative working environments have been repeatedly linked to both improved staff morale and student outcomes. For example, research has validated that schools with strong collaboration demonstrate higher student achievement gains. Moreover, research on Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) shows that when teachers work together to analyze student data, plan instruction, and engage in collective problem-solving, students benefit from more coherent instruction and more consistent behavioral expectations.

_ _ _ _ _

As alluded to above, workgroups often cooperate, while teams typically collaborate.

Significantly, school staff are often initially organized in work groups and given tasks to complete. And, while they are given the time to accomplish the tasks, they are rarely given the expectation, time, support, or resources needed to help them evolve into teams.

In successful schools, there is an explicit goal and expectation that all school work groups will ultimately become fully functioning teams. Clearly, this takes both administrative and staff commitment, collaboration, and—sometimes—coaching. And it only occurs by attending to and implementing all seven of the 7 C’s.

To summarize, think about the ways that Mark Sanborn differentiates between Work Groups and Teams:

- Teams are internally motivated; Work Groups are externally motivated

- Teams focus on a shared agenda; Work Group members focus on a personal agenda

- Teams are innovative, and members change roles to meet team goals; Work Groups are static, and member roles are fixed

- Teams share leadership and work from the middle; Work Groups have leaders who work from the top down

- Teams have self-starters; Work Groups have kick-starters

- Team members recognize that individual success means team success; Work Group members only care about individual success

- Team members are interdependent; Work group members are either independent or dependent

- Team members enjoy working with their colleagues; Work group members tolerate working with their colleagues

- Teams have a sense of urgency that facilitates performance; Work groups focus on deadlines, and they underperform when under pressure

- Teams thrive on challenge and focus on success; Work groups avoid risks and work to avoid failure

#5: Consultation

Consultation involves the recognition that—when school staff do not have the understanding, knowledge, skill, confidence, objectivity, or interpersonal capacity to address a need, meet a goal, or solve a problem—they must have the willingness to find, listen to, and accept assistance from colleagues, supervisors, or other experts who can help them.

By way of analogy: When doctors are unsure about a patient’s symptoms or diagnosis, or when they simply need some reassurance on a challenging case, they get a “consult” or a “second opinion.” This is an expected part of the “culture of the medical profession.”

Indeed, if a doctor did not do this, and his/her patient died, all of us would be thinking about medical malpractice.

Unfortunately, however, in many schools—in the presence of a significant student or staff challenge—asking for a consult or second opinion is often considered an admission of weakness or incompetence.

And so, many teachers or administrators literally or figuratively “close their door,” rationalize or deny the problem, and continue to implement the same approaches that are already not working. Moreover, some are thinking (and I am just being honest here), “The school year is eventually going to end, and the problem will be someone else’s next year.”

Picking up the medical analogy above. . . if a school consultation is avoided, the student problem debilitates his or her future, shouldn’t the avoidance represent educational malpractice?

_ _ _ _ _

Seeking consultative expertise from colleagues is a key pillar of school improvement and professional growth. Research on instructional coaching and peer consultation demonstrates that when teachers routinely access expertise from specialists or peers, they are more likely to implement evidence-based practices and adapt to student needs. This leads to increased instructional quality and more effective interventions for students with academic or behavioral challenges.

A school culture of consultation also normalizes lifelong learning and reduces isolation. The “bottom line” is that we need to make sure that the culture and practices of every school in our country focus on staff improvement, growth, excellence, and life-long learning; and that they explicitly support the mantra:

"If you don’t know, you get a consult.”

One way to reinforce this mantra involves the development of the “Consultation Staff Resource Directory”—discussed in Part III of this Blog Series. This Directory provides brief professional biographies of everyone, for example, in a school, specifically describing their areas of expertise and where they are available to consult with others.

We have done this in schools across the country by asking school (and other) staff to complete a simple two-page questionnaire describing: (a) their formal degrees and areas of certification or specialization; (b) their formal areas of in-service training and professional development; (c) their academic, behavioral, or other areas of experience and expertise; and (d) their special skills, talents, or hobbies.

The information from these questionnaires is then organized electronically into a Directory that is available on a school’s shared drive. Typically, the Directory has two sections.

Section I has all of the completed staff questionnaires, organized by grade level (or departments) and teachers, special teachers (e.g., music, art, PE, media, computers), support or related services staff (e.g., special education teachers, academic instructional consultants, counselors, school psychologists, nurses, etc.), and administrators.

Section II is organized by specific instructional or intervention skill areas—for example, phonetic decoding interventions, cooperative learning strategies and techniques, ways to motivate students. In each area, there is a list of all of the staff who are willing and able to consult with other colleagues.

With this Directory, teachers and others have a ready resource that they can use when they need consultation on a specific student problem. This not only reinforces the mantra above, but it also encourages staff to share their expertise on behalf of their students and colleagues.

#6: Celebration

Celebration involves the formal or informal, internal or external, individual or collective, and random or planned observances that acknowledge the accomplishment of short- and long-term student, staff, and school goals. While celebrating individual achievements is important, successful schools spend more time celebrating group and team successes.

School-based recognitions and celebrations of accomplishments are associated with higher staff morale, motivation, and cohesion. According to theory and practice, acknowledging effort and achievement reinforces intrinsic motivation. Schools that celebrate collective gains (e.g., improved reading scores, successful behavior interventions) see a boost in collective efficacy, which—as noted earlier—Hattie has noted as a consistent top factor in student achievement. This culture of recognition also models positive reinforcement practices for students, supporting a growth mindset.

But. . . school celebrations should focus on tangible and measurable student and staff outcomes—those that facilitate skill and progress and that result in actual achievements and proficiencies. Said a different way, celebrations of participation and process are purposeless if student outcomes are not realized. Schools must guard against bestowing “participation awards” alone.

In the end, schools and districts need to celebrate the processes that make every step of the educational journey successful. These celebrations fortify staff cohesion.

#7: Consistency

Finally, Consistency—along with Commitment—is the “glue” that makes the 7 C’s work.

Consistency involves staff members’ continuous dedication, focus, and acts of Communication, Caring, Commitment, Collaboration, Consultation, and Celebration.

Consistency occurs across time, people, settings, situations, and circumstances. It is essential for creating a predictable, fair, and trusting school environment for both adults and students. Research on organizational health shows that schools with consistent adult behaviors—whether applying rules or implementing routines—experience fewer behavioral disruptions, better attendance, and higher achievement. For students, consistency provides psychological safety and clarity about expectations—crucial elements for academic and behavioral success.

Indeed, as with communication, consistency breeds trust. And with trust, consistency becomes easier and easier.

Conversely, inconsistency undercuts motivation, and this negatively impacts staff cohesion and their commitment to and implementation of the 7 C’s.

For example, persistently inconsistent communication often results in staff frustration. Over time, this frustration results (along a continuum) in staff members who become angry, aggressive, and begin to actively act out. For other staff, inconsistent communication results in anxiety, and these staff members withdraw, become passive, and “check out.”

Similarly, persistently inconsistent staff collaboration often results where some staff would rather work alone, while other staff refuse to work at all—because they are unwilling to take the sole responsibility for specific tasks. Clearly, this is antithetical to building the staff cohesion needed to accomplish a school’s mission, goals, and desired student outcomes.

Summary and a Call to Action

According to Sanborn,

“A Team is a highly communicative group of people with different backgrounds, skills, and abilities with a common purpose who are working together to achieve clearly defined goals.”

In order for schools to be successful, their different teams need to be working cohesively on their different parts of the collective school and schooling process. But in order to have cohesive teams, school staff (and teams) need to understand and practice the 7 C’s that, collectively, facilitate their total cohesion.

While this is not easy, it is always necessary.

_ _ _ _ _

This is Part IV of our five-part Blog Series emphasizing the importance—for districts and schools—of using the summer months to complete needs and status analyses in the five crucial areas of school improvement:

- Quality Instruction

- Discipline and Classroom Management

- Multi-tiered Services and Supports

- Staff Cohesion and Collaboration

- School Climate and Student Engagement

To summarize this Blog on staff cohesion and collaboration, we provide seventeen data-based Needs Assessment Questions that school leaders can answer based on a review of their schools, teams, and staff members during the past school year.

After analyzing the answers to these questions, district and school leaders should develop an Action Plan in this area, integrating it with the Actions Plans developed after completing the Needs Assessments in the first three Blogs.

With some districts and schools already engaged in the professional development days leading to their 2025-2026 school year openings, it is still not too late to plan, schedule, and implement the activities needed to making the opening of school, and its first few months, successful.

The Cohesion and Seven C’s Needs Assessment questions are:

Communication

1. To what extent did staff report feeling informed about key school initiatives, changes, and decisions this past year?

2. What do staff climate or engagement surveys indicate about the clarity and timeliness of school-wide communication?

_ _ _ _ _

Caring

3. How do staff rate the sense of support and care from colleagues and administration, according to end-of-year or pulse surveys?

4. What patterns emerged in staff absences or turnover that might reflect underlying issues of connectedness or support?

_ _ _ _ _

Commitment

5. Based on participation data (e.g., voluntary committees, after-school programming), how consistent was staff engagement with school improvement efforts?

6. Were there observable differences in commitment between staff groups (e.g., grade levels, departments), and to what can these be attributed?

_ _ _ _ _

Collaboration

7. How frequently did interdisciplinary or grade-level teams meet, and what is the evidence of shared planning or co-created initiatives?

8. Did staff report that their collaborations led to changes in instructional practices or interventions that benefited students?

_ _ _ _ _

Consultation

9. To what extent did teachers and support staff seek out expertise or coaching when encountering student academic or behavioral challenges?

10. How accessible and utilized were consultation resources (such as instructional coaches, special education liaisons, or PLC leaders)?

_ _ _ _ _

Celebration

11. In what ways did the school recognize and celebrate individual and team successes during the year?

12. What percentage of staff felt their efforts and achievements were acknowledged meaningfully?

_ _ _ _ _

Consistency

13. How consistently were school-wide expectations and policies (academic, behavioral, procedural) implemented across classrooms and grade levels?

14. What discrepancies, if any, were noted between school policies and their practical implementation, as evidenced by discipline or incident reports?

_ _ _ _ _

Integration Questions

15. Looking at your school’s student outcome data (academic achievement, attendance, behavior), to what extent might strengths or weaknesses be traced to the presence or absence of staff cohesion?

16. When reflecting on major challenges or successes from the past year, how did staff cohesion (or lack thereof) play a role, according to staff debriefs or faculty meeting minutes?

17. What concrete evidence (surveys, observations, student data) suggests that your school climate supported or hindered the 7 C’s of cohesion, and where do the greatest opportunities for growth lie?

_ _ _ _ _

By using these research-informed lenses and targeted questions, school leaders can drive not only reflective assessment but also meaningful planning that builds stronger, more effective teams for adult and student success.

Tom Vilsack said,

“People working together in a strong community with a shared goal and a common purpose can make the impossible possible.”

We are looking for the possible, not the impossible.

Hopefully, this Blog and Parts I, II, and III can help.

Our Improving Education Today Podcast is Part of the Better Education (BE) Network of Top Education Podcasts in the U.S.

Remember that our Podcast . . .

Improving Education Today: The Deep Dive

with popular AI Educators, Davey Johnson and Angela Jones. . . is a full member of the Better Education (BE) Network of the top podcasts in education in the country!

This means that our Podcast is now available not just on Spotify and Apple, but also on Overcast, Pocket Casts, Amazon Music, Castro, Goodpods, Castbox, Podcast Addict, Player FM, Deezer, and YouTube.

Here's how you can sign up to automatically receive each new episode:

LINK HERE: Improving Education Today: The Deep Dive | Podcast on Spotify

LINK HERE: Improving Education Today: The Deep Dive | Podcast on Apple Podcasts

LINK HERE for All Other BE Education Network Platforms: Improving Education Today: The Deep Dive | Podcast on ELEVEN More Podcasts

Twice per month, Davey and Angela summarize and analyze the “real world” implications of our Project ACHIEVE bi-monthly Blog messages—adding their unique perspectives and applications on their relevance to you and our mission to: Improve Education Today.

These Podcasts address such topics as: (a) Changing our Thinking in School Improvement; (b) How to Choose Effective School-Wide Programs and Practices; (c) Students’ Engagement, Behavioral Interactions, and Mental Health; and (d) Improving Multi-Tiered and Special Education Services.

Davey and Angela have also created a Podcast Archive for all of our 2024 Blogs (Volume 2; see below), and the most important 2023 Blogs (Volume 1; see also below).

They will continue to add a new Podcast each time a new Project ACHIEVE Blog is published.

Many districts and schools are using the Podcasts in their Leadership Teams and/or PLCs to keep everyone abreast of new issues and research in education, and to stimulate important discussions and decisions regarding the best ways to enhance student, staff, and school outcomes.

If you would like to follow up on today’s Blog or Podcast, contact me to schedule a free one-hour consultation with me and your team.

[CLICK HERE to Set Up a Meeting with Howie]

I hope to hear from you soon.

Best,

Howie

[CLICK HERE to Set Up a Meeting with Howie]

[To listen to a synopsis and analysis of this Blog on the “Improving Education Today: The Deep Dive” podcast on the BE Education Network: CLICK HERE]