School Discipline, Classroom Management, and Student Self-Management:

The Summer Preparations Needed for Excellence This Fall (Part II)

Listen to a summary and analysis of this Blog on the Improving Education Today: The Deep Dive podcast—now on the Better Education (BE) Podcast Network.

Hosted by popular AI Educators Angela Jones and Davey Johnson, they provide enlightening perspectives on the implications of this Blog for the Education Community.

[CLICK HERE to Listen on Your Favorite Podcast Platform]

(Follow this bi-monthly Podcast to receive automatic e-mail notices with each NEW episode!)

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction: Students’ Classroom Behavior is Not Improving

Now multiple years after our “full return” (Fall, 2021) from the pandemic, students’ classroom behavior is not getting better.

A January 8, 2025 Education Week article reported on a mid-December 2024 survey of 990 educators (134 district leaders, 97 school leaders, and 759 teachers)—chosen as a nationally-representative sample by the EdWeek Research Center.

The results of this survey indicated:

- 72% of educators said that the students in their classroom, school, or district have been misbehaving either “a little” (24%) or “a lot” (48%) more than in the fall of 2019, the last semester before the COVID-19 pandemic began.

In contrast:

- A year ago (early 2023), 70% of educators said that their students were misbehaving either “a little” (36%) or “a lot” (33%) more than in the fall of 2019; and

- In 2021, 66% of educators said that their students were misbehaving a little or a lot more than in the fall of 2019.

The Education Week article went on:

"Student misbehavior has routinely topped teachers’ lists of concerns and most pressing challenges in recent years. There’s been a pronounced spike in behavior problems, ranging from minor classroom disruptions to more serious student fights broadcast on social media, since students returned to school buildings. Teachers have also reported a drop in students’ motivation in that time period.

Student misbehavior is hurting staff morale, some survey respondents said.

Indeed, past surveys have documented this overall dip in teacher morale. An annual report released in August by the EdWeek Research Center showed that just 18 percent of public school teachers said they are very satisfied with their jobs, a much lower percentage than decades ago, and a slight drop from the year prior when 20 percent of teachers said the same.

In that same report, many elementary and middle school teachers said they need more support in dealing with student discipline, and that the additional help would improve their mental health. Eighty percent of teachers reported they have to address students’ behavioral problems “at least a few times a week,” with 58 percent saying this happens every day, according to a Pew Research Center report from April 2024."

Students are Not Going to “Fix” Themselves: What School Leaders Need to Assess this Summer

While it is easier to just “blame the students, the parents, residual pandemic trauma, cell phones in the classroom, and social media” for students’ persistent behavioral challenges, this externalization is not going to solve the problem.

And the students are not going to fix themselves.

Moreover, there are no quick fixes (otherwise, this problem would have been solved long ago). . . and the “frameworks” advocated through SEL (whatever that is) and PBIS (now 30 years old) have not worked either.

Consistent with the theme of this Blog Series (today is Part II), if districts and schools are going to open the 2025 to 2026 school year in August (or September), they need to address all five of the school improvement characteristics in this five-part Blog Series:

- Quality Instruction

- Discipline and Classroom Management

- Multi-tiered Services and Supports

- Staff Cohesion and Collaboration

- School Climate and Student Engagement

_ _ _ _ _

We addressed Quality Instruction in Part I of this Series:

Preparing for Excellence This Coming School Year: Strategic Summer Planning to Transform Classroom Instruction (Part I)

There, we outlined seven research-proven core characteristics of effective classroom teachers, seven research-to-practice characteristics of effective teaching teams, and seven characteristics of effective instructional/intervention support systems and staff.

We then encouraged schools to compare their current status and evaluation data against these 21 characteristics to develop and begin the implementation of strategic Action Plans. . . targeting the beginning of the new school year and beyond.

Our parting Call to Action asserted that the summer months offer districts and schools a "unique and invaluable opportunity for reflective analysis, strategic planning, and skill development."

We noted that the ultimate choice for educational leaders—right now in June—is "between preparation versus procrastination, systematic improvement versus wishful thinking, and investing in summer planning versus accepting the status quo this Fall."

_ _ _ _ _

Knowing that the five improvement areas above are interdependent, in today’s Blog, we discuss the research-to-practice components and characteristics of effective School Discipline, Classroom Engagement and Management, and Student Self-Management.

Similar to Part I, we detail this at the school, grade and classroom, and related services/support staff levels.

The ultimate goal here for districts and their schools is to teach students, at their different developmental levels from preschool through high school, the social, emotional, and behavioral self-management skills that they need for current and future success.

Said a different way: All students need to progressively learn, master, and be able to apply effective interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional awareness, control, communication, and coping skills in their classrooms and across the common areas of their schools.

All Politics is Local: Applying Evidence-Based Components to Individual Schools

Thomas “Tip” O’Neill, Jr. (1912 – 1994) was the 47th Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1977 through 1987—the third-longest tenure in history and the longest uninterrupted tenure. During his first political campaign in 1935, he popularly said, “All politics is local.”

What he meant is that everything done at the national level (i.e., in Washington, D.C.) should be done with the local community populace in mind.

The point here is that all evidence-based blueprints—the blueprints below that specifically relate to school discipline, classroom engagement and management, and student self-management—need to be applied and individualized to every local school and district.

Indeed, because of the diversity across even local districts that are geographically next to each other, education cannot be a “one size fits all.”

While schools may all need to wear “gloves,” some schools need warm gloves, others need work gloves, and still others need a different-sized glove than the school down the road.

_ _ _ _ _

Beyond the school discipline goals introduced above, deeper goals are typically needed. In total, they may involve the following:

Student Goals.

As above. . . Establishing students’ social, emotional, and behavioral competency and self-management as demonstrated by:

- High levels of effective interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional coping skills and behaviors by all students;

- High levels of critical thinking, reasoning, and social-emotional application skills and behaviors by all students; and

- High levels of academic engagement and academic achievement for all students.

_ _ _ _ _

Staff Goals. Facilitating:

- High levels of effective instruction and classroom management across all teachers and instructional support staff; and

- High levels of teacher knowledge, skill, and confidence relative to analyzing why students are academically and behaviorally underachieving, unresponsive, or unsuccessful, and to implementing strategic or intensive academic or behavioral instruction or intervention to address their needs.

School Goals. Producing:

- High levels of positive school and classroom climate, and low levels of school and classroom discipline problems that disrupt the classroom and/or require office discipline referrals, school suspensions or expulsions, or placements in alternative schools or settings;

- High levels of the consultative resources and capacity needed to provide functional assessment leading to strategic and intensive instructional and intervention services, supports, strategies, and programs to academically and behaviorally underachieving, unresponsive, or unsuccessful students;

- High levels of parent and community outreach and involvement in areas and activities that support students’ academic and social, emotional, and behavioral learning, mastery, and proficiency; and, ultimately,

- High levels of student success that result in high school graduation and post-secondary school success.

_ _ _ _ _

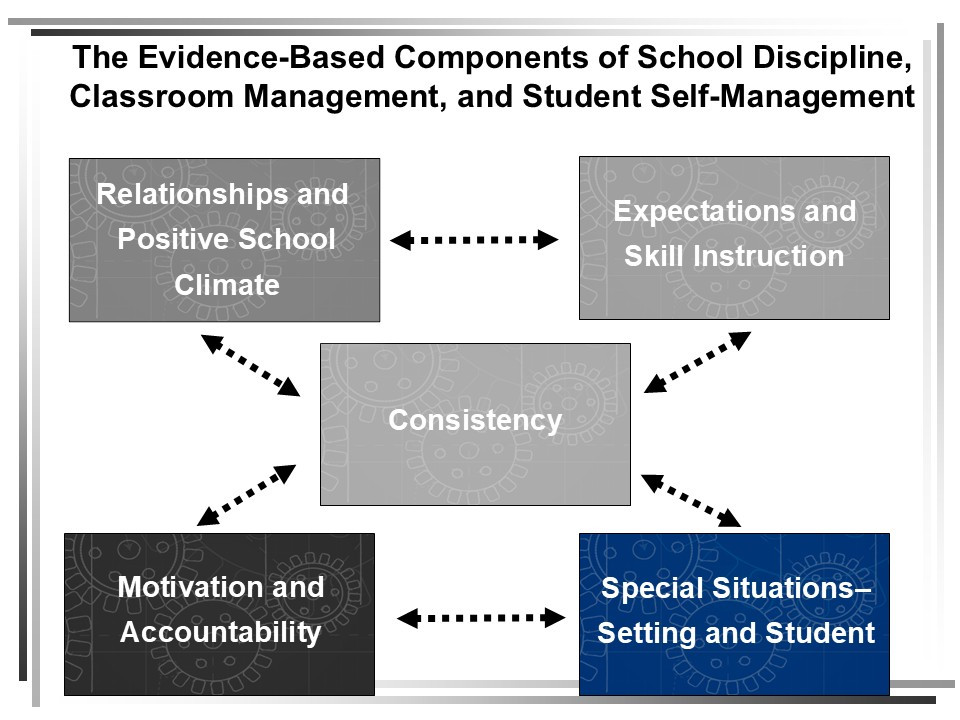

To accomplish these goals, research-to-practice studies have identified five critical interdependent components (see the Figure 1 below).

- Positive School and Classroom Climate, and Staff and Peer Relationships;

- Explicit Prosocial Behavioral Expectations in the classrooms and common school areas and Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Skill Instruction;

- Student Motivation and Accountability

- Consistency and Fidelity relative to the implementation of all of the above components; and

- Special Situations and the multi-tiered Application of the above to all school settings, all peer interactions (including those that prevent teasing, taunting, bullying, harassment, hazing, and physical aggression), and other special personal and life situations and events that impact students on an individual level

These are the “macrosystem” characteristics that schools need to evaluate right now as part of a needs assessment. The assessment results should lead to the Action Plans that will guide them later this summer and into the new school year (and beyond).

The oversight of these components typically is the responsibility of the School Discipline Committee (or the equivalent) which is comprised of teacher representatives from every grade level, as well as others from the different instructional support groups in the school, related services and special education professionals, the administration, and selected others.

Figure 1.

_ _ _ _ _

Component 1: Positive School and Classroom Climate, and Staff and Peer Relationships

Those who have lived in or experienced a toxic environment—at home, in the workplace, at school—understand the impact of climate on learning, behavior, attitudes, social interactions, and mental health. Many times, toxic or even negative environments exist because of the relationships within them.

Effective schools work consciously, planfully, and on an on-going basis to develop, reinforce, and sustain positive and productive across-school and within-classroom climates, relationships, and interactions for all students and staff. The policies, practices, and actions that establish and sustain these climates are inclusive. . . indeed, they are mindful of gender and gender identity, race and culture, socio-economic status and where students live in the community, family history and status.

Ultimately, assessments of the relationships in a school focus on interactions between students and students, students and staff, staff and staff, students and parents, and staff and students to parents, respectively.

Functionally, relationship-building involves time, training, commitment, experiences, coaching, evaluation, feedback, and practice. Students need to learn the social and interactional skills that establish positive relationships with others, and the different peer groups across the school need to “buy into” the process.

Concurrently, teachers need to recognize the importance of committing to effective communication and interactions with students, and collaboration and consultation with colleagues.

The strongest research-backed variables that schools should evaluate when assessing school climate and the relationships between staff and students include the following:

- Mutual Respect, Value, Trust, and Social Connectedness

- Physical and Emotional Safety, Support, and Availability

- Communication, Collaboration, Feedback, and Responsiveness

- Classroom Management, Instructional Competence, Fairness, and Equity

- Student Voice, Engagement, Belonging, and Autonomy

- Cultural and Student Diversity Awareness and Responsiveness

_ _ _ _ _

Given the discussion above, here are eight questions that School Leaders can use now to evaluate their current status in this component, and what they need to do to close specific gaps.

- Are we intentionally and consistently building and maintaining a positive, inclusive school climate that supports learning, behavior, and positive mental health for all students and staff? (Focus: schoolwide intentionality and consistency)

- Do our policies and daily practices reflect cultural responsiveness and sensitivity to gender identity, race, socioeconomic status, and family backgrounds? (Focus: equity and inclusion)

- Are we regularly assessing and strengthening the quality of relationships across all key groups—student-student, student-staff, staff-staff, staff-family, and student-family? (Focus: relational quality and stakeholder coverage)

- Do students receive explicit instruction and ongoing opportunities to learn and practice the social and relational skills needed to build and maintain healthy peer and adult relationships? (Focus: student skills instruction and transfer)

- Do teachers and staff have the training, time, and support to engage in effective communication, collaboration, and relationship-building with both students and colleagues? (Focus: staff capacity and professional development)

- Do students feel safe—physically and emotionally—and do they report feeling valued, respected, and connected to both peers and adults at school? (Focus: student perception and emotional safety)

- Are student voices genuinely included in school decision-making processes, classroom dialogue, and climate improvement efforts? (Focus: engagement, autonomy, and belonging)

- Are our staff evaluating their own communication, classroom management, and responsiveness practices to ensure they are fair, inclusive, and supportive of every student’s learning and social success? (Focus: reflection, fairness, and instructional equity)

Component 2: Explicit Prosocial Behavioral Expectations and Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Skills Instruction

All students—from preschool through high school—need to be systematically taught (just like an academic skill) the explicit social, emotional, and behavioral expectations in their classrooms and across the common areas of the school. These expectations need to be communicated in a positive, prosocial—rather than a negative, deficit-oriented—way. That is, students need to be taught “what to do,” rather than “what not to do.”

That is, teachers and administrators need to teach and prompt students, for example, (a) to walk down the hallway, rather than told being to not run; (b) to raise your hand with your mouth quiet and wait to be called on, rather than don’t blurt out answers; (c) to accept a consequence by controlling your emotions and following the directions to the consequence given, rather than don’t roll your eyes and give me attitude when I tell you to move your seat.

In addition, these expectations need to be behaviorally specific—that is, we need to describe exactly what specific, observable steps we want students to perform.

For example, I need you to:

- Walk onto the bus quietly, and keep some space between each student;

- Sit in the first open seat and move all the way in;

- Put your books on your lap or your bookbag under the seat in front of you;

- Talk only with your neighbors using a whisper or conversational voice; and

- Stay seated until the bus has stopped, and it is your turn to leave.

Critically, it is not instructionally helpful to initially talk to students (especially early elementary students) in constructs—for example, telling students that they need to be “Respectful, Responsible, Polite, Safe, and Trustworthy.”

This is because each of these constructs involves a wide range of implicit behaviors. At the elementary school level, students really do not functionally or behaviorally understand what these higher-ordered constructs are specifically requesting. At the secondary level, meanwhile, students often interpret these different constructs (and their implicit behaviors) very differently than staff.

Thus, if we want to teach students the interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional awareness, control, communication, and coping skills that that they need, we need to communicate explicitly and concretely so that different students at each grade and developmental level understand exactly what to do.

In addition, social skills need to be taught the same way that a successful basketball coach teaches the plays in his or her playbook. That is, we need to (a) teach students the specific steps for each social skill, along with the related behaviors; (b) positively demonstrate the steps to them in meaningful and real-life scenarios; (c) give students structured opportunities to practice each skill in simulated roleplays with guidance and explicit feedback; and then (d) help students to apply (or transfer) their new skills more automatically and independently to “real-world” situations.

Embedded also in this instruction should be the social problem-solving needed by students so that they learn how to evaluate and make the best behavioral choices for different situations.

Finally, students need to be taught (a) how to be aware of the different emotions that they experience in different situations; (b) how to maintain self-control when faced with emotional triggers and stress, peer pressure and conflict, or other home or school disruptions; (c) how to communicate their emotions as appropriate and needed to others; and (d) how to evaluate themselves after certain emotional events have occurred so that they can establish long-term coping skills and patterns.

Significantly, there are hundreds of important social, emotional, and behavioral skills that could be taught during students’ school careers. Examples of some needed social skills include: Listening, Following Directions, Asking for Help, Ignoring Distractions, Dealing with Teasing and Bullying, How to Accept a Consequence, How to Deal with Losing or Not Getting Your Own Way, How to Handle Peer Pressure and Rejection, How to be a Good Leaders and a Good Team Member, How to Set Goals and Develop Good Action Plans.

All of the core social skill instruction is led by general education teachers. This is because (a) they know the students better than anyone else; (b) they have more opportunities to prompt, practice, reinforce, and correct the skills in real-life classroom situations; (c) they need to use these skills to facilitate classroom management and positive school climates; and (d) they need to integrate these skills into students’ academic engagement and success.

For students who need modified, small group, or individual (cognitive behavior therapy-based) instruction (e.g., at the Tier 2 or Tier 3 levels), this is done by school or school-based mental health staff—counselors, psychologists, or social workers.

Significantly, this more intensive instruction typically is done to supplement the training that is also occurring in the classroom. This is because students need to hear the social skills language and prompts in their classrooms and across the common areas of the school. If this is missing, they will rarely transfer and apply the social skills training—on their own—from their mental health professional’s office into the different settings and situations that they actually experience on a day-to-day basis.

_ _ _ _ _

Given the discussion above, here are eight questions that School Leaders can use now to evaluate their current status in this component, and what they need to do to close specific gaps.

- Are our teachers explicitly teaching students what to do in specific behavioral terms, rather than what not to do, across both classroom and common school areas? (Focus: prosocial, positive phrasing and observable behaviors)

- Do we have clear, developmentally-appropriate, and behaviorally-specific expectations for students at each grade level, or are we relying too heavily on vague constructs like “respect” and “responsibility”? (Focus: clarity and student understanding of expectations)

- Are general education teachers regularly and systematically teaching core social, emotional, and behavioral skills as part of their classroom instruction? (Focus: classroom integration and teacher ownership)

- Are students given opportunities to observe, role-play, and practice key social skills (e.g., following directions, accepting consequences, handling peer pressure) with real-time feedback and coaching? (Focus: instructional process and skill acquisition)

- Do we ensure that Tier 2 and Tier 3 interventions provided by mental health staff reinforce and align with the classroom-based social skills instruction, promoting transfer across settings? (Focus: consistency and generalization of skills)

- Do teachers and staff provide consistent, in-the-moment prompts, reinforcement, and corrections of social-emotional skills during real-life school interactions? (Focus: application and reinforcement in natural contexts)

- Are our staff trained and supported to effectively teach, model, and reinforce social problem-solving, emotional regulation, and communication strategies for students at different developmental stages? (Focus: staff capacity and professional development)

- Do we have a system in place to monitor students’ progress in acquiring and using social, emotional, and behavioral skills over time? (Focus: assessment and continuous improvement)

Component 3: Student Motivation and Accountability

Even when students have mastered their social skills, they still need to be motivated to use them. And when the peer group (that says, “Be cool”) competes against teachers and other educators (who say, “Focus on school”), the importance of school-wide accountable approaches is apparent.

Accountability. School accountability processes consist of meaningful incentives and consequences that motivate students to use their prosocial skills, and someone (an adult, a peer, or the student him or herself) who consistently reinforces only appropriate behavior. These processes are important because (a) socially skilled students still need motivation to use their skills, (b) some students (called performance deficit students) lack this motivation, and (c) some students are more reinforced by the outcomes or the act of demonstrating an inappropriate (as opposed to an appropriate) behavior.

This school discipline component helps schools establish and implement grade-level and building-wide accountability systems that include progressively tiered and developmentally-appropriate and meaningful incentives and consequences that motivate and reinforce students’ appropriate interactions.

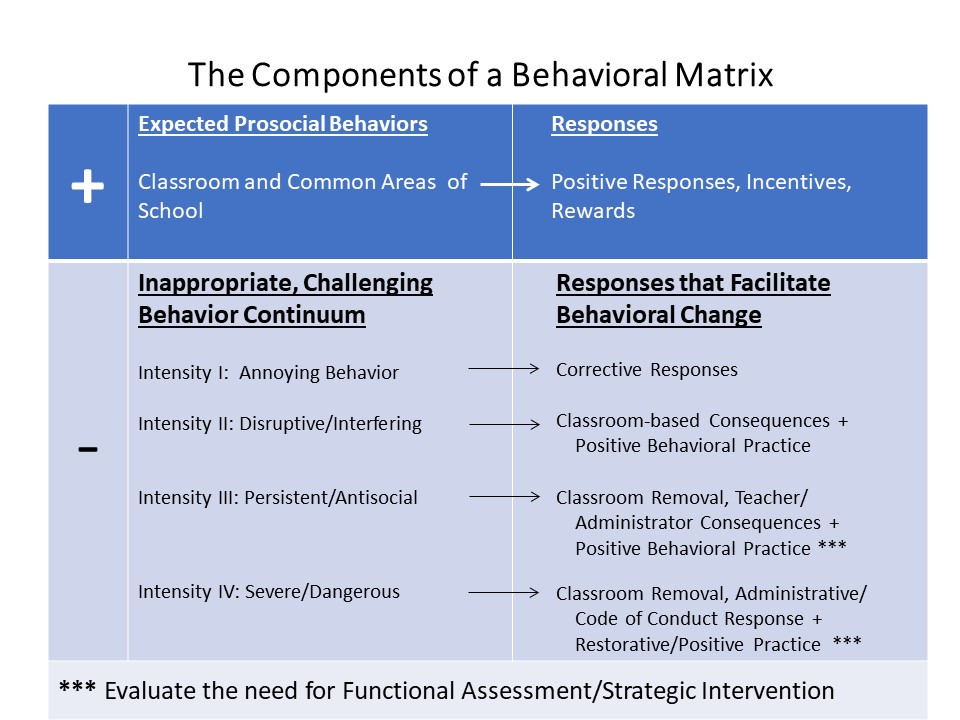

This is accomplished by creating, formalizing, and implementing a “Behavioral Matrix” that establishes a set of behavioral standards and expectations for all students. Created predominantly by staff and students, this matrix explicitly identifies, for all grade levels, behavioral expectations in the classroom and in other common areas of the school (connected with positive responses, incentives, and rewards), and different “intensities” levels of inappropriate student behavior (connected with negative responses, consequences, and interventions as needed; see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The four Intensity Levels are:

Intensity I (Annoying) Behavior. These are behaviors in the classroom that are annoying or that mildly interrupt classroom instruction or student attention and engagement. Teachers handle these behaviors with a minimum of interaction by using a corrective response (e.g., a non-verbal prompt or cue, physical proximity, a social skills prompt, reinforcing nearby students’ appropriate behavior).

_ _ _ _ _

Intensity II (Disruptive or Interfering) Behavior. These are behavior problems in the classroom that occur more frequently, for longer periods of time, or to the degree that they disrupt classroom instruction and/or interfere with student attention and engagement. Teachers handle these behaviors with a corrective response, and a classroom-based consequence (e.g., loss of student points or privileges, a classroom time-out, a note or call home, completion by the student of a behavior change plan).

After the consequence is over, and guided by the teacher, the student must positively practice the appropriate behavior that the student should have done and did not do (hence, requiring the consequence) at least three times as soon as possible.

_ _ _ _ _

Intensity III (Persistently Disruptive or Antisocial) Behavior. These are behavior problems in the classroom that significantly (as in a single incident) or persistently (as in multiple incidents that increase in severity over time) disrupt classroom instruction or engagement, or that involve antisocial acts toward adults or peers.

These inappropriate behaviors require some type of out-of-classroom response (e.g., a time-out in another teacher’s classroom, removal to a school “student accountability room,” an office discipline referral), and a consequence that involves the classroom teacher (even if, for example, an administrator is involved)—so that the student remains accountable to the teacher and the classroom where the behavior occurred.

The consequence could be followed by a restorative or restitutional pay-back (e.g., an apology, cleaning up/repairing damaged property or a messed-up classroom, community service), and should be followed by the positive practice of the appropriate behavior described in Intensity II above.

If it is believed or apparent that the inappropriate behavior is not a discipline problem but a social, emotional, behavioral, or psychoeducational problem, the student should be referred to the school’s Multi-Tiered Services (Child Study, Student Services) Team for assessments to determine the root cause(s) of the problem, and a resulting behavioral intervention plan that specifies the services, supports, strategies, or interventions that are both linked to the assessment results and needed to ameliorate the problem.

_ _ _ _ _

Intensity IV (Severe or Dangerous) Behavior. These involve extremely antisocial, damaging, and/or dangerous behaviors—on a physical, social, or emotional level— that are typically cited and described in a District’s Student Code of Conduct handbook. These inappropriate behaviors require an immediate administrative referral and response (e.g., a parent conference, suspension, or expulsion), followed (at times) by additional consequences, restitutional requirements, and (once again) positive practice sessions.

While an administrator may, by Code, need to suspend a student, if she or he believes that the offense is not a discipline problem but a social, emotional, or behavioral problem, the student—as in the Intensity III description above—should be referred into the school’s Multi-Tiered Services and Supports process.

_ _ _ _ _

Critically, because the behaviors at each intensity level are agreed upon by staff, and then taught and communicated to students, student behavior is evaluated against a set of explicit “standards” (rather than individually or capriciously by teachers or administrators). Thus, staff responses to both appropriate and inappropriate student behavior are more consistent and expected, and students know—in advance—what will occur for incidents of, for example, teasing through physical aggression. All of this facilitates an atmosphere that reinforces student responsibility and self-management.

Framed by the Behavioral Matrix as the primary school-wide accountability vehicle, a number of evidence-based strategies are evident in effective classrooms and schools:

- All students in the school experience five positive interactions (collectively, from adults, peers, or themselves) for every negative interaction;

- Students are largely motivated through positive, proactive, and incentive-oriented means;

- When consequences are necessary, the mildest possible consequence needed to motivate students’ appropriate behavior is used;

- Consequences (that motivate appropriate behavior), not punishments (that attempt to stop inappropriate behavior), are used;

- When consequences are over, students must still practice the previously-expected prosocial behavior at least three times under simulated conditions;

- Staff differentiate and respond strategically to skill-deficit versus performance-deficit students; and

- Staff recognize that incentives and consequences must remain stable because previous inconsistencies may have strengthened some students’ inappropriate behavior.

All students—at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels—typically are held accountable to the Behavioral Matrix. However, as students engage in Intensity III and IV behaviors, the need to link strategic or intensive interventions to analyses that determine the root causes of their ongoing or significantly inappropriate behavior becomes apparent. Moreover, when there are clear social, emotional, or mental health reasons for students’ significant behavioral challenges (see Component 5), the Behavioral Matrix (which focuses largely on students who are discipline problems) may give way to more psychologically-focused clinical interventions.

Motivation. On a functional level, both incentives and consequences result in positive and prosocial behavior (when students have learned and mastered these skills). Incentives motivate students toward the expected or desired behaviors, and consequences similarly motivate students toward expected or desired behaviors because they know that inappropriate behavior will result in the consequences actually being applied.

Critically, educators need to understand that they can only create motivating conditions. That is, they can’t force students to meet the behavioral expectations. Indeed, when we force students to do anything, we are managing their behavior, not facilitating self-management. And while adults need to do some management to teach and motivate students’ self-management, if they do not teach self-management skills (Component 2)—exclusively managing students’ behavior, they will never be able to socially, emotionally, or behaviorally manage their own behavior when, for example, adults are not present.

Beyond this, too often, school staff create “motivational programs” without involving the students and/or validating that the incentives and consequences they have chosen are actually meaningful and powerful to the students. Said a different way, schools do not want to “complete” this school discipline Component with incentives and consequences that look good “on paper,” but that are meaningless and that the students couldn’t care less about.

Thus, during the planning process, school staff need to engage and involve the peer group in designing the school’s motivational program. This is additionally important because it helps to avoid situations where specific peers—for example, on the playground, after school, on social media—are undermining the system by reinforcing others for demonstrating the inappropriate behaviors that the school staff is trying to decrease or eliminate. When students are committed to and motivated to make good choices in school—because they were involved designing the process—they are more likely to ignore or confront these peers. . . and do the right thing.

_ _ _ _ _

Given the discussion above, here are eight questions that School Leaders can use now to evaluate their current status in this component, and what they need to do to close specific gaps.

- Have we clearly defined, taught, and communicated schoolwide behavioral expectations and consequences through a shared Behavioral Matrix that is developmentally sensitive and consistently used across all classrooms in each grade level and across all common school areas? (Focus: structure, clarity, and consistency)

- Do our accountability systems differentiate between skill deficits (students who don’t know what to do) and performance deficits (students who know what to do but aren’t motivated to do it), and respond accordingly? (Focus: diagnostic understanding and targeted intervention)

- Are our staff trained and supported to respond to inappropriate behavior using the mildest necessary consequence—followed by opportunities for students to positively practice the expected behavior? (Focus: proportionality, learning, and follow-through)

- Do we maintain a consistent ratio of at least five positive interactions for every negative interaction that students experience from adults, peers, or themselves, and are these incentives developmentally appropriate and socially relevant to the diverse cultural, social, and emotional needs of our students? (Focus: positive reinforcement and school climate, motivational relevance and inclusion)

- Are students involved in co-designing motivational systems (e.g., incentives and accountability processes), and are those systems validated to ensure they are meaningful and effective to the students themselves? (Focus: student engagement and ownership)

- When a student exhibits serious or repeated behavioral challenges (Intensity III or IV), do we have a referral process to the Student Assistance Team (or the equivalent) that then identifies root causes and links the student to mental health, social-emotional, or behavioral supports as appropriate? (Focus: multi-tiered intervention and problem-solving)

- Are staff responses to student behavior consistent and aligned with agreed-upon standards, rather than being based on personal judgment or inconsistent application? (Focus: equity, fairness, and schoolwide coherence)

- Are restorative or restitutional practices (e.g., apologies, community service, repairing harm) used intentionally and appropriately as part of the consequence process to build responsibility and relationships? (Focus: restorative justice and behavioral ownership)

Component 4: Consistency and Fidelity

Consistency is an essential process in a school discipline initiative relative to facilitating students’ social, emotional, and behavioral self-management. It can’t be downloaded into a person’s behavioral repertoire—like a software program on a computer, and it can’t be included in staff member’s annual flu shot.

Instead, consistency develops, experientially, in every student and staff member in a school over time and, even then, it needs to be consciously maintained in an ongoing way.

Consistency is “grown” through effective strategic planning with detailed implementation plans, good communication and collaboration, sound implementation and evaluation, and consensus-building coupled with constructive feedback and change.

It’s not easy. . . but it is necessary for school success. And functionally, it must occur across all three of the school discipline Components discussed thus far.

More specifically, in order to be successful, staff (and students) need to (a) demonstrate consistent prosocial relationships and interactions—resulting in consistently positive and productive school and classroom environments (Component 1); (b) communicate and maintain consistent behavioral expectations, while consistently teaching and practicing them (Component 2); (c) use consistent incentives and consequences, while holding student consistently accountable for their appropriate behavior (Component 3); and then (d) apply all of these components consistently across all of the settings, circumstances, and peer groups in the school (see the upcoming Component 5).

Moreover, consistency occurs when staff interact similarly (a) with the same individual students, (b) across different students, and (c) within their grade levels or instructional groups... (d) across time, (e) across settings, and (f) across situations and circumstances.

Critically, when staff are inconsistent, students feel that they are being treated unfairly or that other students are being treated preferentially. As a result, they sometimes (a) behave differently for different staff or in different settings, (b) they can become manipulative—pitting one staff person against another, and (c) they often emotionally react—with some students getting angry with the inconsistency and others simply withdrawing because they feel powerless to change it.

Said a different way: Inconsistency undercuts student motivation and accountability, and you don’t get the social, emotional, or behavioral interactions that you want from individual students, groups of students, or entire grade levels of students. . . in the classroom or in the common areas of the school.

Relative to Fidelity, a district or school may develop a multi-tiered School Discipline Action Plan that is sound and well-organized, specific and well-designed, research-based with proven practices, and well-staff and resourced. And yet, if there is no, poor, or inconsistent training, or if staff are not held accountable for implementation and results, the Plan may be implemented incompletely or improperly.

That is, a lack of implementation fidelity will undermine and eventually doom any initiative—no matter how well-designed the Action Plan or how well-resourced its activities are.

_ _ _ _ _

Given the discussion above, here are eight questions that School Leaders can use now to evaluate their current status in this component, and what they need to do to close specific gaps.

- Are staff consistently implementing all key components of our school discipline approach—positive climate and relationships, behavioral expectations and instruction, and accountability systems—across all classrooms and common areas? (Focus: systemwide application of Components 1–3)

- Do students experience consistency in how different staff members respond to the same behaviors, both within and across grade levels, settings, and circumstances? (Focus: fairness, trust, and predictability from the student’s perspective)

- Are we monitoring and supporting staff to ensure that behavioral expectations are taught, practiced, reinforced, and corrected consistently over time—not just at the beginning of the year or during crises? (Focus: sustained implementation, not episodic)

- Do we have procedures in place to ensure that incentives and consequences are applied equitably and consistently for all students, regardless of who they are or which adult is supervising? (Focus: discipline equity and reliability)

- Have we built systems for feedback, reflection, and collaboration that allow staff to address inconsistencies in implementation, clarify expectations, and adjust practices as needed? (Focus: communication, learning culture, and shared responsibility)

- Is there a shared understanding among staff about what fidelity of implementation looks like for our school discipline plan, and are there tools or processes to assess and support it? (Focus: clarity, accountability, and support)

- Do we offer ongoing training, coaching, or check-ins to help staff build and maintain consistency and fidelity in their daily behavioral practices? (Focus: professional development and capacity building)

- Are we tracking whether inconsistencies in staff practices are contributing to student disengagement, behavioral issues, or perceptions of unfair treatment—and addressing these patterns proactively? (Focus: root-cause analysis and student outcomes)

Component 5: Special Situations and Multi-Tiered Services and Supports

The last of the five evidence-based, interdependent school discipline components involves three “Special Situations”—the last of which requires a sound district and school multi-tiered system of supports.

The first Special Situation focuses on the multiple settings in a school. Here, schools need to plan for student behavior and interactions not just in the classroom, but also in all of the common areas of the school—for example, the hallways, bathrooms, buses, cafeteria, and the playgrounds or common gathering areas.

It is important to understand that these common school areas are psychosocially more complex and dynamic than a classroom setting. Indeed, in these common school settings, there are typically more multi-aged or cross-grade students, more and more varied social interactions, more physical space or fewer explicit boundaries, fewer staff and supervisors, and different social (especially, peer) demands. Thus, students’ positive social, emotional, and behavioral classroom interactions are more complex, and can be more taxed in the common school areas.

Accordingly, all students need to be taught how to adapt and apply their interpersonal, social problem solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional awareness, control, communication, and coping skills in each common school area. Moreover, the training needs to be tailored to the social demands and expectations of these settings.

At the same time, staff who are supervising in these settings also need to be trained and coached to make sure that they are fairly and consistently (a) evaluating students’ behavior relative to the explicit expectations established for each setting; (b) prompting and reinforcing appropriate student behavior; and (c) responding to inappropriate behavior when exhibited by different-aged students from varied gender, racial, socioeconomic, and other backgrounds.

_ _ _ _ _

The second Special Situation focuses on the impact of peer groups as psychosocial influencers, and their relationship to teasing, taunting, bullying, harassment, hazing, and physical aggression (fighting).

As alluded to in the Component 1 through 3 discussions above, it is important to understand that the peer group is often a more dominant social and emotional “force”—relative to motivating or reinforcing individual students’ behavior—than the adults in a school.

As such, the school’s approaches to student behavior and self-management in the first four components must be consciously generalized and applied—relative to climate, relationships, behavioral expectations, skill instruction, motivation, and accountability—to ensure that the different peer groups in a school act as active positive and prosocial behavioral models on behalf of all students in the school.

Realistically, however, many schools have some small (or large) pockets of teasing, taunting, bullying, harassment, hazing, and physical aggression (fighting). Thus, this Component collectively applies the first four components by consistently teaching and motivating students to use the interpersonal, social problem solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional awareness, control, communication, and coping skills directly related to the prevention and early response to these situations and acts. It also teaches students who are bystanders to these events how to effectively respond when they occur.

When these student response strategies work, students know how to respond to peer-instigated teasing, rejection, accusations, and social pressure when they occur. Moreover, because all of the students are trained in these strategies, this additionally prevents some of the negative peer interactions from ever occurring—because the potentially “aggressing or antisocial” peer group knows that their “targets or victims, or the student bystanders” are prepared to respond appropriately and courageously to them.

Finally, all of this also prevents the students—who are being socially targeted or victimized—from responding or retaliating inappropriately, thus becoming part of a broader and more complex disciplinary situation.

In closing, these first two Special Situations overlap. This is because most peer-to-peer teasing, taunting, bullying, harassment, hazing, and physical aggression occurs in the common areas of the school. Clearly, the most important focus of a school discipline initiative is social, emotional, and behavioral self-management. In this Component, the focus is on teaching, motivating, and reinforcing the different peer groups in a school so that they are—especially at the secondary level—consistently prosocial contributors to the positive and safe culture, climate, norms, and interactions across the student body.

However, when students persist in these inappropriate and antisocial behaviors, the next part of this Special Situation—multi-tiered service and supports may come into play.

_ _ _ _ _

The third Special Situation focuses on the fact that some misbehavior occurs due to some students’ significant or intense personal histories, situations, or circumstances that are not disciplinary in nature. Indeed, these social, emotional, behavioral, or mental health issues are the root causes of the inappropriate behavior.

Examples of some of the triggers or causes of these social, emotional, and/or behavioral (not disciplinary) challenges include:

- Physical, Biological, Physiological, Genetic, Neurological issues

- Mental health issues

- Disabilities

- Significant stresses or traumas

- Dysfunctional home and family situations

- Poverty or Economic stresses

- Drugs, Alcohol, Vaping

- Significant Life Changes or Events

Critically, when these students misbehave, disciplinary actions are unlikely to decrease or eliminate the underlying problems. What is needed instead are multi-tiered strategic (Tier 2) or intensive (Tier 3) services, supports, strategies, or interventions that are (a) guided by the school’s Multi-Tiered Services or Student Support Team, and (b) based on functional or diagnostic assessments that determine which root causes need intervention attention.

For this Special Situation, then, it is important that teachers, support staff, and administrators learn, understand, and discriminate between “discipline” problem students and students with social, emotional, behavioral, or mental health problems. While we are not saying that the latter group of students should not be sent to the principal’s office and/or suspended from school (even the first time) after demonstrating Intensity III or IV infractions. . . we are saying that administrators should simultaneously consider whether a Student Support Team assessment is needed.

Said a different way: When students’ challenges are due to social, emotional, behavioral, or mental health root causes, an office referral or an in- or out-of-school suspension will not act to “motivate” most students to change—even though it may be administratively necessary. For students with social, emotional, or behavioral problems, the only way to decrease or eliminate their challenges and future misbehavior is through strategic or intensive social, emotional, behavioral, or mental health services, supports, strategies, or interventions.

_ _ _ _ _

Given the entire Special Situation discussion above, here are eight questions that School Leaders can use now to evaluate their current status in this component, and what they need to do to close specific gaps.

- Have we explicitly defined behavioral expectations—and taught social, emotional, and behavioral skills—for all common school settings (e.g., hallways, cafeteria, buses, playground), accounting for the unique social demands of these spaces, respectively? (Focus: proactive preparation for diverse, dynamic environments)

- Are the adults supervising common school areas trained to fairly and consistently prompt, reinforce, and respond to individual student and peer group behavior across different ages, cultures, and other backgrounds? (Focus: staff preparedness and equity in common areas)

- Do we address peer influence intentionally by equipping students to respond to teasing, bullying, or peer pressure, and by cultivating peer groups as positive and prosocial models across the school? (Focus: peer culture, prevention, and empowerment)

- Are students taught specific conflict prevention and resolution strategies when they are bystanders who are witnessing bullying, harassment, or other aggressive behaviors? (Focus: student agency and prosocial norms)

- Do we have a MTSS system in place to identify students whose behaviors may be driven by underlying social, emotional, behavioral, or mental health needs so that disciplinary actions occur accordingly, and these students receive appropriate tiered services and supports? (Focus: MTSS alignment and proper problem identification)

- Do our staff understand how to distinguish between willful misconduct and behavior rooted in trauma, disability, mental health, or socio-environmental factors— and are they trained in appropriate response pathways for each? (Focus: educator awareness and response differentiation)

- Are we using functional assessments or root-cause analyses to guide Tier 2 and Tier 3 supports, ensuring interventions are linked to the reasons behind a student’s behavior—not just determined by the behavior itself? (Focus: data-informed intervention and precision support)

- Do we monitor whether our disciplinary practices—such as referrals and suspensions—are effective for individual students, are not disproportionately given to students of color or with disabilities, and whether these disciplinary actions need to change and/or focus more on therapeutic or strategic support services instead? (Focus: effectiveness of discipline vs. need for mental health intervention)

Additional Characteristics of Effective School Discipline Systems at the Grade and Classroom Levels

As discussed above, the five interdependent components of an effective school discipline, classroom engagement and behavior management, and student self-management system anchor how administrators, classroom teachers, related services and support staff, and others should systemically approach students’ (and staff) social, emotional, and behavioral interactions in a school.

Moving from a systems perspective to a group or team perspective, a critical behavior management principle is:

“The Grade or Instructional Team level is the Least Common Denominator in a School.”

That is, in order to best maintain the consistency and fidelity of the special situation, behavioral accountability and motivation, social skill expectations and instruction, and climate and relationship initiatives above, everyone in the same grade, instructional, or departmental team must “pull in the same direction.”

Said a different way: When staff members—innocently, inadvertently, or deliberately. . . due, for example, to suspect training or skills, ego or choice, indifference or disrespect—behave or interact in ways counter to agreed-upon actions or activities in their school in each of the five components above, they directly or indirectly undermine the discipline system and its structure, and they introduce loopholes that weaken students’ social, emotional, and behavioral learning and accountability.

Given this, let’s discuss what individual classroom teachers should be doing—relative to classroom engagement and behavior management. . . with an understanding that all teachers at the same grade, department, or instructional level are doing the same.

This discussion will emphasize the importance of the following skill areas:

- Clear Expectations and Structured Routines

- Active Supervision and Monitoring

- Positive Reinforcement and Feedback

- Respectful and Corrective Discipline

- Student Self-Management and Responsibility

- Respectful Relationships and Interactions

- Engaging Instruction and Active Participation

- Safe, Organized, and Responsive Environments

_ _ _ _ _

Effective teachers demonstrate essential classroom engagement and behavior management characteristics in their classrooms every day. These are the characteristics that School Leaders can use to evaluate their current staff now—during the early summer—to determine their strengths, weaknesses, gaps, and opportunities in preparation for the new school year.

Authority, Cooperation, and the Classroom Environment

When we think about the best teachers we’ve seen, it's easy to assume that their success comes from personality—charm, charisma, or a natural ability to connect with kids. But research—and what we see in successful classrooms every day—tells a different story. Effective classroom management and strong student-teacher relationships aren’t about personality. They’re about practice.

The most effective teachers consistently establish appropriate levels of authority and cooperation. These two pillars create a structured yet supportive learning environment where students thrive academically, behaviorally, and socially.

Establishing Accountability Through Clarity, Consistency, and Compassion

Accountability to teachers in the classroom doesn’t require dominance and unilateral control. It requires leadership. Effective teachers create environments where expectations are clear, rules are fair, routines are established, and students know exactly what success looks like.

First, these teachers clearly define classroom expectations and consequences, and then they teach them—just like their academic skills. From Day One—and reinforced frequently thereafter—they also establish routines for transitions, group work, material use, and classroom entry and exit.

Expectations are stated in positive, behaviorally-specific terms, they are posted visibly, and they revisited and reinforced often. Most importantly, expectations are modeled and taught, not just stated and demanded. When students meet classroom expectations, effective teachers acknowledge it regularly through verbal praise, nonverbal cues, or tangible incentives. When students don’t, consequences are applied calmly, fairly, and predictably, and positive-practice opportunities follow.

Effective teachers demonstrate firm, but caring, behavior. They use steady, calm voices—even when correcting misbehavior—and they know when to ignore minor distractions while reinforcing others who are on task. These teachers also use low-level, unobtrusive strategies to manage misbehavior, such as moving closer to students who are off-task, using non-verbal cues like a raised hand, or redirecting behavior without calling attention to specific students.

Teacher responses escalate only as needed, and student dignity is always maintained. Effective teachers never resort to sarcasm, yelling, or punitive threats. They focus on changing inappropriate behavior—not on labeling or personally criticizing students.

Finally, effective teachers use effective instruction to anchor their classroom management. They establish meaningful lessons with goals that are developmentally appropriate, realistic, engaging, differentiated, and scaffolded. Students know what they’re working toward and how to measure their progress and success.

Cultivating Cooperation Through Relationships and Inclusion

But accountability is also earned through empathy and connection. As noted above, students are far more likely to engage in learning, behave appropriately, and meet expectations when they feel their teacher cares about them as individuals.

Effective teachers make it a priority to take a personal interest in students. They greet students at the door, call them by name, and learn about their lives outside the classroom. These small, but important, interactions build rapport and signal that every student matters.

In the classroom, cooperation is reinforced through equitable and positive interactions. Effective teachers make regular eye contact with all students, move freely around the room to maintain proximity, liberally reinforce students for their contributions and good behavior, and give students leadership opportunities that build ownership.

Effective teachers also give students time to think and respond, and they ensure that quieter or less confident students have equal opportunities to speak. Rather than rushing to the first raised hand, they pause, allowing all learners—regardless of ability—to contribute meaningfully. This patience shows respect and encourages participation.

When teachers demonstrate the characteristics and skills above, misbehavior is the exception—not the norm—because students are engaged, respected, and supported. In the end, classroom management isn’t about control—it’s about cultivating the right conditions so students can manage themselves. When accountability and cooperation are in balance, teachers spend less time managing behavior, and more time focused on student learning.

Given the discussion above, here are eight areas that School Leaders can use now to evaluate their classroom teachers’ and grade or instructional teams’ current classroom engagement and behavior management skills and status, and what they need to do to close specific gaps as the new school year begins.

- Clear Expectations and Structured Routines

Teachers clearly state their behavioral expectations when introducing new tasks or classroom activities.

Students understand what's expected and can articulate classroom rules and procedures.

Daily routines are predictable, allowing students to focus more on learning and less on guessing what comes next.

_ _ _ _ _

- Active Supervision and Monitoring

Teachers consistently monitor student behavior and engagement, whether students are listening to a lecture, working in groups, or completing independent tasks.

When students begin to get off-task, effective teachers notice early and redirect behavior quickly and calmly, preventing escalation.

_ _ _ _ _

- Positive Reinforcement and Feedback

Effective teachers provide frequent specific praise and reinforcement for appropriate behavior—aiming for five positive interactions for every one corrective interaction.

They highlight students’ efforts, reinforce growth, and create a culture where doing the right thing is noticed and valued.

_ _ _ _ _

- Respectful and Corrective Discipline

When misbehavior occurs, teachers respond with measured, respectful, and appropriate consequences.

Mild misbehaviors are addressed with simple prompts or cues; more serious behaviors involve clear, fair consequences, followed by opportunities to practice appropriate behavior.

Discipline is consistent, not arbitrary, and students know the “why” behind the consequence.

_ _ _ _ _

- Student Self-Management and Responsibility

Effective teachers teach students how to reflect on their behavior, use self-calming and self-control strategies, and take responsibility for their actions.

Classrooms are learning laboratories for social-emotional skills—like how to manage frustration, resist distractions, and navigate peer conflict.

_ _ _ _ _

- Respectful Relationships and Interactions

Teachers consistently treat students with dignity and respect, modeling calm, courteous behavior.

Students are given space, are listened to without interruption, and know their voices matter.

Respect is mutual—students also treat teachers and classmates with kindness and consideration.

_ _ _ _ _

- Engaging Instruction and Active Participation

Lessons are designed to keep students attentive, motivated, and academically engaged.

Learning tasks are meaningful and varied, allowing students to work individually, with partners, or in small groups.

Students show enthusiasm for learning because they know their success is supported and celebrated.

_ _ _ _ _

- Safe, Organized, and Responsive Environments

Classrooms are physically safe, clean, and accessible, with clear pathways, posted emergency procedures, and materials in good repair.

The environment reflects a sense of order and readiness for learning.

How Related Services and Support Staff Contribute to Effective School Discipline Systems

In today’s classrooms, educators face more social, emotional, and behavioral challenges than ever before. As such, sound evidence-based blueprints, teacher teams, and teachers are still not enough for complete discipline and behavior management success. Thus, schools must be fully committed to providing students with multi-tiered services, supports, and/or interventions when needed. This involves multidisciplinary intervention specialists like counselors, school psychologists, social workers, special education teachers, and other related services professionals.

In order to deliver more strategic and intensive behavioral and mental health services, these professionals need to blend direct intervention and therapeutic services to the students with indirect, consultative services to teachers and other colleagues. This blend ensures that the time that challenging students spend directly with the related services professionals—for example, individually or in small groups outside of the classroom—will transfer or generalize when these same students are in their classrooms, the common areas of the school, and with their peers.

Ultimately, to be successful, related services professionals consistently demonstrate seven key areas of skills and interactions.

- Clear Communication and Empathy

- Patience, Flexibility, and Creativity

- Leadership, Consultation, and Collaboration

- Culturally Responsive and Trauma-Informed Practice

- Data-Driven Problem Solving

- Expertise in Evidence-Based Interventions

- Ongoing Support and Follow-Through

These are briefly described below.

Clear Communication and Empathy

Effective related services professionals listen first, and then respond clearly and empathetically. They show genuine empathy for both teachers and students, helping to build trust, rapport, motivation, and a commitment to change. Warm, straightforward language ensures that teachers feel understood and supported, and students feel heard.

These professionals strategically frame their communication—for example, by avoiding technical jargon—so everyone feels that their lived experiences are respected, and that they are on the same page. Culturally responsive communication is an essential part of this skill set as specialists adapt their approaches and styles to students’ and families’ backgrounds, knowing that cultural sensitivity builds trust and enables them to connect meaningfully. By showing cultural respect, these professionals—once again—increase students’ and teachers’ to engagement in the change process.

_ _ _ _ _

Patience, Flexibility, and Creativity

Because students needing strategic (Tier 2) or intensive (Tier 3) social, emotional, or behavioral interventions demonstrate either significant and intense or frequent and persistent challenges, the change process requires time and patience. These qualities are consistently demonstrated by effective related services professionals, and this helps to model and encourage the same qualities in teachers, other staff, and involved students.

Effective intervention specialists also understand that—while their approaches need to be evidence-based and proven (see below)—they need to be flexibly implemented and creatively modified to fit distinct and sometimes unique conditions and situations. Said a different way, while interventions here should be based on sound functional and/or diagnostic assessments, even high probability of success interventions do not always succeed. This is especially true as school personnel do not have perfect control over all of the internal and external student-specific and ecological variables at play.

Thus, these professionals handle setbacks calmly. If a plan needs revision, they view this as part of the process, rather than another setback or failure. This, once again, models a “never-give-up” perspective that helps teachers and students believe that we will never give up on our most behaviorally challenging students and situations.

_ _ _ _ _

Leadership, Consultation, and Collaboration

Beyond working one-on-one with individual students demonstrating social, emotional, or behavioral challenges, effective related services professionals demonstrate sound leadership, consultation, and collaboration skills. Critically, leadership here is not about titles—it’s about relationships, problem-solving, practical strategies, and the support that teachers need so that they are confident in and competent with supporting and implementing interventions in their classrooms and monitoring student progress.

Relative to consultation, intervention specialists observe the ecology and dynamic interactions within teachers’ individual classrooms, and they engage in ongoing conversations so that they understand how different teachers integrate the five school discipline components discussed earlier in this Blog in their respective classrooms. This helps these specialists to adapt needed strategies to specific teacher practices and classroom contexts, build understanding and trust, and encourage teachers to try new approaches—for example, behavioral support plans, self-regulation strategies, or changes in classroom routines that boost student engagement.

Collaboration is the glue that holds all of these efforts together. Effective related services professionals work side-by-side with teachers, administrators, students, and their families during meetings, planning sessions, classroom push-ins, and follow-up evaluations—creating a shared understanding of the intervention goals, design, and expected outcomes. When everyone is working together, using common language and reinforcing the same skills, commitment is maximized as is the potential for intervention success.

_ _ _ _ _

Culturally Responsive and Trauma-Informed Practice

Today’s students come from diverse backgrounds, and many have experienced significant stress, anxiety, or trauma in their lives. Effective mental health professionals are sensitive to these realities, help the teachers they consult with understand these realities, and adjust their interventions accordingly. They recognize that a student’s behavior may be linked to cultural norms or past stressors, and not to just willful misbehavior. By acknowledging this, they strengthen the quality of their support, and their opportunities for success.

As one expert put it, “Culturally responsive staff who show an understanding of students’ backgrounds build trust and connect deeply.”

Stress- and trauma-informed approaches use strategies that help students feel safe—in the classroom, the common areas of the school, and when working with intervention specialists. At the therapeutic level, these approaches (see below) typically incorporate cognitive-behavioral techniques when students are dealing with high levels of anxiety or trauma, and the cues or prompts for these strategies are shared with classroom teachers who learn—hand-in-hand with the students—how and when to use them.

In all, effective behavioral intervention professionals tailor their help to each student’s story, cross-train their students with their teachers when appropriate, and focus on students’ interpersonal, social problems solving, conflict prevention and intervention, and emotional awareness, control, communication, and coping goals.

_ _ _ _ _

Data-Driven Problem Solving

Effective related services professionals consistently use a data-driven problem solving approach in all of their services. This approach applies four specific steps: Problem Identification and Discrimination; Functional or Root Cause Problem Analysis; Intervention Design and Implementation; and Progress Monitoring and Evaluation.

In fact, this process should be consistently used at all levels of a school’s Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) and, hence, it should be used at the Tier 1 level by classroom teachers. . . supported and reinforced by the related services professionals.

Data-driven problem solving ensures that teachers and intervention specialists are not implementing services, supports, or interventions before understanding and validating the underlying root causes of a specific problem. Significantly, this process is not meant to delay interventions; it is meant to ensure that high probability of success interventions are implemented the first time.

Effective related services professionals understand that most students’ behavioral challenges are complex and multi-layered, and that a multi-disciplinary team of colleagues is often needed. This reinforces the interdependence of the seven key areas of skills and interactions that we are now discussing, and why the problem solving process is so greatly needed as a guide.

_ _ _ _ _

Expertise in Evidence-Based Interventions

Top related services professionals possess deep knowledge and skills in proven, evidence-based strategies and interventions for improving student behavior and social interactions. Critically, they connect these approaches to functional and ecologically-based assessments, and they know which ones match the prevailing conditions relevant to specific situations.

Collectively, all schools should have access to a cadre of related services staff who are skilled in implementing and consulting with instructional staff effective across a wide range of strategic and intensive interventions. These approaches include:

- Positive Reinforcement Strategies and Schedules

- Extinction or Planned Ignoring

- Stimulus Control/Cueing

- Behavioral Task Analysis and Backward Chaining

- Response Cost and Bonus Response Cost Interventions

- Peer/Adult Mentoring and Mediation

- Educative Time-Out

- Social Skills Instruction

- Emotional Self-Regulation or Self-Control Training

- Response Cost Interventions

- Positive Practice and Restitutional Overcorrection

- Independent, Dependent, and Interdependent Group Contingencies

- Behavioral Contracting

- Self-Talk and Attribution (Re)Training

- Cognitive Thought Stopping

- Self-Management, Self-Monitoring, and Self-Reinforcement Strategies

- Progressive Muscle Relaxation Techniques

- Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions/Therapies

- Systematic Desensitization

- Emotional/Anger Control and Replacement Therapies

- Stress and Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapies

_ _ _ _ _

Ongoing Support and Follow-Through

Effective related services professionals understand that “being there for the long haul” is a necessity for successful services. Many schools and staff “run a marathon” with their behaviorally challenging students from preschool through high school. Given this, intervention specialists are adept at using their multi-disciplinary team and colleagues as a layered support system that follows students, as needed, from year to year and school to school.

At a more microcosmic level, when a behavioral intervention plan is implemented this is (as discussed above) only one step in the Problem Solving process. What makes the plan successful is the ongoing support and follow-through from the related services professionals tied to the plan—ensuring that interventions are implemented with fidelity (or integrity), that there are short-term and long-term efficacy evaluations, and that there is formal and informal follow-through.

While many interventions for behaviorally challenging students are implemented in their classrooms, effective related services professionals know that they are active members of the intervention team, and teachers do not do “it” alone. These professionals regularly check in, adjust strategies, and celebrate small wins. They understand that new patterns take time to build, and that encouragement is essential. They make themselves accessible when things go sideways, and show up not just when things are calm, but when support is needed the most.

_ _ _ _ _

Given the entire discussion above, here are eight questions that School Leaders can use now to evaluate the current status of their related services professionals as related to school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management. Tacitly, this can also help evaluate the expertise available to School Leaders’ multi-tiered system of supports. . . relative to strengths, weaknesses, gaps, and needed directions later this summer and into the new school year.

- To what extent are our counselors, psychologists, social workers, and other related services professionals providing a deliberate blend of direct student interventions and indirect consultative support to teachers?

How is this structure ensuring that social, emotional, and behavioral skills taught in individual/small group sessions are explicitly generalized and supported within the general classroom and school environment?

_ _ _ _ _

- How effectively do our related services professionals demonstrate clear, empathetic, and culturally responsive communication when interacting with both students/teachers/families?

What specific evidence exists (e.g., feedback, observation) that they actively listen, build trust/rapport, avoid jargon, respect lived experiences, and adapt communication to diverse backgrounds to foster engagement in the change process?

_ _ _ _ _

- Do our intervention specialists consistently demonstrate and model patience and a "never-give-up" attitude when faced with setbacks or when evidence-based interventions need modification?

How do they approach and communicate necessary revisions to behavioral plans, framing them as part of the process rather than failures?

_ _ _ _ _

- How effectively are our related services professionals functioning as consultants and collaborators (demonstrating leadership through relationships and support) rather than top-down experts?

Specifically, how do they observe classroom ecologies, understand unique teacher practices/discipline integration, adapt strategies contextually, build trust, and encourage teachers to implement new approaches (e.g., BIPs, self-regulation strategies, routine changes)?

_ _ _ _ _

- How systematically do our mental health professionals incorporate culturally responsive and stress/trauma-informed principles into behavior assessment, intervention design, and staff consultation?

What evidence exists that they help teachers understand how behavior might link to cultural norms or past stress/trauma (not just willfulness), and that cross-training occurs so teachers can support therapeutic strategies

_ _ _ _ _

- To what extent is the four-step data-driven problem-solving process (Problem Identification/Discrimination, Functional/Root Cause Analysis, Intervention Design/Implementation, Progress Monitoring/Evaluation) consistently applied by our related services staff across all tiers (including supporting Tier 1)?

How does this process ensure root causes are validated before high-probability-of-success interventions are implemented—thereby preventing low-probability-of-success efforts?

_ _ _ _ _

- How do we ensure our related services staff possess and effectively apply deep expertise in the wide range of evidence-based interventions listed (e.g., Positive Reinforcement Schedules, Social Skills Instruction, Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions, Trauma-Focused CBT, Self-Management Strategies, etc.)?

What mechanism exists to match these interventions specifically to functional/ecological assessments and the unique conditions of each student/situation?

_ _ _ _ _

- How robust are the systems for ongoing support, follow-through, and longitudinal tracking by our related services professionals?

Specifically, how do they ensure: (a) intervention fidelity/implementation integrity (e.g., observation, check-ins), (b) formal/informal efficacy evaluations at multiple time points (short and long-term), (c) regular adjustment of strategies based on data, (d) celebration of progress, and (e) active team membership to prevent teachers from feeling isolated in implementation?

How are supports coordinated across years and school transitions?

A Call to Action: Strategic Implementation for School Leaders

Our parting Call to Action, once again, asserts that the summer months offer districts and schools a "unique and invaluable opportunity for reflective analysis, strategic planning, and skill development."

All of our discussions about the components of effective school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management—along with the discussions and evaluation questions of how grade- and instructional teams, individual teachers, and related services professionals effective implement and fit into these components— provide school leaders with research-proven templates to use to evaluate the strengths, weaknesses, gaps, and needed changes for these groups to best prepare for the coming new school year.

After completing their assessments, the next critical challenge for administrators and other school leaders involves translating the findings into strategic actions that produce measurable improvements in school-wide discipline and behavior management systems.