Taking a Hard Look at Our Practices, Our Interactions, and Ourselves

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction: Back to the Future

Almost immediately after writing Part I of this Blog series a few weeks ago, two additional reports (see below) were published providing additional, persistent documentation regarding how African-American students and Students with Disabilities (SWD) continue to be discriminated against in our schools relative to discipline, office discipline referrals, and school suspensions.

One of the themes in Part I was that the policy changes that have occurred over the past few years to address this decades-long discrimination have not worked.

For example, the districts that have adapted their policies such that African-American students and SWDs at certain grade levels cannot be suspended for any disciplinary infraction (a) have not decreased the disproportionate referrals of these students to their principals’ offices; and (b) have delayed the professional development needed by their instructional staffs, and the services and supports needed by their students.

_ _ _ _ _

A second Part I theme was that educators need to question the knowledge, skill, and ability of the federally-funded National Technical Assistance Centers (TACs) to truly assist in this area. These TACs have been “assisting” states, districts, and schools—depending on the TAC—from five to over 20 years and, based on the continued disproportionality data, their track record is not good.

This includes such TA Centers as: the National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments; National Student Attendance, Engagement, and Success Center; National Technical Assistance Center for the Education of Neglected or Delinquent Children and Youth; Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) Technical Assistance Center; Center for School Mental Health; and the Now Is the Time Technical Assistance Center.

Related to this discussion was the warning to districts and schools to beware of the “If it’s Free, It’s for Me’” perspective.

That is, just because the National TACs provide many of their services for “free” (actually, using our tax dollars), if their services are not successful in solving the targeted problems—or, significantly, if they create more staff and student resistance in their wake—then there is a cost to engaging them. And it is a negative cost that affects people’s lives.

Blog Part I also critiqued and expressed concerns regarding how educators are using Hattie’s meta-analytic research, as well as why they are using approaches that have research-to-practice flaws: for example, PBIS, SEL, Character Education, Restorative Justice

_ _ _ _ _

A last Part I theme is incapsulated in the following statement:

And it is not that bias and prejudice against, and sometimes fear of, African-American students are not some of the issues at-hand. But the primary reasons why we are not progressing in this area involve knowledge and training, resources and strategies, and consultation and accountability.

Indeed, during the past ten-plus years of trying to systemically decrease disproportionality in schools, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified the root causes of the students’ challenging behaviors, and we have not linked these root causes to strategically-applied multi-tiered science-to-practice strategies and interventions.

Moreover, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified and addressed the root causes of staff members’ interactions and reactions with African-American students, boys, and students with disabilities. . . reactions that, at times, are the reasons for some disproportionate Office Discipline Referrals (when compared with the other groups in the Figures above).

And, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified and addressed the root causes of administrators’ disproportionate decisions with these students as they relate to suspensions, expulsions, law enforcement involvement, and referrals to alternative school programs.

Instead, we have been tinkering around the edges—and in some cases, we have made the systemic problem worse.

_ _ _ _ _

If you missed it, Part I of this Blog series began by analyzing a study released by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) on April 4th, K-12 Education: Discipline Disparities for Black Students, Boys, and Students with Disabilities.

[CLICK HERE for Blog Part I]

[CLICK HERE for Original GAO Study]

The Executive Summary of the Study stated:

Black students, boys, and students with disabilities were disproportionately disciplined (e.g., suspensions and expulsions) in K-12 public schools, according to GAO’s analysis of Department of Education national civil rights data for school year 2013-14, the most recent available. These disparities were widespread and persisted regardless of the type of disciplinary action, level of school poverty, or type of public school attended. For example, Black students accounted for 15.5% of all public school students, but represented about 39% of students suspended from school—an overrepresentation of about 23 percentage points (see Figures below).

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

The Two Newest Reports on Disproportionality

While the real purpose of this Blog (Part II) is to provide solutions to this problem, let’s quickly discuss the “old news” of these two new Reports.

U.S. Office of Civil Rights 2015-16 Civil Rights Data Collection

[CLICK HERE for Resource]

On April 24, 2018, the U.S. Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights (OCR) released the 2015-16 Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC). This actually is a comprehensive, interactive data-base of information (rather than a “report”) that comes from 17,300 public school districts and 96,400 public schools and educational programs from across the country.

In the area of School Climate and Safety, the OCR used the CRDC data to produce a separate “data brief” to highlight how districts and schools are faring in this area (as of the 2015-16 school year).

[CLICK HERE for this Briefing Report]

Relative to disproportionality, the Report revealed that, while U.S. schools are suspending fewer students, African-American students continue to receive disproportionately more suspensions.

Indeed, while schools suspended 2.7 million students out of school in 2015-16 (roughly 100,000 fewer than in 2013-14), African-American boys made up 25% and African-American girls made up 14% of those suspensions, respectively. In addition, African-American students accounted for nearly a third of all students arrested at school or referred to law enforcement.

This is when African-American students only made up approximately 16% of the total student population (8% for African-American boys versus girls, respectively).

For Students with Disabilities (SWDs), 26% of them received at least one suspension during the 2015-16 school year, even though they represented only 12% of all students enrolled.

These suspension rates reflect the same gaps, for African-American and SWDs, as five years ago.

_ _ _ _ _

The “Disabling Punishment” Report.

[CLICK HERE for Resource]

Also late last month, a study was released jointly by the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the UCLA Civil Rights Project, and the Houston Institute for Race and Justice: Disabling Punishment: The Need for Remedies to the Disparate Loss of Instruction Experienced by Black Students with Disabilities.

This Report analyzed national data regarding the amount of classroom time lost—due to office discipline referrals and, especially, suspensions—for SWDs from different racial groups, as well as for students without disabilities.

The study found that, while SWDs of all races received higher rates of discipline than non-disabled students, there were significant gaps between African-American SWDs and white SWDs. Specifically, in both the 2014-15 and 2015-16 school years, African-American SWDs lost roughly three times more instructional days due to disciplinary referrals, than their white SWD peers.

For example, during the 2015-16 school year, for every 100 students with special needs, African-American SWDs were out of the classroom due to school suspensions for 121 days on average as compared with 43 lost school days for white SWDs.

Taking the two reports above together, African-American and SWDs are disproportionately missing school—and needed academic instruction—when compared with students from other racial and cultural backgrounds. Moreover, African-American SWDs are additionally missing disproportionately more time than their white SWD peers.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Why Disproportionality Outcomes Haven’t Changed

In Blog Part I, we reviewed six primary flaws that explain why most of the disproportionality “efforts” to date have not worked:

Flaw #1. Legislatures (and other “leaders”) are trying to change practices through policies.

Flaw #2. State Departments of Education (and other “leaders”) are promoting one-size-fits-all programs with “scientific” foundations that do not exist or are flawed.

Flaw #3. Districts and schools are implementing disproportionality “solutions” (Frameworks) that target conceptual constructs rather than teaching social, emotional, and behavioral skills.

Flaw #4. Districts and Schools are not recognizing that Classroom Management and Teacher Training, Supervision, and Evaluation are Keys to Decreasing Disproportionality.

Flaw #5. Schools and Staff are trying to motivate students to change their behavior when they have not learned, mastered, or cannot apply the social, emotional, and behavioral skills needed to succeed.

Flaw #6. Districts, Schools, and Staff do not have the knowledge, skills, and resources needed to implement the multi-tiered (prevention, strategic intervention, intensive need/crisis management) social, emotional, and/or behavioral services, supports, and interventions needed by students.

[CLICK HERE for Blog Part I]

By understanding these flaws, districts and schools can evaluate their current effective school and schooling, and school discipline and classroom management practices—applying them to students from minority backgrounds and students with disabilities.

The ultimate point here is this:

During the past ten-plus years of trying to systemically decrease disproportionality in schools, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified the root causes of the students’ challenging behaviors, and we have not linked these root causes to strategically-applied multi-tiered science-to-practice strategies and interventions that are effectively and equitably used by teachers and administrators.

Moreover, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified and addressed the root causes of staff members’ interactions and reactions with African-American students, boys, and students with disabilities. . . reactions that, at times, are the reasons for some disproportionate Office Discipline Referrals (when compared with the other groups in the Figures above).

And, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified and addressed the root causes of administrators’ disproportionate decisions with these students as they relate to suspensions, expulsions, law enforcement involvement, and referrals to alternative school programs.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Solving the Disproportionality Dilemma

In order to establish effective, multi-tiered systems that address disproportionality, we need to strategically implement effective school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management systems, strategies, and (as needed) strategic and intensive interventions.

We have discussed the science-to-practice components needed many times in past Blogs. The ultimate goal here, for students from minority backgrounds and SWDs (although the goal is the same for all students), is for these students to learn, master, and be able to apply—from preschool through high school—social, emotional, and behavioral self-management skills.

These interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control and coping skills are delivered through five interdependent components. As some students need more strategic and/or intensive services, supports, strategies, or interventions to attain the “ultimate goal,” these components must be available along a multi-tiered continuum.

The Five Needed Science-to-Practice Components

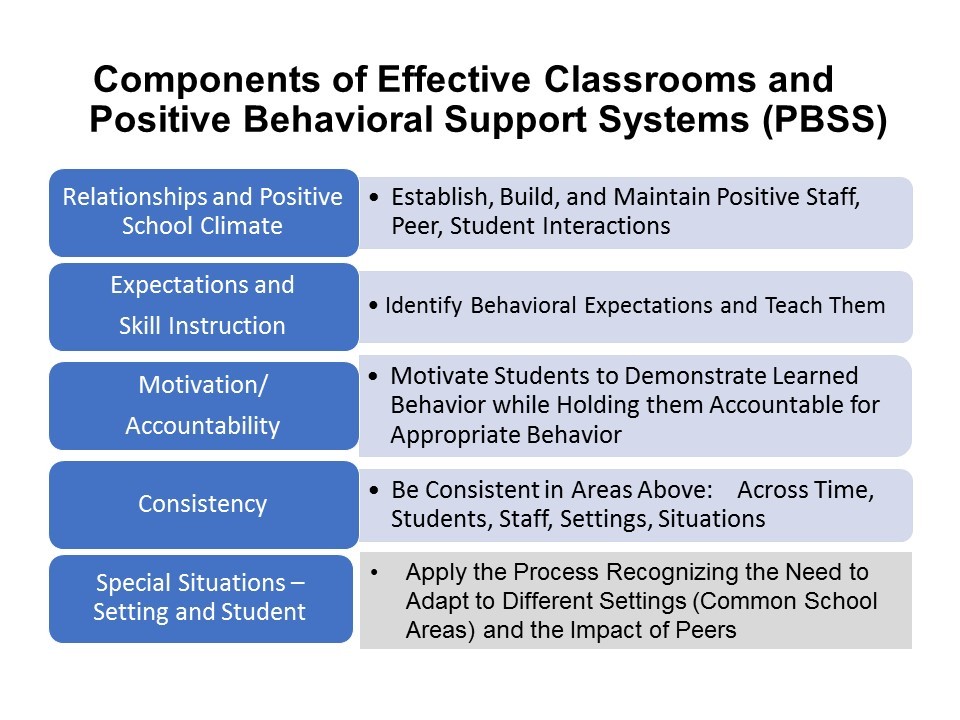

The five interdependent components (see the Figure below) needed to help minority and SWDs to realize social, emotional, and behavioral self-management are:

* Positive Relationships and School/Classroom Climate

* Positive Behavioral Expectations and Skills Instruction

* Student Motivation and Accountability

* Consistency

* Implementation and Application Across All Settings and All Peer Groups

From: Knoff, H.M. (2014). School Discipline, Classroom Management, and Student Self-Management: A Positive Behavioral Support Implementation Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

CLICK HERE for more information.

While I have discussed these components in past Blogs, so that readers do not have to “jump back” to these Blogs, I will briefly describe the five components below—applied to minority students and SWDs.

Positive Relationships and School/Classroom Climate

Effective schools work consciously, planfully, and on an on-going basis to develop, reinforce, and sustain positive and productive relationships so that their cross-school and in-classroom climates mirror these relationships.

Critically, however, these relationships include the following: Students to Students, Students to Staff, Staff to Staff, Students to Parents, and Staff to Parents.

For minority students and SWDs, this involves understanding them, their backgrounds, their “growing up” histories, their strengths and weaknesses, and their “personal stories” on a broad-based, but also an individual, level.

For minority students, this includes understanding their racial and cultural backgrounds, but being careful not to stereotype these backgrounds such that these students are not seen as individuals.

For SWD, this includes understanding them past the “labels of their disabilities”—that is, understanding how their abilities and disabilities merge to reflect who they are and what they do physically, emotionally, attitudinally and attributionally, and behaviorally.

All of this needs to be done by all of the adults across a school, but the adults need to involve and engage the different peer groups in a school to do the same things.

_ _ _ _ _

Positive Behavioral Expectations and Skills Instruction

Minority students and SWDs—from preschool through high school—need to be taught (just like an academic skill) the explicit social, emotional, and behavioral expectations in the classrooms and across the common areas of the school. These expectations need to be communicated in a prosocial way as “what they need to do,” rather than in a negative, deficit-focused way as “what they do not need to (or should not) do.”

Indeed, teachers and administrators will have more success teaching and telling students to (a) walk down the hallway (rather than “Do not run”); (b) raise your hand and wait to be called on (rather than “Don’t blurt out answers”); (c) accept a consequence (rather than “Don’t roll your eyes and give me attitude”).

In addition, these expectations need to be behaviorally specific—that is, we need to describe exactly what we want the students to do (e.g., in the hallways, bathrooms, cafeteria, and on the bus).

Indeed, it is not instructionally helpful to talk in constructs—telling students that they need to be “Respectful, Responsible, Polite, Safe, and Trustworthy.” This is because each of these constructs involve a wide range of behaviors. At the elementary school level, students really do not functionally or behaviorally understand these higher-ordered thinking constructs. At the secondary level, students may interpret these constructs (and their many inherent behaviors) differently than staff.

Thus, and as above, we need to teacher these (all) students the behaviors that we want them to demonstrate. Critically, this is done by teaching these students—from preschool through high school—social skills and behaviors (just like we teach a basketball the different plays in our offensive playbook).

This instruction is done by the general education classroom teachers.

In this way, minority students and SWDs learn to respond to their classroom teachers (rather than a school counselor), the social skills become an inherent part of classroom management and student self-management, and inappropriate student behavior decreases—because students know and can do the appropriate behavior.

At the same time, especially for SWDs, the instruction may need to be modified or accommodated to their disabilities, and the instructional processes may need to be co-taught by both general education and special education staff.

Finally, the teaching approach required when we teach social skills to students must be grounded in social learning theory. Specifically, we need to teach students the social skill behaviors step-by-step, demonstrate the steps to them, give students opportunities to practice with explicit feedback, and then to help students to apply (or transfer) their new skills to “real-world” situations.

[For a free Overview of this Process, CLICK HERE

and look for the document The Stop & Think Social Skills Program: Exploring Its Research Base and Rationale]

_ _ _ _ _

Student Motivation and Accountability

For the skill instruction described above to “work,” minority students and SWDs need to be motivated to and held accountable for demonstrating positive and effective social, emotional, and behavioral skills.

Scientifically, however, motivation is based on two component parts: Incentives and Consequences. But to work, these incentives and consequences must be meaningful and powerfulto the students (not just to the adults in a school).

That is, too often schools create “motivational programs” for students that involve incentives and consequences that the students couldn’t care less about. Thus, it looks good “on paper,” but it holds no weight in reality—at least from the students’ perspectives.

But this is not about programs, it is about effective practices. And in order to decrease or eliminate disproportionality, while increasing effective classroom management and student self-management practices, teachers need a classroom discipline “road map.”

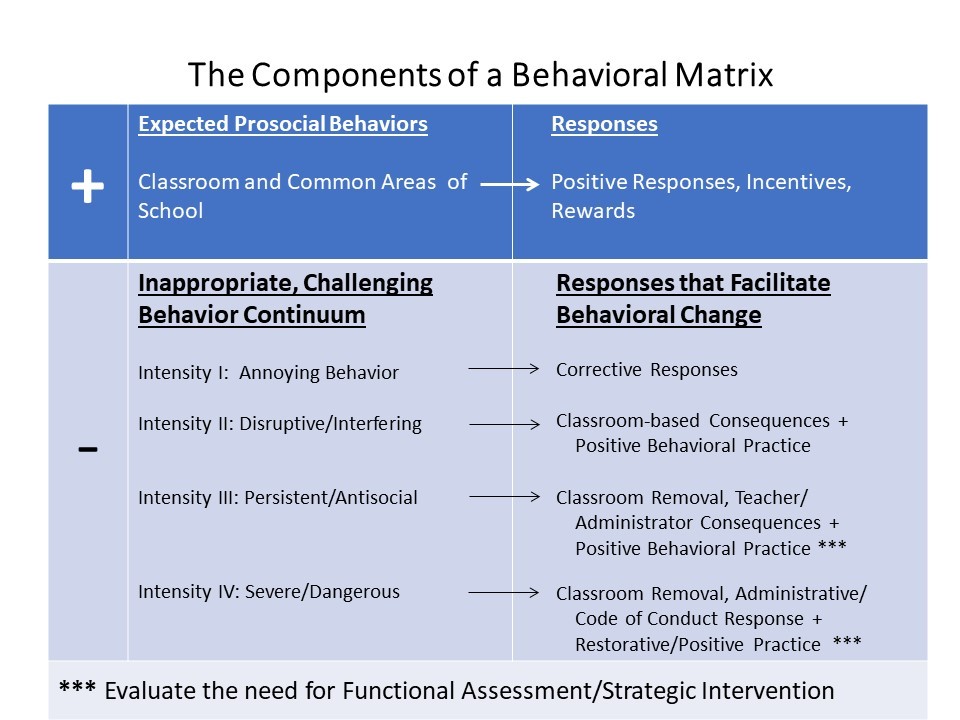

For us, we call this road map a Behavioral Matrix, and we continually work with schools nationwide to help them to develop their own Matrix—sensitive to their staff and students.

The Behavioral Matrix is the “anchor” to a school’s behavioral accountability and progressive school discipline system. At the Elementary School level, there typically is a Behavioral Matrix at each grade level because of the developmental differences across prekindergarten through (typically) Grade 5 students. At the Secondary levels, there typically is a school-wide Matrix—although at times, we create Grade 6 and Grade 9 matrices because these students are often entering the Middle School and High School levels, respectively, for the first time.

Every Behavioral Matrix has components that address appropriate versus inappropriate behavior, respectively (see the Figure below). The first two parts of the Matrix specify (a) the behavioral expectations in the classroom connected (b) with positive responses, motivating incentives, and periodic rewards.

The third and fourth parts identify four progressive “Intensity Levels” of inappropriate behavior, connected with corresponding corrective responses, in and out-of-classroom consequences, and administrative actions. These components make students aware of how inappropriate behavior will be addressed when it occurs— thereby (a) motivating student to avoid these responses by demonstrating appropriate behavior, or (b) preparing students for the consequences or administrative responses if they choose to demonstrate inappropriate behavior.

The four Intensity Levels are briefly defined as follows:

Intensity I (Annoying) Behavior: Behaviors in the classroom that are annoying or that mildly interrupt classroom instruction or student attention and engagement. Teachers can handle these behaviors with a minimum of interaction by using a corrective response (e.g., a non-verbal prompt or cue, physical proximity, a social skills prompt, reinforcing nearby students’ appropriate behavior).

Intensity II (Disruptive or Interfering) Behavior: Behavior problems in the classroom that occur more frequently, for longer periods of time, or to the degree that they disrupt classroom instruction and/or interfere with student attention and engagement. Teachers handle these behaviors with a corrective response, and a classroom-based consequence (e.g., loss of student points or privileges, a classroom time-out, a note or call home, completion by the student of a behavior change plan).

Intensity III (Persistent or Antisocial) Behavior: Behavior problems in the classroom that significantly (as a single incident) or persistently (increasing in severity over time) disrupt classroom instruction or engagement, or that involve antisocial interactions toward adults or peers. These inappropriate behaviors require some type of out-of-classroom response (e.g., time-out in another teacher’s classroom, removal to an in-school suspension or “student accountability room,” an office discipline referral), followed up by a pay-back response (e.g., an apology, cleaning up/repairing damaged property or a messed-up classroom, community service), a consequence and, if needed, an intervention to eliminate a reoccurrence of the problem behavior.

Intensity IV (Severe or Dangerous) Behavior: Extremely antisocial, damaging, and/or dangerous behaviors, on a physical, social, or emotional level, that typically are cited and addressed in a District’s Student Code of Conduct handbook. These inappropriate behaviors require an immediate administrative referral and response (e.g., a parent conference, suspension, or expulsion), followed by a pay-back response, and an intervention to eliminate a reoccurrence of the problem behavior.

Critically, when students and staff are taught and begin to internalize the Behavioral Matrix and its processes, student motivation and self-management increases, as does effective classroom management and teacher consistency.

Relative to disproportionality, when teachers consistently use the Intensity I, II, and III areas of the Matrix for all students, disproportionality is decreased or eliminated. Often, this occurs because the Matrix specifically discriminates between annoying (Intensity I) and disruptive behavior in the classroom (Intensity II)—explicitly the identifying different responses that are differentially appropriate for them.

When Administrators additionally hold teachers accountable for using the Matrix appropriately and consistently for all students, once again, disproportionality is effectively addressed.

For example, when minority students or SWDs are “sent to the Office” for Intensity I or II behaviors, administrators need to directly question and correct the classroom teacher for these “science-to-practice errors”—errors that not only represent disproportionality, but that are going to undermine the teacher’s classroom management and relationship with that student.

_ _ _ _ _

Beyond this, when implementing the Behavioral Matrix, schools need to remember to recognize, engage, and activate different peer groups in their motivational approaches.

This is because, at times, some peers actually undermine classroom management and student self-management by socially influencing and reinforcing certain students' inappropriate behavior (for example, in the classroom or in the common areas of the school). When this occurs, these students often behave “appropriately” with their classroom teachers only when they alone with them (or, at least, when in the absence of the “pressuring” peer group). When the “negative” peer group is present, however, these same students behave inappropriately with adults because peer approval or disapproval is more reinforcing, powerful, or meaningful than what the teacher may do per the Matrix.

Critically, this peer pressure dynamic is present very often with minority students and SWDs.

_ _ _ _ _

Ultimately, relative to this component, the goal is self-motivation and self-accountability. When this occurs, we have a higher probability that minority students and SWDs will (a) demonstrate more appropriate behavior the first time, (b) quickly correct their inappropriate behavior in the face of the meaningful consequences and positive practice “re-education” delivered, and/or (c) respond to the Behavioral Matrix administrative responses delivered in the Principal’s Office by changing their behavior.

Relative to this latter area, one of the essential aspects is how schools and staff discrimination between “disciplinary” problems and “behavioral” problems.

This was discussed in Part I of this Blog series under Flaw #6:

Disproportionate disciplinary referrals and actions (like suspensions) for minority (largely, African-American) students and students with disabilities occur due to a combination of (a) district policy and procedures; (b) teacher and administrator interactions, reactions, and decisions; and (c) student behavior.

In the latter area, administrators and staff need to discriminate between inappropriate student behavior that is disciplinary in nature versus due to psychoeducational factors. While this is not always easy, and both elements could be present, this discrimination is critical to coming up with a plan to change students’ inappropriate behavior—the ultimate goal of any action or response.

Quite simply, a discipline problem typically occurs where a student can demonstrate appropriate behavior but chooses not to.

In other words, the student is somehow internally motivated (e.g., due to needs related to attention, control, revenge, anger) to “make a bad choice,” or is externally motivated (e.g., by peer pressure or reinforcement, to escape from failure or frustration) to make the same bad choice.

From a cognitive-behavioral psychology perspective, teachers or administrators are “banking” on the fact that their disciplinary consequences are powerful enough to motivate a student to “make a good choice” the next time, and that the resulting positive rewards will maintain the appropriate behavior.

Thus, disciplinary actions need to have flexible and available consequences that are meaningful and powerful enough to motivate behavioral change.

At the same time, school principals still need to have “administrative actions” available when student behavior is grossly antisocial or dangerous. Critically, these administrative actions rarely motivate students to change their behavior.

_ _ _ _ _

In contrast, a psychoeducational problem typically occurs when a student has not learned or learned to apply interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention or resolution, or emotional control and coping skills. These are skill deficits, and they require skill instruction to facilitate change.

In fact, for some students, some of these skill deficits are related to fairly significant social, emotional, behavioral, or mental health issues . . . issues that require strategic or intensive intervention—including cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Critically, you can’t motivate a student out of a skill deficit. That is, no amount of consequences or administrative actions will change skill these deficits—they require instruction and/or psychological intervention.

_ _ _ _ _

In order to discriminate between disciplinary- and psychoeducationally-based behavioral problems, administrators may need to ask relevant members of their Student Assistance Team (or the equivalent) to complete functional, behavioral, and/or psychological assessments. Based on the assessment results, the Team can then recommend, and facilitate the implementation of, teacher and classroom-based behavioral interventions, and student-centered social, emotional, and/or behavioral interventions.

In order to accomplish this, every district should have a comprehensive multi-tiered system of supports that includes the professional development needed by all teachers and administrators (e.g., in classroom management, engagement and de-escalation techniques, classroom-based behavioral interventions). This multi-tiered system also should include related services professionals (e.g., counselors, school psychologists, social workers) who have the behavioral assessment and strategic interventions skills (and time) to address students’ more intensive or complex psychoeducational needs.

But the reality is that most districts and schools do not have these systems or professionals in place.

_ _ _ _ _

Consistency

Consistency is a process. It would be great if we could “download” it into all students and staff. . . or put it in their annual flu shots. . . but that’s not going to happen.

Consistency needs to be “grown” experientially over time and, even then, it needs to be sustained in an ongoing way. It is grown through effective strategic planning with explicit implementation plans, good communication and collaboration, sound implementation and evaluation, and consensus-building coupled with constructive feedback and change.

It’s not easy. . . but it is necessary for school success. And it is especially important for students from minority backgrounds and SWDs.

In fact, studies have clearly demonstrated that some of the disproportionality in our schools occurs because some staff send minority students and SWDs to the Principal’s Office for the same (mild to moderate) behavioral offenses that they handle in the classroom with their white students. Said in “Behavioral Matrix” terms, these teachers are making Intensive III decisions when minority students and SWDs are demonstrating Intensive I (Annoying) or II (Classroom Disruptive) behaviors.

But relative to school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management, consistency must occur all four of the other interdependent components.

That is, in order to be successful, staff (and students) need to (a) demonstrate consistent prosocial relationships and interactions—resulting in consistently positive and productive school and classroom environments; (b) communicate consistent behavioral expectations, while consistently teaching and practicing them; (c) use consistent incentives and consequences, while holding student consistently accountable for their appropriate behavior; and then (d) apply all of these components consistently across all of the settings, circumstances, and peer groups in the school.

Moreover, consistency occurs when staff are consistent (a) with individual students, (b) across different students, (c) within their grade levels or instructional teams, (d) across time, (e) across settings, and (f) across situations and circumstances.

Critically, when staff are inconsistent, students feel that they are treated unfairly, they sometimes behave differently for different staff or in different settings, they can become manipulative—pitting one staff person against another, and they often emotionally react—some students getting angry with the inconsistency, and others simply withdrawing because they feel powerless to change it.

Said a different way: Inconsistency undercuts student accountability, and you don’t get the consistent social, emotional, or behavioral self-management that you want in class or across the school.

_ _ _ _ _

Implementation and Application Across All Settings and All Peer Groups

The last component of the school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management model focuses on the application of the previous four components to all of the settings, situations, circumstances, and peer/adult interactions in the school.

Relative to the first area, it is important to understand that the common areas of a school are more complex and dynamic than the classroom settings. Indeed, in the hallways, bathrooms, buses, cafeteria, and on the playground (or playing fields), there typically are more multi-aged or cross-grade students, more and varied social interactions, more space or fewer physical limitations, fewer staff and supervisors, and different social demands.

As such, the positive student social, emotional, and behavioral interactions that may occur more easily in the classroom often are more taxed in the common school areas.

Accordingly, minority students and SWDs need to be taught how to demonstrate their interpersonal, social problem solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional coping skills in each common school area. Moreover, the training needs to be tailored to the social demands and expectations of these settings.

Relative to the latter area, and as above, it is important to understand that the peer group is often a more dominant social and emotional “force” than the adults in a school. As such, the school’s approaches to student self-management must be consciously generalized and applied (relative to climate, relationships, expectations, skill instruction, motivation, and accountability) to help prevent peer-to-peer teasing, taunting, bullying, harassment, hazing, and physical aggression.

This is done by involving the different peer groups in a school in group “prevention and early response” training, and motivating them—across the entire school—to take the lead relative to prosocial interactions.

Truly, the more the peer group can be trained, motivated, and reinforced to do “the heavy prosocial lifting,” the more successful the staff and the school will be relative to positive school climate and consistently safe schools. And, the more successful students will be relative to social, emotional, and behavioral self-management.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

While they are important in reminding us that we have not successfully addressed disproportionality in our schools nationwide, and while they hold us continually accountable, we do not need to spend most of our time reading reports documenting this problem.

Instead, we need to do something functionally, systemically, and substantively about the problem.

This Blog has reviewed the science-to-practice components that have successfully addressed disproportionality in the thousands of schools we have worked in across the country.

With our partner schools, staff, and students, we have been successful because we have analyzed and addressed the underlying student- and staff-focused reasons for the problem—while implementing multi-tiered disciplinary and student service approaches along a prevention, strategic intervention, and intensive need continuum.

For more detailed research and practice support in this area, please consider my Corwin Press book:

School Discipline, Classroom Management, and Student Self-Management: A Positive Behavioral Support Implementation Guide.

CLICK HERE for more information.

If you are interested in this book, I am happy to provide the 100+ page Study Guide to this book FOR FREE.

[CLICK HERE and look down the page]

_ _ _ _ _

Meanwhile, I always look forward to your comments. . . whether on-line or via e-mail.

If I can help you in any of the multi-tiered areas discussed in this message, I am always happy to provide a free one-hour consultation conference call to help you clarify your needs and directions on behalf of your students.

As your school year winds down, please accept my best wishes for a safe end of the school year!!!

Best,