The Endrew F. Decision Re-Defines a “Free Appropriate Public Education" (FAPE) for Students with Disabilities (Part III of III)

Dear Colleagues,

Foreword

On March 22nd, the Supreme Court made history by expanding the depth and breadth of the “free appropriate public education” (FAPE) mandate in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) for all students with disabilities (SWD).

In their unanimous decision (Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District, 2017) the Supreme Court clarified and broadened the scope of SWD’s special education rights—building on their decision 35 years earlier in Board of Education of Hendrick Hudson Central School District, Westchester County v. Rowley (1982).

When taken together, the Rowley decision provides districts and schools FAPE-related guidance for SWDs who are educated in the regular education classroom. The Endrew F. decision provides FAPE-related guidance when SWDs need their educational programs largely outside of the regular education classroom—typically in a special education classroom or setting.

Given the importance of this decision for all educators, we have devoted three consecutive Blogs to both analyze and provide guidance—relative to students’ academic and social, emotional, and behavioral success—as we move ahead.

- In Part I : We used direct quotes from the Court’s ruling “tell Endrew’s story”—including why the Court took this significant case, how it differed from Rowley, and how it increases the “disability spectrum” relative to IDEA’s FAPE requirement.

- In Part II : We discussed a service and support blueprint for academically struggling students and SWDs to help schools to create academic multi-tiered, “FAPE-proof” system.

- Finally, in this Part III: We will discuss a service and support blueprint for SWDs (and others) who exhibit behavioral challenges to help schools create a multi-tiered social, emotional, behavioral “FAPE-proof” system.

Introduction

As noted above, on March 22nd, the Supreme Court made history by clarifying and expanding the depth and breadth of the “free appropriate public education” (FAPE) mandate in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) for all students with disabilities (SWD).

According to an April 4th Education Week article by Christina Samuels and Mark Walsh, some of the “Key Takeaways” from the Endrew F. decision are the following:

The court rejected a (FAPE) standard adopted by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit that an IEP is adequate as long as it provides a benefit that is “merely more than de minimis.” Roberts said a student offered an IEP under that standard “can hardly be said to have been offered an education at all.” He also noted that the IDEA requires an educational program (that is) “reasonably calculated to enable a child to make progress appropriate in light of the child’s circumstances,” Roberts said.

More specifically: For a child fully integrated into the regular classroom, an IEP typically should be “reasonably calculated to enable the child to achieve passing marks and advance from grade to grade.”

For a child not fully integrated into the regular classroom and for whom grade-level advancement is not a reasonable prospect, an IEP must be “appropriately ambitious,” providing the child the chance to “meet challenging objectives,” the court said.

The opinion rejected an argument put forth on behalf of Endrew F. that would require schools to provide students with disabilities the opportunity “to achieve academic success, attain self-sufficiency, and contribute to society that are substantially equal to the opportunities afforded children without disabilities.” Roberts said such a standard was at odds with the court’s analysis in Rowley.

Overall, the Supreme Court ruling recognized the individual nature of SWDs’ educational needs. That is, given the 13 disabilities areas covered within IDEA, different students will have different, and different intensities of, service, support, instructional, and intervention needs.

Comparing and Contrasting Amy Rowley vs. Endrew F.

The critical background points relative to the Rowley case are the following:

- Amy Rowley was a student whose disability involved having a hearing impairment.

- She was making “excellent progress in school”—“perform[ing] better than the average child in her (general education) class” and “advancing easily from grade to grade.” Her IEP provided her with “time each week with a special tutor and a speech therapist” and a “district propos(al) that Amy’s classroom teacher speak into a wireless transmitter and that Amy use an FM hearing aid designed to amplify her teacher’s words. . .”

- The 1982 Supreme Court only considered “the facts of (this) case before us,” and concluded that the individualized educational program described above “satisfied the FAPE requirement”—presumably, because Amy was making progress given the services provided.

- More specifically, the Court defined the provision of FAPE for students “receiving instruction in the regular classroom. . . (T)his would generally require an IEP ‘reasonably calculated to enable the child to achieve passing marks and advance from grade to grade.’”

- Beyond this case, the Supreme Court did not provide a “test” (or a series of decision rules) that could be used in future cases to determine the presence of FAPE.

In fact, as noted above, the Court acknowledged that IDEA requires states to “educate a wide spectrum of children with disabilities and that the benefits obtainable by children at one end of the spectrum will differ dramatically from those obtainable by children at the other end.”

The notable, functional differences between Amy Rowley and Endrew F. include the following:

- Endrew has a different disability than Amy—namely, autism, and the services provided in his IEP were not addressing his significant social, emotional, and behavioral needs such that he was not making progress in the regular classroom.

- Endrew’s IEP was not changing over time—from the District’s perspective because he was “failing to make meaningful progress toward his aims.” From the Parents’ perspective, Endrew’s lack of progress indicated that “only a thorough overhaul of the school district’s approach to Endrew’s behavioral problems could reverse th(is) trend.”

- Endrew’s attendance at a “private school that specializes in educating children with autism” resulted in behavioral improvements and “a degree of academic progress”—based on IEPs that provided him “a behavioral intervention plan that identified Endrew’s most problematic behaviors and set out particular strategies for addressing them.”

In summary: Endrew was different than Amy because (a) his disability was largely behaviorally-related (an area not addressed in the Rowley decision); (b) he was not making educational progress in the regular classroom (with the services and supports in his IEP); and (c) he needed more specialized and intensive interventions (in a substantially different special education placement and program).

With the Endrew F. ruling in hand, districts and schools need to review their research-based practices relative to how they are providing their multi-tiered continuum of services, supports, instruction, and intervention for different students with different disabilities and different intensities of need.

In order to do this, an evidence-based academic instruction and intervention blueprint was described in our last Blog message, HERE, once again, for this Blog]. Below, we will outline a complementary evidence-based social, emotional, and behavioral instruction and intervention blueprint.

Using both blueprints, schools and districts can evaluate their current multi-tiered continua, those elements that they need to maintain, the gaps that exist, and what steps are needed to close those gaps.

Critically, in order to provide an appropriate, differentiated FAPE to all SWDs, schools and districts need these two blueprints to help guide their IDEA-related prevention, assessment, and instruction/intervention processes.

A Multi-Tiered Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Model to Provide FAPE to ALL Students

Just as the “ultimate” goal of a multi-tiered academic system is helping every student to be an effective and independent learner (at their grade and developmental level). . .

. . . the “ultimate” goal of a multi-tiered behavioral system is helping every student to be an effective self-manager—socially, emotionally, and behaviorally—at their grade and developmental level.

Said a different way, the ultimate multi-tiered preschool through high school goal is to teach and motivate all students to progressively demonstrate the following:

- Accurate and insightful social, emotional, and behavioral awareness and understanding of themselves and others;

- Flexible and adaptive interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control and coping skills; and

- Effective and independent (over time) social, emotional, and behavioral skills and interactions across a variety of typical to challenging to unexpected and intense situations and circumstances.

These goals can only be accomplished by understanding the scientific, psychological foundation—once again—of social, emotional, and behavioral self-management.

But. . . what many educators may not fully understand is that this scientific, psychological foundation is the same foundation needed to prevent and address:

- Virtually all of the social problems exhibited by students (for example, teasing, taunting, bullying, and physical aggression;

- Virtually all of the emotional problems exhibited by students (for example, their reactions to different life crises or traumas); and/or

- Virtually all of the behavioral problems exhibited by students (e.g., their disobedience, disruptions, disrespect, and defiance).

Moreover, in the context of a multi-tiered system, these goals can only be accomplished by organizing the social, emotional, and behavioral instruction needed to teach and motivate all students—and the additional strategies, services, and supports needed by challenging students—along a prevention, strategic intervention, and intensive need/crisis management continuum.

Thus, for the students demonstrating mild to extreme socially, emotionally, or behaviorally inappropriate behaviors, reactions, or interactions, the multi-tiered approach must include (a) strategic or intensive strategies, services, supports, and/or interventions that decrease or eliminate the challenges; with (b) concurrent or complementary approaches that replace the challenges with expected, appropriate, prosocial, and self-managing behaviors.

Below, we will first discuss the psychological science underlying students’ social, emotional, and behavioral self-management.

Then, we will discuss the prevention, strategic intervention, and intensive need/crisis management continuum.

The Scientific Components of Self-Management Introduced

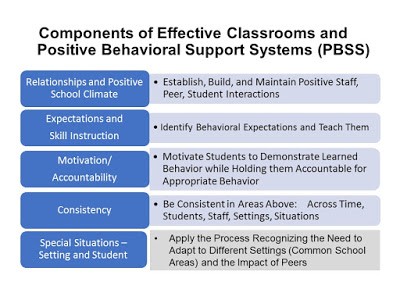

There are five interdependent components (see figure below) that “anchor” the underlying science of social, emotional, and behavioral self-management:

- Positive Relationships and School/Classroom Climate

- Positive Behavioral Expectations and Skills Instruction

- Student Motivation and Accountability

- Consistency

- Implementation and Application Across All Settings and All Peer Groups

Unfortunately, as noted above, some educators (largely because they are trained in education, not psychology) may not know or fully understand these components—and how they interact.

And so, in their quest for solutions to address a wide range of social, emotional, and/or behavioral issues and problems, these same educators too often introduce “programs” or “frameworks” into their schools and classrooms that are endorsed, advocated, or marketed by others (including the U.S. and some state Departments of Education, some “trusted” publishers, and some notable “thought leaders”) that . . .

Do not focus on social, emotional, and behavioral awareness, skills, competence, and self-management as their primary outcomes;

Do not have the necessary scientific, psychological foundations, or integrate all five of the interdependent components;

Do not correctly translate the science into evidence-based practices;

Have not been field-tested in a wide variety of representative settings, situations, and circumstances; and

Have not been independently evaluated using objective multi-assessment, multi-setting, multi-trait, multi-respondent tools and approaches.

At other times, these educators introduce and implement “niche” programs in an attempt to address one significant problem—with the hope that the program will (magically) generalize to other problems.

Some of these niche programs are being advocated or marketed across the country in such areas as:

- Cultural Competence

- Character Education

- Poverty Awareness

- Social-Emotional Learning

- Trauma Sensitivity

- Mindfulness

- Restorative Justice

- Teasing and Bullying Programs

And this is not to say that these areas or concerns are not legitimate.

This IS to say that all of these strategies, programs, or frameworks will not be successful unless (a) they integrate the five components above; and (b) have been (also as above) effectively, objectively, and successfully designed, field-tested, evaluated, and scaled-up.

The Scientific Components of Self-Management Described

In the broader context of school discipline and classroom management, the five interdependent components that comprise the scientific, psychological foundation to students’ social, emotional, and behavioral self-management are briefly described below.

These components have been field-tested and validated in thousands of schools across the country over a 35+ year period. . . but most important, they have been validated as part of Project ACHIEVE’s Positive Behavioral Support System (PBSS) and multi-tiered system of services and supports (www.projectachieve.net).

This is significant because Project ACHIEVE was designated an evidence-based model in these areas by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) in 2000; and it was listed on the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (NREPP) because of this designation.

As an “advanced organizer” to the descriptions, below is a brief, ten-minute YouTube presentation that overviews these components and how they positively impacted schools across Arkansas as part of a multi-year, state-wide scale-up federal grant.

Positive Relationships and School/Classroom Climate

Effective schools work consciously, planfully, and on an on-going basis to develop, reinforce, and sustain positive and productive relationships so that their cross-school and in-classroom climates mirror these relationships.

Critically, however, these relationships include the following: Students to Students, Students to Staff, Staff to Staff, Students to Parents, and Staff to Parents.

And functionally, they involve training and reinforcement. For example, students need to learn the social and interactional skills that build positive relationships with others, and the peer group must “buy into” the process.

Similarly, teachers need to recognize the importance of committing to effective communication, collaboration, and collegial consultation. But, they also need to have the skills to accomplish these. . . in good times and bad.

All of this generalizes to self-management. When students have good social, emotional, and behavioral self-management skills, they rarely demonstrate them in negative, aversive, or toxic environments.

When they don’t have these skills, the absence of positive relationships and school/classroom climates often impede the instruction, their learning, or their motivation to learn.

Positive Behavioral Expectations and Skills Instruction

Students—from preschool through high school—need to know the explicit social, emotional, and behavioral expectations in the classrooms and across the common areas of the school. These expectations need to be communicated in a prosocial way as “what they need to do,” rather than in a negative, deficit-focused way as “what they do not need to do.”

Indeed, teachers and administrators have more success teaching students to (a) walk down the hallway, rather than do not run; (b) raise your hand and wait to be called on, rather than don’t blurt out answers; (c) accept a consequence, rather than don’t roll your eyes and give me attitude.

In addition, these expectations need to be behaviorally specific—that is, we need to describe exactly what we want the students to do (e.g., in the hallways, bathrooms, cafeteria, and on the bus).

Moreover, it is not instructionally helpful to talk in constructs—telling students that they need to be “Respectful, Responsible, Polite, Safe, and Trustworthy.” This is because each of these constructs involve a wide range of behaviors. At the elementary school level, students really do not functionally or behaviorally understand these higher-ordered thinking constructs. At the secondary level, students may interpret these constructs (and their many inherent behaviors) differently than staff.

And it is the behaviors that we need to teach . . . so that students can fully demonstrate the global constructs that we want.

In the final analysis, however: You can’t teach a behavioral construct. You need to teach the behaviors that are represented within each construct that you want your students to demonstrate.

Thus, beyond specifying the social, emotional, and behavioral expectations in a school or classroom, these social, emotional, and behavioral skills must be taught as part of classroom management.

In fact, these skills are taught the same way that we teach a football team their offensive or defensive schemes and plays, an orchestra its music and movements, a drama club and actors a play’s scenes and lines, or a student how to break-down and learn a specific academic task.

And, the teaching methodology that needs to be used involved social learning theory. Explicitly, we need to teach the skills and their steps, to demonstrate them, to give students opportunities to practice them and receive feedback, and then to help students to apply their new skills to “real-world” situations.

Relative to self-management and this component, we need to communicate our social, emotional, and behavioral expectations to students, and then teach them to perform them—in different settings, with different people, in different contexts, and under different conditions of emotionality. Functionally, this means that our schools need to consciously and explicitly set aside time for social skills instruction, and then embed the application of this instruction into their classrooms and group activities, and (for example) cooperative and project-based instruction.

Student Motivation and Accountability

For the skill instruction described above to “work,” students need to be held accountable for demonstrating positive and effective social, emotional, and behavioral skills. But to accomplish this, students need to be motivated (eventually, self-motivated) to perform these skills.

Motivation is based on two component parts: Incentives and Consequences. But critically, these incentives and consequences must be meaningful and powerful to the students (not just to the adults in a school).

Too often, schools create “motivational programs” for students that involve incentives and consequences that the students couldn’t care less about. Thus, it looks good “on paper,” but it holds no weight in actuality—from the students’ perspectives.

At other times, schools forget that they need to recognize, engage, and activate the peer group in a motivational program. This is because, at times, the peer group actually is undermining a positive behavioral program by negatively reinforcing specific students (on the playground, after school, on social media). These students then “behave” appropriately only when they are interacting one-on-one with adults (i.e., in the absence of the “negative” peer group), and they behave inappropriately with adults in the presence of the peer group—to avoid later (on the playground, after school, etc.) peer disapproval, rejection, or aggression.

On a functional level, both incentives and consequences result in positive and prosocial behavior. The incentives motivate students toward the expected behaviors, and the consequences motivate students away from the inappropriate behaviors (and, again, toward the expected ones).

But critically, educators need to understand that you can only create motivating conditions. That is, we can’t force students to meet the social, emotional, and behavioral expectations. Indeed, when we force students to do anything, we are managing their behavior, not facilitating self-management. And while we have to do some adult management to get to student self-management. . . if we only manage students’ behavior, then they will not (know how to) self-manage when the adults are not present.

Ultimately, relative to this component, the goal is self-motivation and self-accountability. When this occurs, we have a high probability of comprehensive student self-management.

Consistency

Consistency is a process. It would be great if we could “download” it into all students and staff. . . or put it in their annual flu shots. . . but that’s not going to happen.

Consistency needs to be “grown” experientially over time and, even then, it needs to be sustained in an ongoing way. It is grown through effective strategic planning with explicit implementation plans, good communication and collaboration, sound implementation and evaluation, and consensus-building coupled with constructive feedback and change.

It’s not easy. . . but it is necessary for school success.

But relative to school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management, consistency must occur all four of the other interdependent components.

That is, in order to be successful, staff (and students) need to (a) demonstrate consistent prosocial relationships and interactions—resulting in consistently positive and productive school and classroom environments; (b) communicate consistent behavioral expectations, while consistently teaching and practicing them; (c) use consistent incentives and consequences, while holding student consistently accountable for their appropriate behavior; and then (d) apply all of these components consistently across all of the settings, circumstances, and peer groups in the school.

Moreover, consistency occurs when staff are consistent (a) with individual students, (b) across different students, (c) within their grade levels or instructional teams, (d) across time, (e) across settings, and (f) across situations and circumstances.

Critically, when staff are inconsistent, students feel that they are treated unfairly, they sometimes behave differently for different staff or in different settings, they can become manipulative—pitting one staff person against another, and they often emotionally react—some students getting angry with the inconsistency, and others simply withdrawing because they feel powerless to change it.

Said a different way: Inconsistency undercuts student accountability, and you don’t get the consistent social, emotional, or behavioral self-management that you want in class or across the school.

A football coach, orchestra conductor, drama director, or classroom teacher (academically) would never teach, practice, or reinforce their “skills” inconsistently. Neither should those responsible for the social, emotional, and behavioral program (which necessarily involves everyone) in a school.

Implementation and Application Across All Settings and All Peer Groups

The last component of the school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management model focuses on the application of the previous four components to all of the settings, situations, circumstances, and peer/adult interactions in the school.

Relative to the first area, it is important to understand that the common areas of a school are more complex and dynamic than the classroom settings. Indeed, in the hallways, bathrooms, buses, cafeteria, and on the playground (or playing fields), there typically are more multi-aged or cross-grade students, more and varied social interactions, more space or fewer physical limitations, fewer staff and supervisors, and different social demands.

As such, the positive student social, emotional, and behavioral interactions that may occur more easily in the classroom often are more taxed in the common school areas.

Accordingly, students need to be taught how to demonstrate their interpersonal, social problem solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional coping skills in each common school area. Moreover, the training needs to be tailored to the social demands and expectations of these settings.

Relative to the latter area, and as above, it is important to understand that the peer group is often a more dominant social and emotional “force” than the adults in a school. As such, the school’s approaches to student self-management must be consciously generalized and applied (relative to climate, relationships, expectations, skill instruction, motivation, and accountability) to help prevent peer-to-peer teasing, taunting, bullying, harassment, hazing, and physical aggression.

This is done by involving the different peer groups in a school in group “prevention and early response” training, and motivating them—across the entire school—to take the lead relative to prosocial interactions.

Truly, the more the peer group can be trained, motivated, and reinforced to do “the heavy prosocial lifting,” the more successful the staff and the school will be relative to positive school climate and consistently safe schools. And, the more successful students will be relative to social, emotional, and behavioral self-management.

The Multi-Tiered Prevention, Strategic Intervention, and Intensive Need/Crisis Management Continuum

As discussed in the introductory sections of this Blog, all students will not learn, master, or be able to apply their social, emotional, and behavioral self-management skills unless the five scientific, psychological components are implemented across a multi-tiered prevention, strategic intervention, and intensive need/crisis management continuum.

For the students demonstrating mild to extreme socially, emotionally, or behaviorally inappropriate behaviors, reactions, or interactions, the multi-tiered approach must include (a) strategic or intensive strategies, services, supports, and/or interventions that decrease or eliminate the challenges; with (b) concurrent or complementary approaches that replace the challenges with expected, appropriate, prosocial, and self-managing behaviors.

In past Blogs, I have discussed how the “new” Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) encourages states, districts, and schools to re-think their multi-tiered approaches so that they best address the needs of their respective students.

I have also cautioned—if not criticized—the U.S. Department of Education’s (and, hence, many state departments of education) untested, flawed, and unsuccessful MTSS and PBIS approaches (based on federal reports investigating many states and settings across the country).

Critically, embedded in my criticism is the fact that there are no federal education laws that require the U.S. Department of Education’s MTSS or PBIS frameworks, and that many districts and schools have been misled regarding this fact.

As proof: when these terms appear in federal law (largely ESEA and IDEA), they appear generically in LOWER CASE terms, and WITHOUT ACRONYMS.

And yet, the U.S. Department of Education (primarily through its various federally-funded National Technical Assistance Centers) have either misquoted the law, or allowed educators to confuse the lower case terms in federal law with their UPPER CASE use of the terms—often in the names of the TA Centers themselves.

For those interested in these past discussions, you can read the following past BLOGS:

Your State’s Guide to RtI Just Doesn’t Make Sense (February, 2015)

A Brief Description of the Prevention, Strategic Intervention, and Intensive Need/Crisis Management Tiers

Right from the beginning, it is important to emphasize that the Tiers should not be defined or organized by: percentages of students, places where services are delivered, who is responsible to deliver specific services, or when certain student assessments should be conducted.

In fact, it is easiest to define the Tiers as existing along a continuum reflecting the intensity of services, supports, strategies, and interventions that specific students need in a specific goal-oriented academic and/or social, emotional, behavioral area.

Thus, there are not “Tier II” students. Instead, there are students who need “Tier II” services, supports, strategies, or interventions—for example, to help them with emotional self-control, or academic motivation, or to increase their conflict prevention and resolution skills.

Significantly, the designation of a service, support, strategy, or intervention into a particular Tier is somewhat relative across schools and districts. For example, the same intervention may be considered a Tier I, II, or III support based on such factors as the level of staff training and expertise, the presence of on-site versus off-site intervention staff, or the presence or absence of intervention technology.

Thus, what is a “Tier II” intervention in a well-resourced school or district might be a “Tier III” intervention in a lesser-resourced school or district.

All of this is reinforced by ESEA—which defines a "multi-tier system of supports" (NOTE the lower case language) as:

"a comprehensive continuum of evidence-based, systemic practices to support a rapid response to students' needs, with regular observation to facilitate data-based instructional decision-making."

NOTE that ESEA does not require any number of Tiers, and the practices are in response to a specific student’s needs.

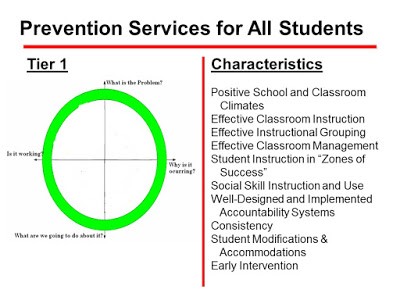

In general, the Prevention Tier of a multi-tiered continuum involves academic and social, emotional, and behavioral instruction and interventions that occur in the general education classroom, involving the general education curriculum, largely directed by the general education teachers.

While some students may be receiving Tier II or Tier III services or supports to help them succeed in the general education curriculum, some of the “typical” components within Tier I are shown in the figure below.

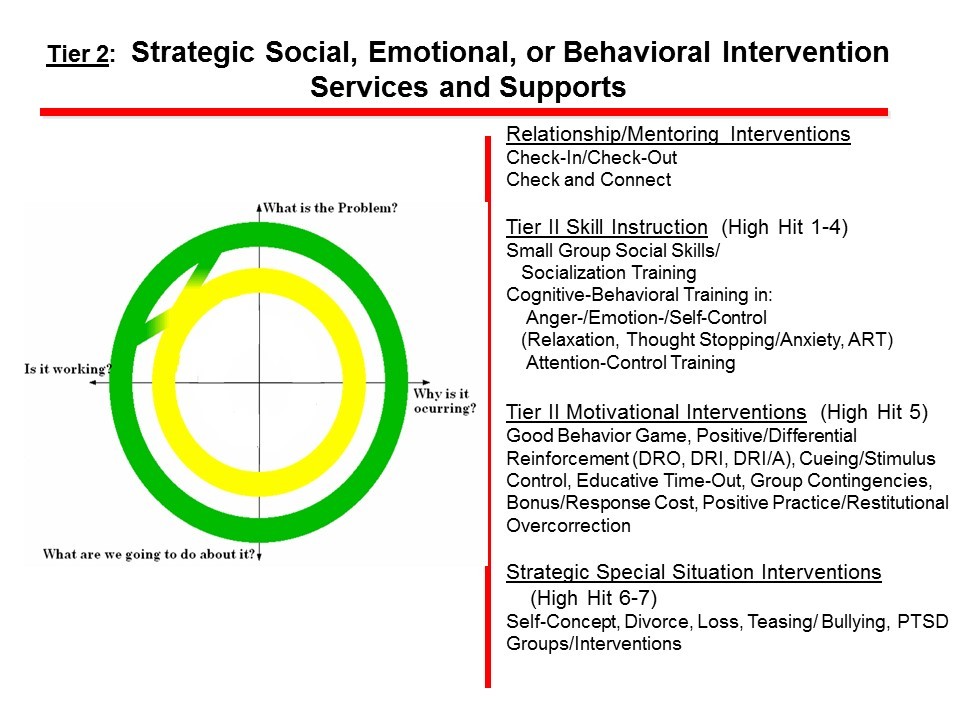

In general, the Strategic Intervention Tier of a multi-tiered continuum is needed when students do not respond to the preventative approaches or strategies being implemented across the five scientific components discussed earlier in this Blog.

At this Strategic level, data-based functional social, emotional, or behavioral assessments need to be conducted to determine the underlying reasons for a student’s significant non-responding, negatively responding, or inappropriately responding behavior. The results of these assessments then are linked to strategic social, emotional, or behavioral instruction or intervention approaches. These approaches are implemented to the greatest degree possible in the general education classroom by the general education teacher with consultative support from related service or other intervention specialists.

As one part of the functional assessment, Project ACHIEVE differentiates among the “Seven High-Hit Reasons” for students’ significantly challenging behavior. These High-Hit Reasons include the following:

Reason #1: The Student has never learned, mastered, or can/is not applying the expected behavior (Skill Deficit)

Reason #2: The Student is learning social, emotional, and behavioral skills, but at a slower rate than his/her peers (Speed of Acquisition)

Reason #3: The Student can demonstrate the appropriate behavior in one setting, but not all settings (Transfer of Training/Generalization)

Reason #4: The Student can demonstrate the appropriate behavior when things are “calm,” but not when “agitated” (Conditions of Emotionality)

Reason #5: The Student can demonstrate the behavior, but is choosing not to (Motivation/Performance Deficit)

Reason #6: There has been inconsistent conditions, instruction, motivation, or accountability that has resulted in inconsistent student behavior (Inconsistency)

Reason #7: There is some “Special Situation” (e.g., a traumatic event or situation) in a school setting, involving the student’s peer group, or in the home or community that has/is significantly affecting the student’s behavior (Special Situation)

This functional behavioral assessment approach is far more comprehensive than the FBA approaches used in most districts. In fact, the “traditional” FBA approach has not changed in over 25 years—despite new research that has extended the possible reasons underlying student (mis)behavior.

Regardless, there are an extensive number of possible social, emotional, and behavioral interventions that are matched to the Seven High-Hit Reasons underlying many students’ behavior. Some of these are identified in the figure below.

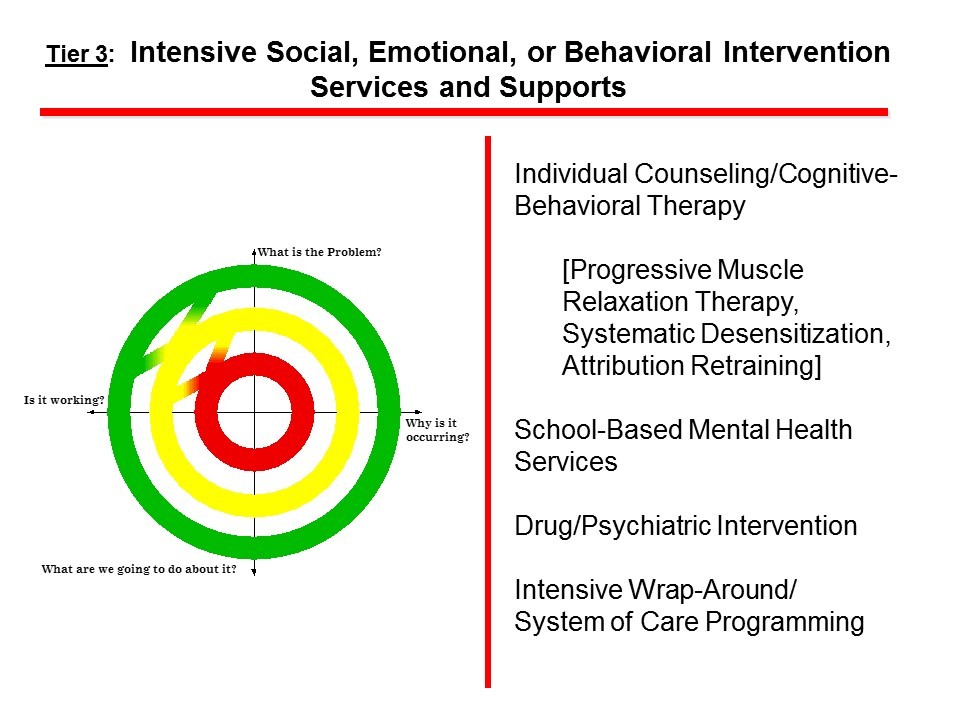

Finally, the Intensive Need/Crisis Management Tier of a multi-tiered continuum is needed when students are chronically non-responsive to effectively-implemented interventions, or when their social, emotional, or behavioral challenges are significant, extreme, or at a crisis level. CLICK HERE for more information.

Finally, the Intensive Need/Crisis Management Tier of a multi-tiered continuum is needed when students are chronically non-responsive to effectively-implemented interventions, or when their social, emotional, or behavioral challenges are significant, extreme, or at a crisis level.

Critically, students do not need to experience Tier I and/or Tier II services, supports, strategies, or interventions in order to “qualify” for Tier III services. Indeed. . . . if you need to go to the emergency room, you go to the emergency room. You do not have to “try” specific medical procedures or interventions for a specific amount of time—and have these interventions “fail”—in order to have the emergency room door “swing open.”

Thus, if a student needs what a school or district considers a Tier III service, the student gets that service.

Because the multi-tiered system of supports is more about the intensity of services, supports, strategies, and interventions than anything else, many Tier III interventions are actually Tier II interventions that are simply implemented with more intensity (e.g., more frequency, more individualized, more consultative complexity or expertise, etc.).

However, as represented in the figure below, some more clinically-oriented psychological interventions can occur at Tier III—interventions that are typically only provided by clinically-trained school psychologists, clinical psychologists, or other licensed mental health therapists.

Critical Points

While there is a sequential nature to the multi-tiered social, emotional, and behavioral/Positive Behavioral Support System (PBSS) continuum, it is a strategic and fluid—not a lock-step—blueprint. That is, the supports and services are utilized based on students’ needs, as well as the intensity of those needs.

Critically, many students with complex needs will receive different supports or services on the PBSS continuum simultaneously—and, they also might be receiving supports or services on the academic PASS continuum (see Part II of this Blog series).

Thus, consistent with the Rowley and Endrew F. decisions, all PBSS services, supports, strategies, and programs are strategically delivered to individual students with individually assessed needs. And while it is most advantageous to have the general education teacher deliver needed supports and services in the general education classroom (i.e., the least restrictive environment), other intervention options might include pull-in services (e.g., by special education teachers, counselors, school psychologists, school social worker coming into a general education classroom), short-term pull-out services (e.g., by these same related services personnel), or more intensive pull-out services (e.g., to include school-based or school-linked psychologists or other therapists).

With a conscious eye to FAPE—relative to Students with Disabilities (SWD), these staff and setting decisions are based on the intensity of students’ social, emotional, and behavioral needs; their response to previous intervention services and supports; the seriousness of the problem at-hand; and the level and intensity of intervention expertise needed.

Summary

Ultimately, the goal of the multi-tiered PBSS continuum is to provide students with early, intensive, and successful services and supports that are identified through a functional assessment/problem-solving process, and implemented with integrity and needed intensity. For the more strategic and intensive strategies and interventions in the continuum, the results of the functional assessments are linked directly to the interventions. This selection and implementation process helps to ensure FAPE.

Returning back to Endrew F.: As an expansion of Rowley, the Endrew F. decision helps us understand some basic principles relative to the delivery of FAPE to SWDs:

- The Supreme Court stated, “The goals may differ, but every child should have the chance to meet challenging objectives. Of course, this describes a general standard, not a formula. But whatever else can be said about it, this standard is markedly more demanding than the “merely more than de minimis” test applied by the Tenth Circuit.”

- FAPE must be determined in the context of how a student’s disability impacts the services and supports needed in an IEP (“in light of a child’s circumstances”).

- WDs are not guaranteed to make educational progress.

- Having considered only two cases, involving two different disabilities (of the 13 specified in IDEA), and two different intensity levels of individualized educational need, the Court does not believe it appropriate (or even possible) to identify set decision rules relative to a district’s provision of FAPE.

- The Court noted its “deference” to the expertise and judgement of the professionals in a school district—albeit in a partnership with the Parents—when writing an IEP, and it “vests these officials with responsibility for decisions of critical importance to the life of a disabled child.”

- Finally, the Court stated that IDEA’s provision of FAPE did not include “an education that aims to provide a child with a disability opportunities to achieve academic success, attain self-sufficiency, and contribute to society that are substantially equal to the opportunities afforded children without disabilities.”

Conclusion

As you “journey” toward the end of this school year, I hope this overview of the multi-tiered social, emotional, and behavioral (PBSS) continuum, and its connection to the Supreme Court’s Endrew F. FAPE decision, has provided a blueprint to help you to evaluate, validate, and/or change your current district or school approaches to SWDs (and others) exhibiting challenges in these areas.

I also hope that the first two Blogs also have provided an understanding of the Supreme Court decision itself (Part I), and how the decision relates to students with academic intervention needs (Part II).

Relative to the social, emotional, and behavioral area, know that I have written much more extensively in my recent Corwin Press book:

If you are interested in this book, I am happy to provide the 100+ page Study Guide to this book FOR FREE.

All you have to do is to e-mail me

( knoffprojectachieve@earthlink.net ), and request the Guide.

Meanwhile, I always look forward to your comments... whether on-line or via e-mail.

If I can help you in any area of the multi-tiered school and schooling process, I am always happy to provide a free one-hour consultation conference call to help you clarify your needs and directions on behalf of your students.

I am also happy to come to your school or district to guide a “more personalized” and individually-tailored implementation. I am currently working with 15 or more school districts—all over the country and abroad.

Best,

Howie