Call Congress: The Tainting of RtI, PBIS, MTSS, and SEL

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

In Poker, a player “doubles down” when they have a losing hand, but they want the other players to think that it’s a winner. And so, they double what was originally a losing bet (when they should be folding instead) to make it appear that they are eminently confident that they have a winner. If the bluff works, the other players fold, and the winner collects the pot (usually without revealing the bluff).

Recently, “doubling down” has become popular in politics. Indeed, some news channels have described our President as “doubling down” when he originally makes an illogical, untenable, or fabricated statement, then is confronted by the facts, and then reasserted his statement more vociferously.

And finally, sometimes doubling-down occurs in life. For example, when people face a losing situation or take an unwise risk, they may decide to put more energy, resources, or time into it in an effort to turn “lemons into lemonade.”

This is what some business start-ups do when they buy massive amounts of prime-time advertising for a new product that just is not catching on. Here, the product either “gets hot,” or the company goes out of business.

_ _ _ _ _

When a private company decides to double down, it is the essence of capitalism in a free market economy. But when this scenario involves the federal government and your tax dollars, there should be a pause for reflection.

And if a federal government agency doubles down on its own agenda, program, or initiative—and the decision involves (or has the appearance of involving) a political conflict of interest or fiduciary malfeasance, there should be moral, ethical, and/or legal outrage.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

The U.S. Department of Education’s Near-Exclusive “Advocacy” of RtI, PBIS, and MTSS

In past Blogs, I have presented the data and documentation to demonstrate that the U.S. Department of Education (USDoE)—at the very least—has given its RtI, PBIS, and MTSS frameworks preferential treatment, funding, and funding opportunities.

It has done this, often through its funded National Technical Assistance (TA) Centers, in ways where:

- It has misrepresented the federal law;

- It has recommended or used only these programs in other federal grant programs—serving to extend these frameworks’ “legitimacy” and national reach;

- By default, it has ignored, minimized, or failed to similarly acknowledge other evidence-based or effective models or programs that (often) report better results than their frameworks; and

- It has done all of this as part of a conscious agenda whose goal is to “brand” their frameworks in national prominence.

While, as above, representing multiple conflicts of interest (or, at least, the appearance of some), these actions began in 1997 with the first federal grant award to the National PBIS TA Center and have continued since (see below).

Collectively. . .

The lack of success of these frameworks (see citations below) has cost districts and schools millions of hours of organizational and staff development time and resources, and our country and districts millions of dollars of taxpayer funds. . . with no real or sustained return on investment.

More important are the services, support, programs, and interventions that academically struggling and behaviorally challenged students have not received because of the misguided advocacy of these frameworks.

_ _ _ _ _

In this Blog, I am going to give examples (with citations to earlier Blogs) of the assertions above.

But then, I am going to reveal how the U.S. Department of Education (USDoE) doubles down on these frameworks—especially when major research studies show them to be ineffective. The USDoE does this by funding new studies with your tax dollars. . . in an attempt to “prove” that earlier research was incorrect, and that their frameworks are actually beneficial.

_ _ _ _ _

Is the USDoE Misrepresenting Federal Law? MTSS, PBIS, and RtI

The current Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA/ESSA, 2015) includes the terms “multi-tiered system of supports” (five times) and “positive behavioral interventions and supports” (three times). The first term does not appear in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004), and the second term appears in IDEA six times—although there are innumerable variations of this phrase sprinkled across IDEA.

The term “response-to-intervention” (i.e., RtI), or any of its derivatives, does not appear in ESEA/ESSA. Similarly, by way of history, the explicit term “response-to-intervention” never appeared in IDEA, nor did not appear in the previous version of ESEA (the No Child Left Behind Act).

Indeed, the closest that IDEA came to using the term “response-to-intervention” was in the section on learning disabilities where it stated,

“In determining whether a child has a specific learning disability, a local educational agency may use a process that determines if the child responds to scientific, research-based intervention as a part of the evaluation procedures described in paragraphs (2) and (3).”

The critical issue here is this:

ESEA and IDEA both reference “multi-tiered system of supports” and “positive behavioral interventions and supports” as generic terms, in lower case words, and without acronyms. This means that federal law does not require either the MTSS or the PBIS frameworks advocated by the U.S. Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) or its tax-funded and related national TA centers.

And yet for years, OSEP and the USDoE have confused the public by making it appear that their upper-case frameworks are required by federal law.

For example, on the PBIS and the Law page on the National PBIS TA Center’s website (https://www.pbis.org/policy-and-pbis/pbis-and-the-law), the excerpted entry below has been present—virtually intact—for over a decade. I have bolded [with my comments] the areas that represent mis-statements or misrepresentations.

Positive Behavioral Supports and the Law

Since Congress amended the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in 1997, Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports has held a unique place in special education law. PBIS, referred to as Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports in IDEA, is the only approach to addressing behavior that is specifically mentioned in the law. This emphasis on using functional assessment and positive approaches to encourage good behavior remains in the current version of the law as amended in 2004.

[NOTE: The National PBIS TA Center does not state that the PBIS acronym never appears in either law, and that the terms are generic and in lower case. At the very least, they introduce the confusion between the upper and lower case terms and misrepresent the law. Their statement that PBIS is the only approach referenced in the law is inaccurate. IDEA 2004 also includes the following terms: to “positive behavioral support,” “behavioral supports,” “positive behavioral interventions,” “behavioral supports and research-based systemic interventions.”]

_ _ _ _ _

Why Emphasize PBIS?

[A historic background section has been deleted.]

Congress recognized the need for schools to use evidence-based approaches to proactively address the behavioral needs of students with disabilities. Thus, in amending the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act both in 1997 and in 2004, Congress explicitly recognized the potential of PBIS (my emphasis) to prevent exclusion and improve educational results in 20 U.S.C. § 1401(c)(5)(F):

(5) Almost 30 years of research and experience has demonstrated that the education of children with disabilities can be made more effective by—

(F) providing incentives for whole-school approaches, scientifically based early reading programs, positive behavioral interventions and supports, and early intervening services to reduce the need to label children as disabled in order to address the learning and behavioral needs of such children (emphasis above by the National PBIS TA Center).

[NOTE: Here you see, very clearly, the misrepresentation of the law by the PBIS National TA Center in confusing their upper-case framework with the law’s generic lower-case term and referenced approaches.]

_ _ _ _ _

IDEA's Requirements to Use Functional Assessments and Consider PBIS

While Congress recognized the potential of PBIS, it was hesitant to dictate any one educational approach to schools. Indeed, Congress was careful to balance the need to promote the education of children with disabilities and the right of states to govern their own educational systems. IDEA's requirements regarding the use of functional assessments and PBIS reflect this balance. IDEA requires:

- The IEP team to consider the use of Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports for any student whose behavior impedes his or her learning or the learning of others (20 U.S.C. §1414(d)(3)(B)(i)).

- A functional behavioral assessment when a child who does not have a behavior intervention plan is removed from their current placement for more than 10 school days (e.g. suspension) for behavior that turns out to be a manifestation of the child's disability (20 U.S.C. §1415(k)(1)(F)(i)).

- A functional behavioral assessment, when appropriate, to address any behavior that results in a long-term removal (20 U.S.C. §1415(k)(1)(D)).

To examine whether federal law (IDEA) requires the IEP team to consider PBIS in response to a particular situation, or to identify other legal requirements for a situation involving the behavior or discipline of a student with a disability, we recommend you try out this online IDEA discipline provisions tool.

[NOTE: While it the begins this section by accurately stating that Congress was “hesitant to dictate one educational approach to schools,” the National PBIS TA Center reverts to form by confusing their upper-case framework with the law’s generic lower-case term and referenced approaches—see the bolded phrases above.]

_ _ _ _ _

IDEA, Professional Development and PBIS

Congress further recognized that, to encourage implementation of PBIS, funds needed to be allocated to training in the use of PBIS. Thus, IDEA provides additional support for the use of PBIS in its provisions by authorizing states to use professional development funds to "provide training in methods of . . . positive behavioral interventions and supports to improve student behavior in the classroom" (20 U.S.C. §1454(a)(3)(B)(iii)(I)). Congress also provided for competitive grant funds that can be used to:

- Ensure that pre-service and in-service training, to general as well as special educators, include positive behavior interventions and supports (20 U.S.C. §1464 (a)(6)(D) & (f)(2)(A)(iv)(I)).

- Develop and disseminate PBIS models for addressing conduct that impedes learning (20 U.S.C. §1464(b)(2)(H)).

- Provide training and joint training to the entire spectrum of school personnel in the use of whole school positive behavioral interventions and supports (20 U.S.C. §1483(1)(C & D)).

Professional development is key to proper implementation of PBIS and the improved behavioral outcomes that PBIS can foster. After all, for an IEP team to truly "consider" the use of PBIS requires knowledge of PBIS, discussion of its use, and the capacity to implement PBIS to improve outcomes and address behavior.

[NOTE: More of the same—enough said.]

_ _ _ _ _

Moving On: Beyond these publicly-posted misrepresentations of federal law, I have attended close to one hundred PBIS national and state presentations over the years, where PBIS national leaders have even more directly stated that “Federal law requires the PBIS framework.”

_ _ _ _ _

For the past fifteen years or more, OSEP staff have allowed this misinterpretation. I know this because I formally protested the website entry above over fifteen years ago (a) to the Assistant Secretary directing OSEP… and (b) in a hand-delivered letter that I personally gave to Secretary Arne Duncan after a presentation in Little Rock, Arkansas.

This upper-case/lower-case differentiation is not semantics, and this is not an “innocent” oversight.

From my perspective, this is a pure powerplay that is predicated on OSEP’s belief (and experience) that most educators (a) trust the U.S. Department of Education, assume that it acts in the best interests of all students, and believe that its recommended practices are based on the most up-to-date research available; and (b) think that the U.S. Department of Education and OSERS/OSEP have no reason to promote (and fund) their own agenda.

Relative to MTSS, the USDoE and OSEP have similarly confused the “multi-tiered systems of support” language in ESEA with its own MTSS framework that they have funded and developed through relevant national TA centers. Once again, many unaware and trusting school practitioners have accepted the incorrect assumption that ESEA requires the MTSS framework created by and largely advocated through OSEP.

Relative to other facets of RtI and MTSS, the USDoE and OSEP have been more “subtle.” Here, they have largely worked through each state’s department of education (which they evaluate on an annual basis prior to releasing each year’s federal dollars to them). The “work” has largely focused on promoting the RtI and now MTSS frameworks by providing “free” consultation from the relevant National TA Centers and regional resource centers, and by “encouraging” the use of federal funds for these frameworks.

In addition, many state department of education colleagues across the country have privately shared with me their fears that a rejection of the USDoE’s frameworks might result in fewer federal funds, or more intensive USDoE “attention” during their annual and triennial state education performance reviews.

_ _ _ _ _

Is the USDoE Inappropriately Recommending the Use of Other Federal Funds for PBIS?

The USDoE has long encouraged Chief State School Officers and other state governmental officials to use different types federal funds and federally-funded programs to support or implement OSEP’s (and other departments’) “home-grown” frameworks.

The most egregious example here is the PBIS framework, where PBIS was explicitly recommended to the nation’s Chief State School Officers in direct letters sent by U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan (a) for the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) funding in February, 2009, and (b) to address the national epidemic of seclusions and restraints—especially for students with disabilities (July 31, 2009).

[See details in the “A Brief U.S. Department of Education/PBIS History” section of my March 2, 2019 Blog:

Congress Take Note: How to Really Address the School Seclusion and Restraint Epidemic. The U.S. Department of Education Keeps Pushing PBIS, but PBIS Ain’t Got Nothing to Give (Part I)

In addition to the above, the PBIS framework was exclusively advocated (a) in the U.S. Department of Education’s 2011-2014 and 2014-2018 Strategic Plans; (b) in the White House’s Safe Schools brief released in response to the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre; and (c) as a required partner in the five-year federal School Climate Transformation grants awarded to 71 school districts in 2014, and 25 state departments of education collectively in 2014 and 2018.

Relative to the latter School Climate Transformation Grants, the Request for Proposals not only expressed a preference for grantees to use the PBIS framework, but it required grantees to budget for and attend a national PBIS conference each October—for the five years of the grant. Thus, all of the grantees—whether they are using the PBIS framework or not—are required to support the National PBIS TA Center’s annual conference.

Once again, the USDoE’s singular advocacy for the use and funding of the PBIS framework that it initiated and has helped to develop since 1997, at least has the appearance of a conflict of interest. More functionally, however, the exclusive PBIS attention and promotion has concurrently minimized national attention to other evidence-based or effective multi-tiered schoolwide discipline models or programs, thereby disadvantaging their use and growth.

This has been a conscious agenda on the part of the USDoE and OSEP. Indeed, the OSEP staff overseeing the national PBIS initiative have admitted to their goal of “branding PBIS.”

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Who Testifies for the USDoE in Congress?

When there is a national crisis, important pending legislation, or funding questions before it, Congress typically holds hearings and invites the USDoE to recommend speakers. Not surprisingly, the USDoE most often invites directors from the relevant national TA centers that it funds.

The problem here is that, given the limited timeframe for most hearings, the committee or subcommittee receives a potentially limited and biased view of the issues at-hand. At the very least, they hear what the USDoE wants them to hear, and they may not understand that there are others who disagree with the USDoE’s views and who have significantly different and defensible perspectives.

This occurred just recently at a Congressional hearing on seclusions and restraints in our nation’s schools.

Specifically, on February 27, 2019, an education subcommittee of the House of Representatives conducted a hearing where the most-recent number of seclusions and restraints across the country was reported, possible alternative approaches were outlined, and the role of the federal government in decreasing seclusions and restraints was discussed.

During this hearing, the U.S. Department of Education promoted George Sugai’s testimony. Sugai has been the Co-Director of the National Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) Technical Assistance (TA) Center since its inception in 1997. Rather than talking about the root causes of the seclusion and restraint dilemma in our schools, Sugai instead spent some of his precious testimony time promoting his (and OSEP’s) PBIS framework.

_ _ _ _ _

Summary

As noted above, the USDoE and OSEP have used their “bully pulpit” to dominate the agenda, practices, and discussions in education for decades. To a large degree, they have successfully controlled what educators hear, the books that are published and that they read, and the professional development activities that they are required or choose to attend.

By default, the USDoE and OSEP’s promotion of the RtI, PBIS, and MTSS frameworks has resulted in other evidence-based models or programs being ignored, minimized, or unable to compete. This is especially problematic given the studies over the years that have questioned the efficacy especially of the RtI and PBIS frameworks.

And so, the story continues.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

National Studies Question the Validity of the RtI/MTSS and PBIS Frameworks

As they prepare to meet the expectations of ESEA/ESSA, state departments of education and school districts nationwide must recognize that a number of major research and evaluation reports—some commissioned or conducted by the federal government—have shown that the federal RtI/MTSS and PBIS frameworks has not produced expected student outcomes.

Thus, as state departments of education and districts rethink their multi-tiered systems of supports, they need to recognize and correct the flaws that have undermined these earlier (and, sometimes, current) RtI and MTSS approaches.

[CLICK HERE to access the Project ACHIEVE website where you can receive our free analysis, A Multi-Tiered Service & Support Implementation Blueprint for Schools & Districts: Revisiting the Science to Improve the Practice]

_ _ _ _ _

(Negative) Results of the Largest Federal RtI Study of its Kind

In the area of RtI, Balu, Zhu, Doolittle, Schiller, Jenkins, and Gersten (2015) analyzed the literacy progress of approximately 24,000 first through third grade students in 13 states. Commissioned by the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences and the largest federal investigation of its kind, the authors statistically compared 146 schools that had been implementing key elements from the U.S. Department of Education’s Response-to-Intervention (RtI) framework in literacy for at least three years with 100 randomly-selected comparison schools in the same 13 states, who were not implementing RtI.

Student outcomes were evaluated primarily using individually-administered norm-referenced tests, as well high-stakes state proficiency tests. The students’ lack of progress in literacy, in the 146 RtI schools, qualified them for Tier II RtI interventions. The students in the 100 Comparison schools barely made or just missed their schools’ cut-offs for Tier II intervention. Most of the schools were using either DIBELS or AIMSweb as their literacy screening instruments.

The reported results were as follows:

- The 1st graders receiving Tier II interventions performed 11 percent lower on the reading assessments than the comparison students who barely missed qualifying for the Tier II intervention approaches.

- The 2nd and 3rd graders receiving Tier II interventions experienced no significant reading benefits---although they did not lose ground.

- At Grade 1, only four of the 119 schools studied found data-based benefits for their Tier II students, while 15 schools had negative effects for their Tier II students.

[100 schools showed no benefits despite all of the staff and student time and resources expended.]

- At Grade 1, 86% of students who began in Tier I remained in Tier I; 50% of the students who began in Tier II remained there; and 65% of the students in Tier III remained.

- Across the Grade 1 student sample, 13% of the students moved to a more intensive Tier, and 14% moved to a less intensive Tier. [The percentages of students moving were smaller in Grades 2 and 3.]

- Students already receiving special education services or who were “old for grade” (probably due to delayed entrances or retentions) had particularly poor results when they received Tier II interventions.

- For all students, the reading results did not significantly differ for students from different income levels, racial groups, or native languages.

In addition to the primary results above, a “close reading” of the evaluation report revealed some important additional findings for the RtI schools:

- 79% of the schools for the Grade 1 students, 75% of the schools for Grade 2, and 80% of the schools for Grade 3 used only ONE screening test when placing their students in Tier II interventions in the Fall.

- Between 31% (Grade 3) and 38% (Grade 1) of the students in the study were placed into Tier II or III interventions based only on the screening test.

- The “interventions” tracked simply involved small-group instruction or one-on-one tutoring.

- For the Below Grade Level students in the intervention groups, 37% of the Grade 1 students, 28% of the Grade 2 students, and 22% of the Grade 3 students received their interventions from paraprofessionals—not certified teachers or reading or other specialists.

It is hard to dismiss the most important results from this study.

These especially include that (a) the first grade students receiving Tier II RtI interventions ended up worse off than the Comparison students who stayed in their general education classrooms without supplemental intervention; and (b) the second and third grade students receiving Tier II RtI interventions (which involved at least 120 additional minutes of interventions per week during each school year) were no better off than the Comparison students who stayed in their general education classrooms—despite these extensive (and expensive) supplemental intervention services.

_ _ _ _ _

A USDoE Study Evaluating and Questioning the Efficacy of PBIS

As noted above, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education Programs has singularly promoted its multi-tiered Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) framework for over 20 years through its federally-funded national Technical Assistance Center.

And yet, a major national study—that was largely hidden to the public by the USDoE (more about that in the last section)—seriously questions the efficacy of the PBIS framework.

A Qualitative Analysis of PBIS

This qualitative study was actually commissioned by the USDoE’s Institute of Education Science (IES) on a contract to a joint research team from the University of South Carolina’s School Mental Health Team, Tanglewood Research Inc., and Research Triangle Institute (RTI) International.

The goal of the study was to evaluate—circa 2012-2013—the status of the science, practice, and outcomes of school-wide positive behavioral support systems (SWPBS) across the United States, and to design a comprehensive study to evaluate the efficacy of these systems that would subsequently be funded. The study investigated four specific approaches: PBIS, Safe and Civil Schools, BEST, and my Positive Behavioral Support System (PBSS) approach through Project ACHIEVE.

The study was “reported” in four appendices (not as a publication in its own right) as part of a “Presolicitation Announcement” for the subsequent study on the Federal Business Opportunities (not the Federal Register as with most educational grants like this one).

[CLICK HERE for the Announcement and Appendices]

As noted, it is significant that the study was not published—in its own right, and as is typical for these types of government contracts—as part of its own publicly-disseminated report.

It is my belief that this was done for one or more reasons. My best guess is that the primary reason was to keep the disappointing (at best) PBIS outcomes reported in the study from the public. Indeed, at this point in time after over 15 years of National PBIS TA Center funding by the USDoE and taxpayers across the country, there was not much to show for the investment.

But the second guess—especially as the “study” was being reported in a new, upcoming Request for Proposals (see the last section in this Blog)—was that the study was designed to provide a rationale for an already-made USDoE decision that they needed to invest more money to validate PBIS.

To support this hypotheses, the four appendices in the Federal Business Opportunities Pre-solicitation, consisting of reports published by the contracted teams from the University of South Carolina’s School Mental Health Team, Tanglewood Research Inc., and Research Triangle Institute (RTI) International, were titled:

- Appendix A1: Review of Approaches to Training Schools in SWPBS

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

- Appendix A2: SWPBS Design Options Report

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

- Appendix A3: SWPBS Summary of Expert Panel Meeting and Follow-Up Discussion

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

- Appendix A4: Training Provider Review

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

The PBIS Results of Study 1. Based on interviews with the National PBIS TA Center Directors and other critical PBIS trainers, the following questionable PBIS practices and conclusions were stated and/or evident from the Appendices above [with my comments]:

- PBIS is a framework and not a sequential model. Thus, schools can choose whatever PBIS activities to implement that they want—in whatever sequence, place, or student group that they want.

[This means that cross-school comparisons of PBIS’s efficacy is virtually impossible, and one cannot generalize the (positive or negative) results from one PBIS school (or study) to another.]

- Regardless of the thousands of schools “implementing” PBIS, the National Directors believed that approximately half of the schools might be implementing with “a reasonable level of integrity.” The Report stated, ”George Sugai (one of the National PBIS TA Co-Directors) cannot say whether SWPBS is being implemented with fidelity” in the approximately 18,000 schools (that) have been trained with first generation trainers.”

[The issue here is that the number of schools implementing PBIS is not what is important, it is the objective, demonstrable, and sustainable student-centered PBIS results that are important.]

- PBIS has traditionally used decreases in Office Discipline Referrals (ODRs) and school suspensions or expulsions as the primary outcome “validating” its framework. ODRs have been methodologically demonstrated to be horribly unreliable.

[Indeed, all it takes is a building principal to say, “Don’t send unruly students to the Office,”. . . or a classroom teacher to not send these students for fear of being negatively evaluated. . . or an assistant principal to decide “which offenses” really count as “true” disciplinary offenses (rather than as opportunities to “counsel” with a student). . . to introduce bias into and/or to contaminate a school’s data.

But beyond this, a more accurate outcome for a school-wide positive behavioral system is the development and demonstration of students’ social, emotional, and behavioral self-management skills and academic engagement. Indeed, even if a school-wide behavioral system was able to decrease the inappropriate student behaviors that cross the disciplinary threshold of needing to be sent to the Principal’s Office. . . this does not mean that the students are “behaving” in class, are prosocially interacting with others, and/or are fully academically engaged. It just means that extreme levels of misbehavior have been diminished.

This was recognized in the commissioned Report as one expert was quoted to say that “office discipline referral (ODR) data is helpful but should not be the only source of student behavior measurement. Teacher ratings provide another source for student behavior data. Also, teacher ratings of behavior are most reliable for younger students as opposed to student self-report surveys.” She (the expert) suggested considering peer ratings for measuring students’ social competency skills.]

- Back to the Report: Most PBIS schools focus predominantly on behavior in the Common Areas of the school (i.e., the hallways, bathrooms, cafeteria, etc.) and not in the classroom where students spend 85% of their time.

In addition:

- The PBIS Triangle has never been validated. The Tier I (80%—All), Tier II (15%—Some), and Tier III (5%—Few) convention was made up by the National PBIS Directors for community-based epidemiological research that does not apply to education.

[CLICK HERE for a February 16, 2019 Blog on this topic]

- PBIS recommends that challenging students sequentially receive Tier I to Tier II to Tier III services, and that record reviews and functional assessments of individual student behavior be delayed until Tier III.

[There is no research to support this practice, and it has resulted in (a) individual student interventions and supports being delayed to some students; (b) an increase in student resistance to intervention (because initial interventions were inappropriate and unsuccessful as they were implemented without reviewing students’ background information and histories); and (c) the need for more intensive interventions—even within Tier III—because student problems have gotten worse or more complicated because of the delays and the previous inappropriate interventions.]

- For years, virtually the only Tier II interventions in the PBIS framework were Check and Connect, and Check-In and Check-Out—even though these interventions do not address the root causes of most students’ inappropriate behavior.

[In addition, the PBIS framework rejected social skills instruction for almost the first 15 years of its existence. Eventually, it agreed that social skills training was needed. . . but only at the Tier II level. Here, the National PBIS leaders failed to recognize that social skills are needed by all students in Tier I, and that the absence of this training was resulting in the need to “remediate” large numbers of students—who simply had never learned these skills—in a more intensive (Tier II) and (typically) pull-out setting.]

- PBIS is recommending universal social, emotional, and behavioral screening of all students in a school without describing the scientifically-appropriate multiple-gated procedures needed to do this accurately and effectively.

Finally:

- Beyond the implementation integrity that even the National PBIS Directors questioned, most PBIS schools were found to only implement PBIS framework activities at the Tier I level, and many schools were not sustaining their PBIS practices for more than three years.

[The PBIS framework largely recommends that schools sequentially implement Tier I, then Tier II, then Tier III. This misses the fact that most schools have behaviorally challenging students who need immediate service and support (e.g., (Tier III) interventions. These students cannot wait for two to three years for their school’s PBIS Tier I and Tier II activities to be secured.

But more practically: If the intervention needs of students with challenging (Tier III) behaviors are not immediately and successfully addressed at the beginning of the PBIS implementation process, many staff will be unable or unwilling to implement even the Tier I activities.]

- The PBIS framework is largely implemented by a PBIS team that comes from each implementing school. This team receives large-group training (with other teams) in off-site settings that are off of school grounds.

[Said differently, virtually no PBIS training occurs—by trained national or state PBIS leaders—with entire school faculties at their own schools. Moreover, there is little or no on-site and direct PBIS consultation or technical assistance provided to implementing schools by experienced and expert PBIS Trainers or Facilitators. Thus, each school’s PBIS team (and/or local and inexperienced Facilitator) is left to do its own planning, implementation, and evaluation at its own school site.]

- In some states, a state-level PBIS team annually evaluates the PBIS implementation of its schools. This evaluation and its “Gold,” “Silver,” and “Bronze” awards are largely based on the implementation of activities, and not students’ social, emotional, or behavioral outcomes.

[In fact, one part of the evaluation is that students and staff must be able to recite the global PBIS behavioral expectations in the school. This results in schools spending (wasting) valuable instructional time—immediately prior to the Evaluation Team’s visit—grilling the students and staff in case they are asked for “a recitation.” This “game-playing” element serves to undermine the true importance of school-wide discipline and student self-management for many students and staff.

Once again, the substantive outcomes of a school-wide positive behavioral support system should be: (a) changes in school climate and school safety; (b) improvements in staff interactions and classroom behavior management; and (c) increases in students’ interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control and coping skills and behaviors. This is not the focus in most PBIS schools relative to their state-level (annual) evaluations.]

_ _ _ _ _

PBIS and Disproportionate Discipline Referrals

Perhaps no behavioral outcome is more connected to PBIS’s core outcomes than the disproportionate number of office discipline referrals experienced by students of color and students with disabilities. And yet, here, very little progress has been made nationally in this area.

Indeed, on April 4, 2018, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) published a study, K-12 Education: Discipline Disparities for Black Students, Boys, and Students with Disabilities, that analyzed the discipline data for the 2013-2014 school year from nearly every public school in the country.

The Report’s Executive Study identified the rationale for the study as follows:

GAO was asked to review the use of discipline in schools. To provide insight into these issues, this report examines (1) patterns in disciplinary actions among public schools, (2) challenges selected school districts reported with student behavior and how they are approaching school discipline, and (3) actions Education and Justice have taken to identify and address disparities or discrimination in school discipline.

GAO analyzed discipline data from nearly all public schools for school year 2013-14 from Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection; interviewed federal and state officials, as well as officials from a total of 5 districts and 19 schools in California, Georgia, Massachusetts, North Dakota, and Texas. We selected these districts based on disparities in suspensions for Black students, boys, or students with disabilities, and diversity in size and location.

The Executive Study then summarized the results:

Black students, boys, and students with disabilities were disproportionately disciplined (e.g., suspensions and expulsions) in K-12 public schools, according to GAO’s analysis of Department of Education national civil rights data for school year 2013-14, the most recent available. These disparities were widespread and persisted regardless of the type of disciplinary action, level of school poverty, or type of public school attended. For example, Black students accounted for 15.5% of all public school students, but represented about 39% of students suspended from school—an overrepresentation of about 23 percentage points.

Officials GAO interviewed in all five school districts in the five states GAO visited reported various challenges with addressing student behavior, and said they were considering new approaches to school discipline. They described a range of issues, some complex—such as the effects of poverty and mental health issues. For example, officials in four school districts described a growing trend of behavioral challenges related to mental health and trauma. While there is no one-size-fits-all solution for the issues that influence student behavior, officials from all five school districts GAO visited were implementing alternatives to disciplinary actions that remove children from the classroom, such as initiatives that promote positive behavioral expectations for students.

Critically, this study demonstrates that, during the past ten-plus years of trying to systemically decrease disproportionality in schools, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified the root causes of the students’ challenging behaviors, and we have not linked these root causes to strategically-applied multi-tiered science-to-practice strategies and interventions.

Moreover, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified and addressed the root causes of staff members’ inappropriate and/or unuseful interactions and reactions to the behavior of African-American students and students with disabilities. . . reactions that sometimes involve bias, prejudice, and/or intolerance; and that, at times, are the core reasons for some disproportionate Office Discipline Referrals.

And finally, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified and addressed the root causes of administrators’ disproportionate decisions with these students as they relate to suspensions, expulsions, law enforcement involvement, and referrals to alternative school programs.

So how does PBIS fit here?

As noted above, millions of federal tax dollars have been invested in this area, over the past decade or more, through the U.S. Department of Education’s Technical Assistance Centers. The National PBIS TA Center has been run by the same national directors out of the University of Oregon (and, recently, additional partner universities) since 1997.

While clearly there are intervening factors at the local and state levels, I believe that the National PBIS Directors need to be held accountable for the disproportionality results cited in the April, 2018 GAO Report above. At the very least, they should be responsible for providing a formal explanation to the public as to where (in real schools) and why their framework has been successful, and where and why it has not worked—in what looks like many, many more schools.

_ _ _ _ _

PBIS and Seclusions and Restraints

In mid-January (2019), the U.S. Department of Education’s Offices for Civil Rights (OCR) and Special Education and Rehabilitative Services (OSERS) announced an initiative to “address the inappropriate use of restraint and seclusion” on students with disabilities. OCR and OSERS will attend to three specific areas: (a) Increasing the number of compliance reviews in districts across the country; (b) Disseminating more legal and intervention resources focused on prevention and alternative responses; and (c) Improving the integrity of incident reporting and data collection.

On February 27, 2019, an education subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives conducted a hearing where the number of seclusions and restraints across the country was updated, possible alternative approaches were outlined, and the role of the federal government in decreasing seclusions and restraints was discussed. At this hearing, George Sugai, the Co-Director of the National PBIS TA Center, testified.

Sugai (and others’) testimony was described as follows in a February 27, 2019 Education Week article:

“Nationally the use of restraint and seclusion is very rare," Nowicki (the director of education, workforce, and income security at the U.S. Government Accountability Office) said (in her testimony to the subcommittee).

But when it does happen, said George Sugai, a University of Connecticut professor, the consequences can be significant: "They do not develop or maintain positive relationships with others. They do not enhance their capacity to function in more normalized environments." Sugai also stressed that students should not be restrained or secluded to punish them or to stress the importance of following classroom rules.

While the Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports is not a magic bullet, he said that using the framework can help educators deal with situations that can lead to restraints and seclusions.

It is critical to note that Sugai did not say that the PBIS framework, based on multiple controlled and objectively implemented studies, has demonstrated its capacity to prevent or decrease (over time) school seclusions or restraints with the most behaviorally challenging students who (a) are present in many schools, and (b) are the students who are most often secluded or restrained.

He said, instead, that PBIS “can help.” Once again, he did NOT say that PBIS will or has documented its definitive ability “to help.”

And what does the current national seclusion and restraint data look like?

_ _ _ _ _

The National 2015-2016 School Year Incident Data. The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) oversees the Civil Rights Data Collection system (CRDC) that surveys all public schools and school districts in the United States to collect data and analyze issues that impact education equity and opportunity for students across the country. On April 24, 2018, OCR released its report on the 2015-2016 school year data that included the seclusion and restraint data involving more than 50.6 million students at over 96,000 public schools across the country.

[CLICK HERE to see a full analysis of these data in my March 16, 2019 blog, “States Take Note: How to Really Address the School Seclusion and Restraint Epidemic. What State Departments of Education Need to Learn If Using PBIS to ‘Solve’ this Problem (Part II)”]

During the 2015-2016 school year:

- Over 84,000 students covered under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act were restrained or secluded (69% of the more than 122,000 students restrained or secluded nationally).

- 23,760 students with disabilities were secluded (66% of the 36,000+ seclusions for all students across the country).

- 61,060 students with disabilities were restrained (71% of the 86,000+ restraints for all students across the country).

- 1.3 of every 100 students with disabilities nationally was restrained or secluded.

When compared with the data from two years before (see above), it appears that—even during a time when the U.S. Department of Education was encouraging a decrease in seclusions and restraints, the actions were increasing for students with disabilities.

_ _ _ _ _

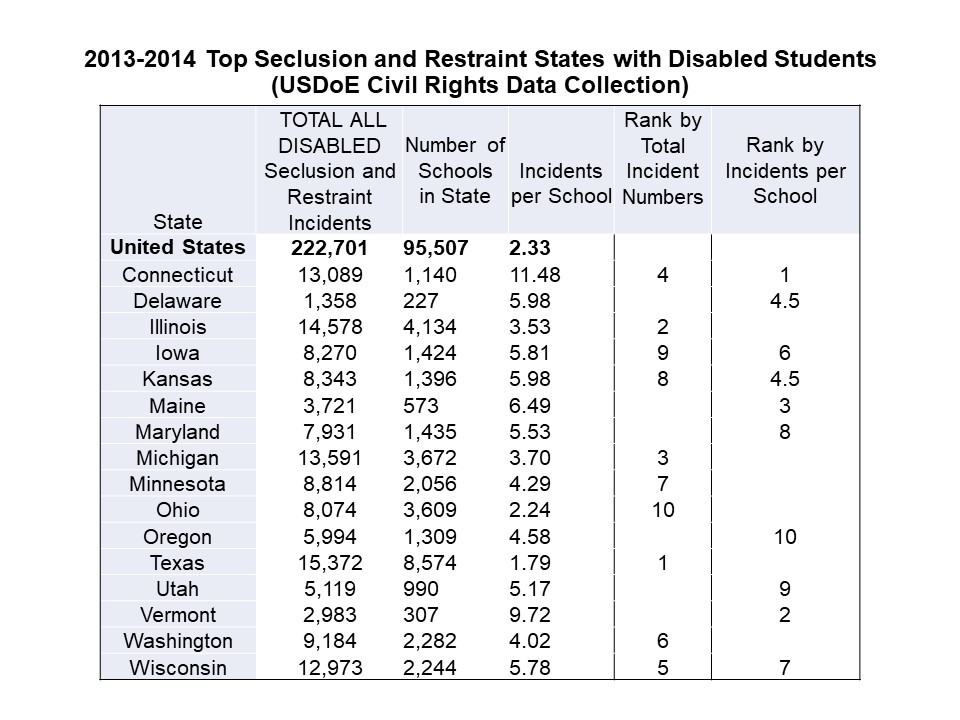

Relative to the CRDC data from the 2013-2014 school year, we pooled the reported seclusions and restraint data for all students with disabilities gathered from across the country. This pool, then, included those students receiving services under both IDEA and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. We then analyzed the data to identify (a) the “Top Ten” states that were secluding or restraining students with disabilities in sheer absolute numbers, and (b) the “Top Ten” states that were secluding or restraining students with disabilities per school in the state. While there are other ways to analyze these data, we thought that these were sufficient to make our major points.

Below is a table with the results of our analyses.

Most critically, the 2013-2014 and 2015-2016 CRDC data tell us that interventions for students with challenging behavior either are not sufficiently present or have not been successful in preventing the behaviors that eventually result in the “need” for a seclusion or restraint.

In my March 16th Blog (referenced and linked above), we discuss both the root cause analyses that are needed, and a menu of possible interventions that will help to address these gaps.

But, from a PBIS perspective, it is interesting—in the Table above—to see Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, and Oregon on the “Top Ten” lists. From my (and other national leaders') perspective(s), these are states with the some of the most well-established state PBIS networks in the country.

For example, the PBIS National TA Center has been jointly housed for many years at the University of Oregon and the University of Connecticut. And National PBIS leaders are often drawn from the state PBIS centers in Illinois, Maryland, and Michigan.

While, once again, there certainly are state-specific issues always present, one would think that these well-established PBIS state programs would be so well-established in the schools in their respective states that these states would not be listed in the Table above.

_ _ _ _ _

Indeed, the National PBIS TA Center has been involved in the issue of seclusions and restraints for (at least) almost a decade.

On April 29, 2009, the National PBIS TA Center Co-Directors published a paper, Considerations for Seclusion and Restraint Use in School‐wide Positive Behavior Supports.

In this two-page paper, which was largely a promotion for PBIS and the TA Center, it offered the following “policy” recommendations:

1. The majority of problem behaviors that are used to justify seclusion and restraint could be prevented with early identification and intensive early intervention. The need for seclusion and restraint procedures is in part a result of insufficient investment in prevention efforts.

2. Seclusion and restraint can be included as a safety response, but should not be included in a behavior support plan without a formal functional behavioral assessment (a process used to identify why the problem behavior continues to occur).

3. Seclusion and restraint should only be implemented (a) as safety measures (b) within a comprehensive behavior support plan, (c) by highly trained personnel, and (d) with public, accurate, and continuous data related to (1) fidelity of implementation and (2) impact on behavioral outcomes (both increasing desired and decreasing problem behaviors).

4. School‐wide positive behavior support may be an effective approach for (a) decreasing problem behaviors that may otherwise require seclusion and restraint, (b) improving the fidelity with which intensive individual behavior support plans are implemented, and (c) improving the maintenance of behavioral gains achieved through intensive individual support plans.

While I understand that one cannot directly “blame” the National PBIS TA Center for the current state of affairs reported in the seclusion and restraint data above . . . the PBIS framework still is the USDoE’s national framework for school behavior, and the Center has had almost ten years to impact our schools in this area.

According to the National PBIS Center’s website (as of today), there are “over 25,911 PBIS schools” in this country. . . “and counting.”

According to the National Center for Educational Statistics, in the 2015-16 school year (the most recent year with these data), there were 98,300 schools (including charter schools) in our country.

Once again, not to be unfair, but if the multi-tiered PBIS framework were being implemented effectively (according to the data immediately above) in approximately one quarter of our nation’s schools—and if the framework was positively influencing the other non-participating schools through their state departments of education (most of whom have embraced PBIS for decades). . . why are we not getting better seclusion and restraint results?

All told, it does not appear that the PBIS framework has significantly improved school discipline practices or outcomes in this area. Instead, they have been tinkering around the edges of the problem, and in some cases (see the concerns above), they have made the systemic problems worse.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

How the USDoE is Doubling Down on these Poor Results

In the Introduction to this Blog, we discussed how “doubling down” occurs in many different contexts. . . poker, politics, life, business, and within the U.S. Department of Education (USDoE).

In business, when a product or company is failing—that is, when it is not producing good quality results (such that people don’t want to buy it or invest in it), the business either folds ... or it goes back to research and development, and it re-makes itself.

In this Blog, we have presented sound and objective data and results that tell us that the USDoE’s RtI/MTSS and PBIS frameworks are not working for students, staff, and schools (SEL will be discussed below).

But rather than admitting that the frameworks are scientifically substandard and unviable, and going back to “research and development,” the USDoE has doubled down. . . multiple times . . . throwing more taxpayer money at more research in an attempt to validate their flawed frameworks.

And in these acts of doubling down (four times), the USDoE has demonstrated (at least) the appearance of a conflict of interest, and (at least) some level of fiscal irresponsibility. But no one has been there to stop it.

Here are some “Double Down Examples.”

_ _ _ _ _

Double Down #1: The National RtI Study of Grade 1 to 3 Literacy (As Described Above)

As with all stories, you have to start somewhere.

Earlier in this Blog, we presented the results (Balu, Zhu, Doolittle, Schiller, Jenkins, & Gersten, 2015) of the largest federal education study of its kind. . . a study that investigated the literacy progress of approximately 24,000 first through third grade students in 13 states.

Commissioned by the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences (IES), the study statistically compared 146 schools that had been implementing key elements from the U.S. Department of Education’s Response-to-Intervention (RtI) framework in literacy for at least three years with 100 randomly-selected comparison schools in the same 13 states, who were not implementing RtI.

While the data from the study came largely from the 2011-2012 school year, the study was awarded to a New York City-based non-profit education and social policy research organization—MDRC—on March 26, 2008, and the grant ended on March 25, 2014. The total amount of the award was $14,204,339. Yes, that’s correct: $14 million !!!

So where is the Double Down? Actually, as stated before, a story has to begin somewhere.

The primary purpose of this grant was to validate the USDoE’s first official RtI framework. . . a framework that was developed because of the reauthorization of IDEA in 2004.

With the passage of IDEA in 2004, and the USDoE’s completion of the accompanying IDEA Part B regulations in August, 2006, the USDoE now was responsible for monitoring the law’s provision that “states cannot require districts to identify SLD (Specific Learning Disability) students using a discrepancy between a student’s ability and achievement. Rather, districts are permitted to use an SLD identification process based on the student’s response to scientific, re-search-based interventions” (quoted from the Balu et. al, 2015 report).

Rather than letting districts apply the existing research and create their own response-to-intervention approaches, the USDoE (specifically, OSEP) decided that it would fashion its own framework.

Balu et al., (2015) explain how this was done:

In response to these changes, multiple organizations began to offer support and guidance to states and districts on how to design and implement an RtI framework to address academic and behavioral problems. This multiplicity resulted in a variety of approaches to implementation rather than a single model against which fidelity is measured.

The U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP), funded four national technical assistance centers to provide educators guidance in identifying valid, reliable, and diagnostically accurate tools for universal screening and progress monitoring and in identifying research-based language arts, math, and behavioral interventions.

IES, through the What Works Clearinghouse (WWC), produced the practice guide Response to Intervention in Elementary Reading derived from research evidence and experts’ recommendations. Additionally, professional organizations supported adoption and implementation of best practices. Likewise, states have undertaken activities to support RtI implementation.

From these multiple efforts to support RtI designs and implementation, a general framework emerged that is discussed in more detail later in this chapter. There is variation within this general framework, as states, districts, and schools adopting RtI brought their own perspectives and needs to the effort. One of the goals of this evaluation is to describe the differing ways that RtI was implemented in a variety of schools, rather than to assess the fidelity of implementation to a single RtI design.

_ _ _ _ _

Critically, the IES Response to Intervention in Elementary Reading (referenced above) was actually published by IES in February, 2009 as Assisting Students Struggling with Reading: Response to Intervention and Multi-Tier Intervention for Reading in the Primary Grades. A Practice Guide with Russell Gersten as the lead author.

And yet, the Balu et al. report—which was published in 2015—mis-titles the February, 2009 Practice Guide as Response to Intervention in Elementary Reading. Why this was done remains a mystery. But it can’t be a coincidence. Russell Gersten is both the last author of the 2015 report, and the first author of the 2009 IES Practice Guide.

[Fill in your favorite “conspiracy theory” here.]

Regardless, the 2009 Practice Guide became the cornerstone of OSEP’s national RtI framework, and the methodological guidance document for the Balu et al. (2015) RtI literacy study.

In fact, when you read the criteria for school inclusion in the Balu et al. Report, it is immediately apparent that, once again, this study was being conducted to validate OSEP’s national RtI framework.

Specifically, the Balu et al. (2015) Report states [see my bolded sections]:

Public elementary schools that were experienced in the implementation of RtI practices form the impact sample of schools for this evaluation.

The study research team defined a school’s experience with RtI in several ways.

First, schools had to adopt the framework by at least the 2009-10 school year, in order to have at least three years of RtI implementation at their schools at the time of site selection.

Second, by at least 2009-10, schools had to begin implementing key practices recommended in the IES Practice Guide on RtI for Elementary Reading that correspond to the key RtI practices described in Chapter 1.

Those conditions informed the following initial eligibility criteria, all of which had to be met:

- Use of three or more tiers of increasing instructional intensity to deliver reading services to students

- Assessment of all students (universal screening) at least twice a year

- Use of data for placing students in Tiers 2 or 3

- Use of progress monitoring (beyond universal screening) for students reading below grade level to determine whether intervention is working for students placed in Tier 2 or 3

In addition, for inclusion in the impact analysis, schools needed to meet the following requirements: (1) use a quantitative data-based rating system in fall 2011-12 to identify students in need of more intense reading assistance, (2) meet thresholds for the number of students in each grade and in each tier of instruction, and (3) agree to meet data collection requirements for the evaluation.

Schools also had to be located in states that administered Grade 3 state testing of students in spring 2012.

_ _ _ _ _

None of this is illegal.

But clearly, the USDoE and OSEP were using public funds to validate and begin the “branding” process of its own RtI framework.

They could have just as easily taken the $14 million and given five grants to five different viable RtI models and research groups, and let them independently (in controlled methodological ways) identify “the best” approach(es) based on student-generated outcomes.

But, the USDoE and OSEP did not do this. They went “all-in”. . . doubling down on one (albeit large, historical) study, with an implicit attitude of “we know best.”

And so, the next double down came after the Balu et al. (2015) study showed such “disappointing” results.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Double Down #2: Impact Evaluation Training in Multi-Tiered Systems of Support for Reading (MTSS-R) in Early Elementary School

In response to the disappointing Balu et al. (2015), the USDoE’s Institute of Education Sciences (IES) released a Request for Proposals in the Spring/early Summer of 2018 for the grant program titled above. The grant was awarded in the late summer to the American Institutes for Research (AIR), another large, non-profit educational research company based in Washington, D.C.

Parenthetically, AIR (and a number of its competitors) receive millions of dollars in USDoE grants each year. For example, an August 1, 2018 AIR press released announced AIR’s receipt of eight IES research grants (not including the one above) totaling $19,491,497.

In addition, AIR current runs a number of National TA Centers for the USDoE and/or IES. Among them are the Center on Response to Intervention, and the National Center on Intensive Intervention.

The Multi-Tiered Systems of Support for Reading (MTSS-R) grant in question here will run from September, 2018 through August, 2024 to the tune of $17,281,100 !!!

[If you’re keeping score here, folks, that’s $36,772,597 to AIR solely from the USDoE’s IES unit in just 2018 alone! And I really did not research all of the grants awarded to AIR. . . so there may be more.]

Besides the involvement of your tax dollars, this AIR study is basically designed as an attempt to revalidate the USDoE’s MTSS-R framework that is simply the updated, but rebranded USDoE RtI framework (that did not produce positive results as in Balu et al. above).

To do this, AIR will subcontract the actual research to another group that will actually conduct the study.

But the point here is: that the USDoE is doubling down on validating its RtI/MTSS-R framework to the tune of $19 million in taxpayer money.

Below is the proof of this assertion from AIR’s recent Request for Proposals (RFP). . .focused on hiring the research group to actually complete the study. This RFP just closed on March 4, 2019 (a few weeks ago), and will be awarded in late April.

More critical, here, is that the research design and reading approaches that the “winning” subcontractor must use is the refurbished USDoE RtI framework, now rebranded as MTSS-R. Moreover, the study is a virtual “re-do” of the Balu et al. (2015) study—just under more controlled conditions.

The American Institutes for Research (AIR), in collaboration with Instructional Research Group (IRG) and School Readiness Consulting (SRC), issues this Request for Proposals (RFP) seeking qualified entities to provide intensive professional development (PD) on the implementation of a comprehensive multi-tiered system of support for reading (MTSS-R) model.

The selected provider will collaborate with the study team on a large-scale, randomized controlled trial of MTSS-R in Grades 1 and 2 for the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education(ED). The randomized controlled trial will test a comprehensive MTSS-R model involving four components: (a) differentiated and explicit Tier I instruction for all students, (b) evidence-based Tier II intervention for students identified as being at risk for reading difficulty, (c) screening of all students and progress monitoring of students identified as being at-risk, and (d) the MTSS-R infrastructure necessary for schoolwide implementation, including the staff and procedures necessary to support MTSS-R implementation.

The study will take place in approximately 10 geographically diverse school districts. In each district, approximately five elementary schools will be randomly assigned to receive professional development (PD) and implement MTSS-R—a total of 50 schools. The selected provider will deliver PD to school staff and a district-based coach in all selected districts. The PD will target a school-level team that will be responsible for MTSS-R implementation, Grade 1 and 2 teachers, special educators, interventionists, the MTSS-R team, and district-based MTSS-R coaches. The goal of the PD is to build school capacity for implementation of the MTSS-R model in Grades 1 and 2 with fidelity.

We seek proposals that operationalize the MTSS-R model we describe in this RFP. Providers must propose a detailed implementation plan that aligns with the MTSS-R model described in the RFP. The plan should include a detailed description of the MTSS-R components and how these components interact to form a cohesive system. In addition, we seek a detailed description of the PD necessary for schools to implement the model. Providers must propose PD that supports the implementation of the detailed MTSS-R plan proposed by the provider with fidelity.

The goal of the study is to implement a comprehensive MTSS-R model with fidelity and evaluate its impact on students’ reading achievement. Studies have demonstrated promise for individual components of MTSS-R, such as the use of supplemental supports. But there is little rigorous evidence on the effectiveness of a comprehensive MTSS-R model.

The MTSS-R model that will be evaluated includes four core components:

Tier I Instruction. Tier I refers to systematic core reading instruction using evidence-based practices, including differentiated and explicit instruction for all students.

Tier II Intervention. Tier II is the provision of supplemental evidence-based program(s) focused on foundational reading skills and using high-leverage instructional practices (e.g., modeling, multiple opportunities to respond, feedback) for students identified as at-risk of reading difficulty.

Screening and Progress Monitoring. The MTSS-R model includes regular use of validated assessment tools to screen all students for reading difficulty and monitor the progress of students identified as being at-risk to guide student placement in Tier II intervention.

Infrastructure. The infrastructure includes a school-based team that meets regularly to lead and coordinate MTSS-R implementation and a district-based MTSS-R coach who supports school staff to implement MTSS-R with fidelity.

The offeror must be able to provide training and support for implementation of all four core components to approximately 50 schools in 10 districts throughout the United States for 2 years. Support must include readiness activities in spring 2020, initial content trainings in summer 2020, booster trainings in summer 2021, and implementation supports across school years 2020–21 and 2021–22.

ED is funding the study through a contract with AIR. AIR will fund the training through a subcontract to the selected provider and will manage this subcontract. The subcontract will be structured as firm fixed-price, with payments tied to acceptance of deliverables. The maximum funding available for the provider subcontract is $2,500,000.

Enough said.

_ _ _ _ _

Double Down #3: USDoE/IES Study on the Efficacy of PBIS

Earlier in this Blog, we described the results of the qualitative study of the PBIS framework as developed and implemented through the National PBIS TA Center. The circa 2012-2013 study, commissioned by the USDoE’s Institute of Education Science (IES), was completed by a joint research team from the University of South Carolina’s School Mental Health Team, Tanglewood Research Inc., and Research Triangle Institute (RTI) International.

As we noted the study was “hidden” as an Appendix to a new RFP designed to address the “negative” results by investigating the PBIS framework through more controlled research.

[CLICK HERE for the RFP Announcement and Appendices]

The Double Down here is that, once again, the USDoE, OSEP, and the IES threw additional grant money to fund a PBIS framework research study because its own evaluation of the framework showed significant gaps in its processes.

So. . . here’s the kicker.

The grant to conduct the study of the PBIS framework. . .

[CLICK HERE for the Award Announcement]

was awarded jointly to MDRC (of Balu et al., 2015 fame), and AIR (of MTSS-R fame) from November, 2013 through August, 2020 to the tune of $23,796,966 in taxpayer money!!!

And rather than calling it a “PBIS” study, they once again rebranded PBIS—now calling it the Multi-tiered Systems of Support for Behavior (MTSS-B).

And if you want to know the research design for the study, all you need to do is take the Literacy part out of the MTSS-R description in the Double Down #2 section above, and substitute behavior and PBIS.

_ _ _ _ _

But one more issue occurred here.

As in the MTSS-R grant (see above), MDRC and AIR similarly awarded a subgrant for the completion of the actual PBIS research.

This subgrant was awarded to the Center for Social Behavior Support (CSBS), which is a collaboration between The Illinois-Midwest PBIS Network at the School Association for Special Education in DuPage, Illinois (SASED), and the PBIS Regional Training and Technical Assistance Center at Sheppard Pratt, in Maryland.

But who was on the Technical Working Group that in February, 2013 designed the MTSS-Behavior study that was awarded in September, 2014 to the Illinois-PBIS and Maryland-PBIS lead state units?

[CLICK HERE] and look see Page 3 of this SWPBS Summary of Expert Panel Meeting and Follow-Up Discussion]

None other than the following individuals (see the two highlighted below):

U.S. Department of Education Staff

Lauren Angelo (Institute of Education Sciences)

Jonathan Jacobson (Institute of Education Sciences)

Audrey Pendleton (Institute of Education Sciences)

Renee Bradley (Office of Special Education Programs)

_ _ _ _ _

William B. Hansen (Tanglewood Research)

Linda Dusenbury (Tanglewood Research)

Dana Bishop (Tanglewood Research)

Mark Weist (University of South Carolina)

Joni W. Splett (University of South Carolina)

Suyapa Silvia (RTI International)

Jonathan Blitstein (RTI International)

_ _ _ _ _

Technical Working Group (TWG) Members

Catherine Bradshaw (Johns Hopkins School of Public Health)

Michele Capio (PBIS Illinois)

Lucille Eber (PBIS Illinois)

Brian R. Flay (Oregon State University)

Larry Hedges (Northwestern University)

Jeanne Poduska (American Institutes for Research)

Sara Rimm-Kaufman (University of Virginia)

George Sugai (University of Connecticut)

Bridget Walker (Seattle University)

Karen Weston (Columbia College)

_ _ _ _ _

Critically, it should be noted that there were two individuals(Michele Capio and Lucille Eber) who were on the Technical Working Group in 2013 from the same Illinois-PBIS officethat eventually won the MTSS-B subcontract from MDRC and AIR in 2014.

From my perspective, the involvement of these two individual in 2013 could have given the Illinois-PBIS group an unfair competitive advantage in writing for the aforementioned RFP.

Thus, a clear conflict of interest is present here, and the Illinois-PBIS group should have been disqualified from writing for (much less being awarded) the MTSS-B subcontract/grant.

I personally filed a complaint with the Inspector General’s Office within the U.S. Department of Education on this issue.

My petition was denied.

So. . . not only did the USDoE double down by awarding a $23 million dollar grant to validate its own PBIS (read MTSS-B) framework, but it allowed a subcontract within that grant to be awarded improperly.

_ _ _ _ _

Double Down #4: Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)

Over the past year or two, it is nearly impossible to avoid recognizing that social-emotional learning (SEL) has taken over education.

[CLICK HERE for my November 10, 2018 Blog on “The SEL-ing of Social-Emotional Learning: Education’s Newest Bandwagon. . . Science-to-Practice Goals, Flaws, and Cautions (Part II)]

[CLICK HERE for Part I that details an SEL History]

Indeed, McGraw-Hill’s recently published its Education 2018 Social and Emotional Learning Report where it surveyed over 1,000 administrators, teachers, and parents. All three groups surveyed said that they believe that social and emotional learning is just as important as academic learning. More specifically, social and emotional learning was endorsed by 96% of administrators, 93% of teachers, and 81% of parents.

The Report also noted that:

- Nearly two-thirds of the educators surveyed said their school is in the process of implementing a school-wide strategic SEL plan.

- Three-quarters of teachers surveyed say they are teaching SEL in their classrooms, and 74% of teachers say they are devoting more time to teaching SEL today than five years ago.

- Teachers and administrators said that social and emotional learning programs would positively impact school safety (76% and 66%, respectively), lack of student motivation and engagement (75% and 66%), and school climate (71% and 69%).

_ _ _ _ _

Significantly, when you look at the national media attention recently given to SEL versus PBIS, SEL wins hands down. SEL has garnered the “lion’s share” of the attention. Indeed, it is dominating “the market.”

And I am guessing that the USDoE is concerned about this—given their advocacy and funding of PBIS/MTSS-B.

And if I am correct, then the following double-down follows.

In May, 2018, the USDoE’s Office of Elementary and Secondary Education initiated an RFP for the Center to Improve Social and Emotional Learning and School Safety.

On November 5, 2018, the following Press Release was posted by WestEd—yet another non-profit educational research, development, and service agency that receives millions of grant dollars from the USDoE each year.

The Press Release stated:

WestEd Wins New Federal Grant to Lead the Center to Improve Social and Emotional Learning and School Safety

WestEd is recipient of a U.S. Department of Education grant to lead the Center to Improve Social and Emotional Learning and School Safety. The RAND Corporation, Council of Chief State School Officers, and Transforming Education will serve as partners in the work.

The Center expands the knowledge and capacity of educators and system leaders to integrate evidence-based social and emotional learning (SEL) and school safety practices and programs with academic learning in order to promote success for every student in college, career, and beyond.

To serve the needs of state education agencies (SEAs) and local education agencies (LEAs), the Center will adopt a multi-faceted approach to its work. With clear knowledge of effective, evidence-based SEL and school safety programs and practices, the Center will serve as:

A trusted advisor to SEAs and LEAs as they integrate effective and sustainable new practices with their existing academic models; and

A clearinghouse to match effective, evidence-based approaches with the distinct needs of children, educators, and their school communities.

WestEd and the agency’s partners will support education leaders across the country with attending to the needs of the whole child — ensuring that every student receives an education that integrates programs and practices focused on SEL, school climate, and safety, alongside other aspects of schooling.

My read on the rationale behind this USDoE grant is that “If you can’t beat ‘em, you join ‘em. . . so that eventually, you can beat 'em."

I believe that the USDoE was increasingly concerned that SEL was going to (if not, it had already succeeded in) eclipsing PBIS/MTSS-B. So, the USDoE created and funded this Center in an attempt (a) to reclaim the bully pulpit in this area, and (b) to re-establish its “voice” and influence in this area (over the independent Collaborative for Academic, Social, Emotional Learning).

Thus, a fourth Double-Down example. . . . to the tune of $1 million dollars per year over the next five years.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

While I have presented objective data throughout this Blog, I am not an objective party. These RtI, PBIS, MTSS-R, MTSS-B, and SEL areas are where I have spent much of my research, writing, consulting, and professional career.

And, I have had a front-row seat in many of the events that I have described above.

The bottom line in all of this are the students, staff, and schools that need effective, objective, and expert science-to-practice services, supports, strategies, and interventions. . . and who are not getting them because of political, financial, and personal agendas.

I don’t expect the USDoE to stop funding professionals who have different ideas about how to best serve our students.

But I do expect the staff within the USDoE to be fair about getting this done.

And I believe that the history, facts, decisions, and actions that I have described above suggest (if not prove) that fairness has been compromised—at some points in time—within the USDoE and its different offices—including its own Office of the Inspector General.

_ _ _ _ _

As always, I look forward to your thoughts and comments.

I am always available to provide a free hour of telephone consultation if you want to discuss your student, school, or district need. Feel free to contact me at any time if there is anything that I can do for you, or your students, colleagues, staff, schools, districts, or community agencies.

Best,