How a Comprehensive Blueprint Prevents Isolated Solutions and Inconsistent Results

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

Well. . . “all of a sudden,” there has been a nationwide rush of policy, publication, media, and legal attention to students’ academic outcomes. . . in the area of reading. And interestingly, from a national and state proficiency perspective—at least as measured by tests like the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) and annual state standards/proficiency assessments, not much has changed.

And that, in fact, is the problem.

With all of the attention and billions of dollars invested over the past twenty years in improving student reading, student progress still is lacking. . . especially for students of color and students with disabilities.

And for all of the national reading “experts”—who have tried to address literacy at the curriculum and instruction levels, at the assessment to intervention levels, and at the student policy to practice levels—once again, progress is lacking.

And, I’m not blaming. . . I’m just exclaiming.

_ _ _ _ _

While there are many triggers to this “new” (actually, déjà vu) national focus on literacy instruction and student proficiency, let me mention a few.

- First: Last week, on February 20, 2020, as part of a legal settlement agreement, the state of California agreed to provide $53 million for early (Kindergarten to Grade 3) literacy instruction—and a range of services to support this—for 75 Los Angeles schools with the highest concentrations of 3rd grade students scoring at the lowest level on the state’s reading tests.

This court-approved amount settles a 2017 lawsuit that maintained that the Plaintiff’s constitutional rights by failing to teach them to read. The Plaintiffs were children from two schools in the Los Angeles area, and one child from Stockton. These children sued the California Board of Education, the State Education Department, and the State Superintendent for Education.

[CLICK HERE for Recent Education Week story]

If that did not get the attention of state departments of education across the country, I’m not sure what will.

_ _ _ _ _

- Second: Across the country, many states are realizing that their laws—requiring schools to retain students who are not reading at grade level at the end of Third Grade—are not resulting in substantially more students who are proficient in the different areas of reading.

Some of these states have now decided that pre-service teacher preparation programs and post-employment professional development offerings are lacking a sound and evidence-based focus on the science of reading.

Thus, they are now passing legislation that requires that these two groups of teachers (predominantly at the elementary school level) master reading instruction that is grounded in scientific research. Significantly, some of these laws have specified that teachers need to demonstrate competence in the five components of reading and in other skill areas (e.g., receptive/expressive language, students’ experiential and content knowledge) that contribute to reading proficiency.

Critically, some of this legislation has focused only on teacher knowledge of typical learners. . . rather than on the knowledge and understanding of able, struggling, and disabled readers, and on ensuring that classroom teachers behaviorally demonstrate differentiated instruction and other, related skills, behaviors, and interactions.

Some—but not all—of this legislation has focused on the fact that many university-based (and other) teacher training programs have faculty (as well as clinical and internship supervisors, and other coaches) who do not know (and/or reinforce) the reading science-to-practice. . . but need to.

And some—most, in fact—of the involved legislators have focused on isolated “pieces of the literacy puzzle” without understanding (a) the complexity of the puzzle, (b) which pieces are missing, and (c) which pieces are interdependent with others.

_ _ _ _ _

According to Education Week, in the past three years alone, eleven states have enacted laws to better ensure that evidence-based reading instruction is occurring, at least, in Kindergarten through Grade 3. Significantly, a number of states are expected to follow suit—increasing this number during the coming spring legislative sessions.

[CLICK HERE for this recent Education Week story]

This is interesting because, in May 2015 (not five years ago), the International Literacy Association reported that (a) up to 34 states had no specific professional teaching standards in reading for elementary teachers; (b) up to 24 states had no literacy or reading course requirements; (c) many states had no practicum or internship requirements for literacy practice and supervision; and (d) many states did not require a test to assess competency in reading instruction for teacher-licensure candidates.

[CLICK HERE for our October, 2016 Blog message on:

“Braiding Five Critical Concerns for Children: Reading Instruction, Grade Retention, Skill Remediation, Response-to-Intervention, and Chronic Absences. Why Effective Practice Needs to Dictate Good Policy (Rather than the Other Way Around).”

_ _ _ _ _

- Third: Two recent surveys—of 3,500 principals by the RAND Corp.’s American Educator Panel program, and 1,467 special education teachers in the Council for Exceptional Children’s “State of the Special Education Profession” report—noted that:

* Many principals—especially in schools serving more students of color—felt that they could be doing more to support students with disabilities, but that they felt unprepared to meet these students’ needs as school leaders;

This is significant given that (a) the largest percentage of students with disabilities in most schools are identified as having learning disabilities in reading; and (b) most states in this country have demonstrated extremely poor outcomes relative to improving the reading proficiency of these students.

[CLICK HERE for this February 13, 2020 Education Dive article]

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

What’s Missing in Our Country’s Attempts to Improve Reading?

Education Week crystallized many of the issues discussed above in a special report, “Getting Reading Right,” that was published on December 4, 2019.

[CLICK HERE for the Report]

Some of the important points made in this Report included the following:

- Learning to read is arguably the most important academic experience students will have during their school years. But it’s not a given.

- The “nation’s report card” shows that just 35% of 4th graders are proficient readers despite decades of cognitive research clarifying exactly what skills students need to be taught to read fluently.

- The cognitive science is clear: Teaching systematic phonics is the most reliable way to ensure that children learn how to read words.

- And yet, most K-2 teachers and education professors are using instructional methods that run counter to the cognitive science.

- These flawed methods for teaching reading are often passed down through cherished mentors, popular literacy programs, and respected professional groups.

- Many teachers leave preservice training without clarity on what the cognitive science says about how students learn to read.

- An analysis of the five most-used programs for early reading shows that they often diverge from evidence-based practices.

While a significant contribution to our national discussion, I believe that this discussion has not maximized its effects on all students because of three missing factors:

- We are not conceptualizing literacy instruction and students’ reading proficiency within a systemic, ecological, multi-factored, and multi-tiered continuum that is built on evidence-based blueprints.

- We are developing and implementing policies, procedures, processes, and practices in disorganized, segmented, and disparate ways such that “whole has holes, and the parts never add up to a whole.”

- We are not effectively using the psychoeducational research relative to child development, learning and cognition, psychometrics and assessment, and data-based decision-making and evaluation.

The remainder of this Blog (Part I) will briefly present some of the essential blueprints that must be considered when “piecing together” a sound multi-tiered system of literacy instruction and supports.

Part II of this Blog series will discuss the state of literacy intervention, and the multi-tiered questions needed to address the needs of struggling readers and students with reading disabilities.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Integrating the Blueprints Needed to Maximize Students’ Reading Proficiency

Blueprint 1: Policy (Federal, State, or District)

The first Blueprint is actually a set of principles:

- Policy should not dictate practice. Instead, policy should reinforce effective and comprehensive scientifically-based practice that has been field-tested and proven in multiple, diverse geographic and school settings.

- Policy should be objective, measurable, reasonable, and actionable. It should be flexible enough to allow, without penalty and based on substantiating data, modifications for unique or individual student, staff, or school conditions.

- The functional or practical impact or outcomes of Policy should be evaluated on an ongoing basis both to validate its success (or not), and to identify unintended negative consequences or collateral damage. Policy change or modification should result as needed.

The word “comprehensive” in the first bullet above is defined by the additional Blueprints below.

_ _ _ _ _

But before we move on, let me expand on one example of a poor reading/literacy policy. This is the policy that, in many states, requires schools to retain students in 3rd grade who are not reading at grade level.

We have discussed why this policy is both misguided and has resulted in unintended negative student effects in at least three previous Blogs:

[CLICK HERE for our past Blog on Braiding Five Critical Concerns for Children: Reading Instruction, Grade Retention, Skill Remediation, Response-to-Intervention, and Chronic Absences. Why Effective Practice Needs to Dictate Good Policy (Rather than the Other Way Around).”

[CLICK HERE for past Blog on When Kids Can’t Read: Policy and Practice Mistakes that Make it Worse]

[CLICK HERE for past Blog on Grade Retention is NOT an Intervention: How WE Fail Students when THEY are Failing in School]

_ _ _ _ _

To expand briefly: John Hattie has conducted over 800 meta-analyses involving 50,000 studies and more than 200 million students over the past 15 or more years. Focusing on factors that influence students’ achievement, he has determined that grade retention ranks 136 of the 138 factors that he has investigated.

According to Hattie: “The overall effects from retention are among the lowest of all educational interventions. It can be vividly noted that retention is overwhelmingly disastrous. The effects of retention, based on 861 studies was -0.15—a decline in achievement of .15 standard deviations on achievement tests when a child is retained.”

But, relative to unintended effects: A 2014 Duke study of over 79,000 North Carolina middle school students documented an interdependent “ripple effect” where the middle schools that had more students who had been previously retained had more students who were suspended, had substance abuse problems, and engaged in more fights and classroom disruptions.

The research controlled for both the students’ socio-economic status and their parents’ level of education. Notably, the problems described above occurred not just for the retained students, but also their peers. And while discipline problems increased for all student subgroups, they were more pronounced among white students and girls of all races.

_ _ _ _ _

The bottom line here is that there are many reasons why students are not reading at grade level at the end of Grade 3 (see below). The “big three” reasons relate to (a) student factors; (b) literacy instruction and teaching factors; and (c) literacy curriculum and support/intervention factors.

A diagnostic assessment process should occur with all struggling readers, at the point when they are struggling, to determine the root cause(s) of their problems. Given the research on retention, and the results of this root cause analysis, only those 3rd Grade students who will benefit from a strategically-planned year of retention should be retained.

And then, there is the issue of what you do with a 3rd grade student who is struggling in reading, but not in math or in other academic areas. Do you still retain this student, and potentially make him or her “re-take” academic material that has already been mastered?

THESE are the effects of a policy that does not look at the whole school and the whole child. . . and that does not anticipate or respond to unintended effects or consequences.

This is why such policies need to follow the principles outlined above.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Blueprint 2: Psychoeducational Science-to-Practice

This second Blueprint involves the necessity of contextualizing literacy instruction, and especially how students learn to and become proficient in reading, in psychoeducationally-relevant scientific practices.

This means that the Education Week article on the science of reading, needs to expand into related and relevant areas of scientific practice. These areas include:

- The psychoeducational factors related to student (a) development and maturation; (b) learning and cognition; (c) engagement and motivation; and (d) academic and social, emotional, and behavioral self-management.

- The curriculum and instruction factors related to (a) effective school and schooling processes including the field-testing and validation of effective literacy curricula—prior to their availability in the marketplace; (b) the establishment and maintenance of continuously effective teaching and teaching-of-literacy behaviors; and (c) the decision-making and execution skills needed to differentiate instruction and organize students into effective learning groups.

- The multi-tiered assessment to intervention factors related to (a) the psychometrics of assessment and, especially, of the tests that formatively monitor and summatively evaluate students’ progress in the five areas of literacy; (b) knowing how and when to adapt, supplement, or change instruction; and (c) understanding how to diagnostically assess students who are consistently and/or significantly struggling in reading, and then how to link the results of these assessments to multi-tiered services, supports, strategies, interventions, and comprehensive programs.

_ _ _ _ _

Once again, before we move on, let’s briefly discuss a set of examples of how the science-based psychometrics of assessment and multi-tiered decision-making were not used within the failed “response-to-intervention” approaches advocated during the No Child Left Behind and Reading First years.

[CLICK HERE and find the free monograph, A Multi-Tiered Service & Support Implementation Blueprint for Schools & Districts: Revisiting the Science to Improve the Practice]

Briefly, this monograph outlines seven psychometric and/or decision-making flaws that need to be purged or significantly modified in any school’s current RtI and/or multi-tiered system of supports approaches:

- Flaw #1. Missing the Interdependency between Academics and Behavior

- Flaw #2. Missing the Continuum of Instruction

- Flaw #3. Avoiding Diagnostic or Functional Assessment until it is Too Late

- Flaw #4. Not Linking Assessment to Intervention

- Flaw #5. Focusing on Progress Monitoring rather than on Strategic Instruction or Intervention Approaches

- Flaw #6. Establishing Rigid Rules on Student's Access to More Intensive Services

- Flaw #7. Setting a “Price” on Access to Multidisciplinary Consultation

These flaws were followed up through detailed discussions of ten scientifically-based practices that would result in effective multi-tiered services:

- Practice 1. Multiple gating procedures need to be used during all academic or behavioral universal screening activities so that the screening results are based on (a) reliable and valid data that (b) factor in false-positive and false-negative student outcomes.

- Practice 2. After including false-negative and eliminating false-positive students, identified students receive additional diagnostic or functional assessments to determine their strengths, weaknesses, content and skill gaps, and the underlying reasons for those gaps.

- Practice 3. When focusing—especially at the elementary school level—on helping students to learn and master foundational academic skills (e.g., phonemic awareness, phonetic decoding, numeracy, calculation skills), students should be taught at their functional, instructional levels—regardless of their age or grade level.

- Practice 4. All students should be taught— every year—social, emotional, and behavioral skills as an explicit part of the district’s formal Health, Mental Health, and Wellness standards. These standards should include an articulated and scaffolded preschool through high school scope and sequence document with specific required courses, units, content, and activities. The social, emotional, and behavioral skills should especially be applied to students’ academic engagement, thereby facilitating their ability to work collaboratively in cooperative and project-based learning groups.

- Practice 5. Before conducting diagnostic or functional assessments, comprehensive reviews of identified students’ cumulative and other records/history are conducted, along with (a) student observations; (b) interviews with parents/guardians and previous teachers/intervention specialists; (c) assessments investigating the presence of medical, drug, or other physiologically-based issues; and (d) evaluations of previous interventions.

- Practice 6. Diagnostic or functional assessments evaluate students and their past and present instructional settings. These assessments evaluate the quality of past and present instruction, the integrity of past and present curricula, and interventions that have already been attempted. This helps determine whether a student’s difficulties are due to teacher/instruction, curricular, or student-specific factors (or a combination thereof).

- Practice 7. Diagnostic or functional assessments to determine why a student is not making progress or is exhibiting concerns should occur prior to any student- directed academic or social, emotional, or behavioral interventions. These assessments should occur as soon as academically struggling or behaviorally challenging students are identified (i.e., during Tier I).

- Practice 8. Early intervention and early intervening services should be provided as soon as needed by students. Tier III intensive services should be provided as soon as needed by students. Students should not have to receive or “fail” in Tier II services in order to qualify for Tier III services.

- Practice 9. When (Tier I, II, or III) interventions do not work, the diagnostic or functional assessment process should be reinitiated, and it should be determined whether (a) the student’s problem was identified accurately, or has changed; (b) the assessment results correctly determined the underlying reasons for the problem; (c) the correct instructional or intervention approaches were selected; (d) the correct instructional or intervention approaches were implemented with the integrity and intensity needed; and/or (e) the student needs additional or different services, supports, strategies, or programs.

- Practice 10. The “tiers” in a multi-tiered system of supports reflect the intensity of services, supports, strategies, or programs needed by one or more students.

These practices are integrated into the next blueprint involving the “unit” of instruction, assessment, and intervention.

_ _ _ _ _

Blueprint 3: The Instructional Environment

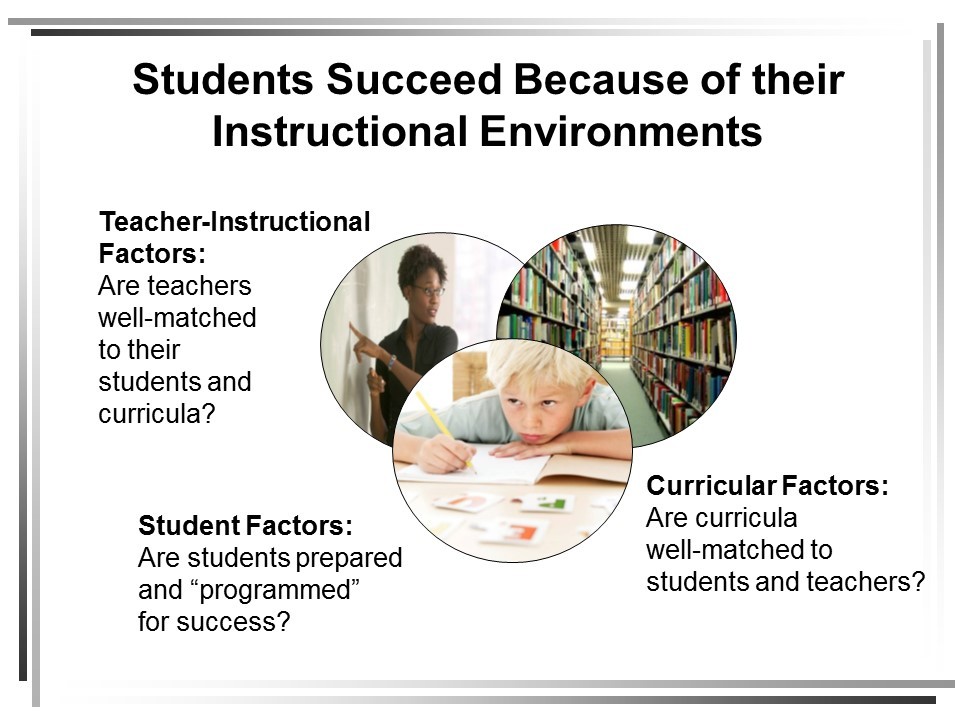

As alluded to in the sections above, students’ proficiency in literacy—in fact, their proficiency in all academic and social, emotional, and behavioral areas is related to their current and past Instructional Environments (see Figure below).

Briefly, the Instructional Environment involves the following interdependent components:

- The teachers who are teaching, and how they organize and execute their classroom instruction (i.e., “Are appropriate instructional and management strategies being used?”);

- The different academic curricula being taught in a classroom, as well as their connection to district scope and sequence objectives, and state standards and benchmarks (i.e., “What needs to be learned?”); and

- The students who are engaged in learning—including their responses to effective instruction and sound curricula, and their ability and motivation to master the material presented (i.e., “Is each student capable, prepared, motivated, and able to learn, and are they learning?”).

Relative to the first two components, students’ literacy learning, mastery, and proficiency is best facilitated when teachers use sound curricula in the following ways:

Preparation

- Teachers are guided by documents that align standards, curriculum, instruction, and assessment.

- Teachers develop unit and/or weekly lesson plans based on aligned units of instruction.

- Teachers physically organize their classrooms (e.g., groups and seating arrangements) in ways that facilitate effective instruction—including project-based or cooperative learning.

- Teachers know the functional reading status, skills, and functioning of all students in their classrooms.

- Teachers ensure that students have the prerequisite skills to be successful in all new learning areas.

- Teachers use objectives‐based pre‐tests or other assessments to determine students’ prior knowledge and skills in all areas of new learning/instruction.

- Teachers use objectives‐based post‐tests or other assessments that validate students’ mastery of new areas of knowledge and/or skill.

- Teachers maintain a record of each student’s mastery of specific learning objectives.

- Teachers test/assess students frequently using a variety of evaluation (formative and summative) methods, and they maintain a record of the results.

- Teachers differentiate assignments (individualize instruction) in response to individual student performance on pre‐tests and/or other methods of assessment or progress monitoring.

Execution

- Teachers begin instruction in a timely way, and sustain it over time so that students spending little time waiting or disengaged.

- Teachers review previous lessons or instruction, providing students with advanced organizers that connect past learning with current or new learning.

- Teachers clearly state the lesson’s topic, theme, objectives, and mastery-level outcomes.

- Teachers stimulate interest in their lessons, topics, and assignments using technology, instructional grouping, and multi-media approaches as indicated.

- Teachers combine instruction with demonstration or modeling, positive practice opportunities, prompts for understanding, formative and summative feedback and evaluation, and transfer of training or application practice opportunities with an explicit goal of facilitating independent learning.

_ _ _ _ _

When students (the third component in the Instructional Environment) are struggling or not responding to effective, differentiated instruction, the next blueprint comes into play. Typically, however, students are successful when they (a) have learned and mastered the prerequisite skills needed by the “next” literacy lesson; (b) are prepared and motivated to learn; (c) are aware, engaged, and interactive; and (d) have the cognitive, metacognitive, and social, emotional, and behavioral self-management skills needed to succeed.

_ _ _ _ _

Blueprints 4 to 6: The Multi-Tiered System of Supports

When students are struggling or not responding to effective, differentiated instruction, teachers—supported by other school personnel—need to use a data-based problem-solving process (Blueprint 4) to identify the root causes of the problem (Blueprint 5). The results of the root cause analysis are then linked to strategic or intensive literacy services, supports, strategies, interventions, or programs (Blueprint 6).

Blueprint 4. The data-based problem-solving blueprint has four steps:

- Problem Identification

- Functional, Diagnostic, or Root Cause Problem Analysis

- Services, Supports, Strategies, Interventions, or Programs

- Progress Monitoring/Formative and Summative Outcomes-Based Evaluation

While the data-based problem-solving process analyzes (as above) the three components of the Instructional Environment (the Teacher-Instructional, Curriculum, and Student components, respectfully), it also ecologically analyzes Classroom and Peer, School and District, and Home and Community factors).

When analyzing factors contributing to a student’s literacy difficulties in the Student component, Blueprint 5 identifies the “Seven High-Hit Student Reasons” for these difficulties.

Blueprint 5. These High-Hit Reasons include the following:

- High Hit #1: Skill Deficits. The student has skill deficits in critical areas of reading. She or he has either not been exposed to effective reading curricula or instruction, or she or he is not learning successfully.

- High Hit #2: Speed of Acquisition. The student is learning, but his/her speed of learning and mastery is slower than other students—either relative to instruction in-the-moment, or instruction over the long-term.

- High Hit #3: Generalization. The student is learning discreet, specific, or isolated skills, but she or he is not blending, integrating, transferring, applying, or generalizing these skills such that—ultimately—she or he is able to decode, read fluently, understand vocabulary, and/or derive meaning and comprehension from text.

- High Hit #4: Conditions of Attribution or Emotionality. The student does not believe that she or he can successfully learn to read, or she or he is experiencing a high enough level of emotionality around some or many parts of the reading (or assessment) process, and this is undermining his or her progress and proficiency.

- High Hit #5: Motivation. The student is not motivated to learn to read. The student has the capacity to learn, or has learned literacy skills in the past, but (now) is not choosing to learn.

- High Hit #6: Inconsistency. The student has or is experiencing (typically) instructional, curricular, or motivational inconsistency that has or is undermining the literacy learning and mastery process.

- High Hit #7: Special Situations. Some special, significant, intense, unique, or individualized situation or circumstance is present that is interfering with the students’ learning.

These situations may require (a) different instructional approaches to reading and/or intensive interventions (e.g., dyslexia); (b) the use of technology-based assistive supports (e.g., students with traumatic brain injured or cerebral palsy); or (c) the recognition that certain reading skills may never be learned but that, through compensatory strategies, literacy (i.e., the comprehension of text) can.

_ _ _ _ _

Blueprint 6: The Positive Academic Supports and Services Continuum.

The last bullet above identified part of the multi-tiered services, supports, strategies, interventions, and programs continuum that we summarize in the acronym PASS.

Grounded by effective, differentiated classroom instruction with well-designed progress monitoring and evaluation, the continuum identifies services, supports, strategies, interventions, and programs—at different, student-needed levels of intensity—to address the root causes when students are struggling or failing to master different facets of literacy.

The PASS continuum consists of the following:

- Assistive Supports

- Remediation

- Accommodation

- Curricular Modification

- Targeted Intervention

- Compensation

Part II of this Blog Series will provide further details on the PASS continuum, while also discussing some of the Problem Identification and Analysis questions needed in the data-based problem-solving process, and outlining a number of specific literacy interventions in the “Targeted Intervention” area above.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

In the Introduction to this Blog (Part I), we discussed the “new and current” rush of policy, publication, media, and legal attention to the quality of literacy instruction—and student outcomes—in our nation’s schools. While triggered by the most-recent National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) results, this persistent problem area has been recently reinforced by:

- A February 20, 2020 legal settlement whereby the state of California agreed to provide $53 million for early literacy instruction to resolve a 2017 lawsuit asserting that petitioning students’ constitutional rights were violated when schools failed to teach them to read.

- An influx of state legislatures that are passing laws requiring pre-service and classroom teachers to be taught—and to demonstrate their proficiency in—the science of reading.

- Two recent national surveys that revealed how many school principals—especially in schools serving more students of color—felt that they were not fully supporting students with disabilities, and that they felt unprepared to meet these students’ needs.

Our Introduction cited a recent (December 4, 2019) series of articles in Education Week, “Getting Reading Right,” that document these and other problems in literacy training and instruction. But it also emphasized that this national discussion and all of the legislative, training, policy, and practice efforts to date are missing three critical factors:

- We are not conceptualizing literacy instruction and students’ reading proficiency within a systemic, ecological, multi-factored, and multi-tiered continuum that is built on evidence-based blueprints.

- We are developing and implementing policies, procedures, processes, and practices in disorganized, segmented, and disparate ways such that “whole has holes, and the parts never add up to a whole.”

- We are not effectively using the psychoeducational research relative to child development, learning and cognition, psychometrics and assessment, and data-based decision-making and evaluation.

The rest of this Blog (Part I) presented the essential blueprints that must be considered when “piecing together” a sound multi-tiered system of literacy instruction and supports.

These blueprints included the following:

Blueprint 1: The Principles Underlying Effective Educational Policy

_ _ _ _ _

Blueprint 2: A Psychoeducational Science-to-Practice Blueprint for Effective Literacy Instruction and Multi-Tiered Services and Supports

The seven flaws and ten scientifically-based practices that create an effective, comprehensive multi-tiered system of supports for literacy.

_ _ _ _ _

Blueprint 3: Understanding the Instructional Environment and Its Contribution to Student Reading Proficiency

- Teacher/Instructional Factors

- Curriculum and Support Factors

- Student Learning and Mastery Factors

_ _ _ _ _

Blueprint 4. The Data-based Problem-Solving Blueprint for Struggling and Failing Readers

_ _ _ _ _

Blueprint 5. The Seven High-Hit Reasons Why Students Struggling or Fail in Reading

_ _ _ _ _

Blueprint 6: The Multi-tiered Positive Academic Supports and Services Continuum

_ _ _ _ _

Part II of this Blog series will continue to discuss the state of literacy intervention (linking Blueprint 5 and Blueprint 6), and the multi-tiered questions needed to address the needs of struggling readers and students with reading disabilities.

_ _ _ _ _

I hope that this Blog has provided a comprehensive perspective of the complexity of literacy instruction in our schools, and the challenges that we face in helping more students to become proficient readers.

I appreciate the time that you invest in reading these Blogs, and your dedication to your students, your colleagues, and the educational process.

Please feel free to send me your thoughts and questions.

And please know that I continue to work on-site with schools across the country. . . helping them to maximize their instructional and support resources as they fully implement these blueprints with high levels of success and impressive student outcomes.

I would love to work with your school or district. Contact me at any time.

Best,