Classroom Management and Students’ (Virtual) Academic Engagement and Learning: Don’t Depend on Teacher Training Programs

Districts Need to Reconceptualize their School Discipline Approaches—For Equity, Excellence, and Effectiveness

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

This past week, the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) released its 2020 Teacher Prep Review: Clinical Practice & Classroom Management, an analysis of how over a thousand elementary teacher preparation programs train, supervise, and certify their graduates in five research-based strategies that are essential to classroom management. The NCTQ Report compared its current results with its past 2013 and 2016 results and reports.

The five research-based classroom management strategies studied were:

- Establishing rules and routines that set expectations for behavior;

- Maximizing learning time;

- Reinforcing positive behavior;

- Redirecting off-task behavior without interrupting instruction; and

- Addressing serious misbehavior with consistent, respectful, and appropriate consequences.

Critically, these are the bare essential strategies needed for effective classroom management.

While their presence increases the probability that a teacher can establish the positive classroom climate and control needed to maximize students’ academic engagement and learning, this still is not ensured. Indeed, classroom management is more than just these five strategies. Moreover, in the absence of teachers’ effective curricular preparation and pedagogically-sound instruction, the achievement needed by all students simply will not occur.

Added to this, given the current pandemic, is classroom management and effective instruction in both on-site/physically present and off-site/virtual settings.

But let’s stay within the confines of the NCTQ Report right now.

And, for the record, know that the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) is a nonpartisan, not-for-profit research and policy organization committed to modernizing the teaching profession. It accepts no funding from the federal government, and it routinely conducts research to assist states, districts, and teacher preparation programs with teacher quality issues.

[CLICK HERE for the NCTQ Report]

_ _ _ _ _

Relative to the NCTQ’s 2020 Clinical Practice & Classroom Management Report—which evaluated 979 traditional teacher preparation programs (typically housed in universities) and 40 alternative preparation programs, its most important outcomes included:

- Just 14% of traditional teacher-preparation programs, and a third of the non-traditional programs, require candidates to demonstrate their skill in the five research-based classroom management strategies noted above.

- Only 35% of these programs require their graduates to demonstrate their skill in four of the five strategies.

- The results immediately above actually reflect a significant increase, since 2013, in the number of programs focusing on these strategies.

- But surely, this “increase” points especially to how slowly teacher training programs are modifying and upgrading this essential classroom management training and student supervision.

- Finally, 13% of the traditional teacher preparation programs required their candidates to demonstrate just one or none of the five strategies, and fewer than a third of the programs taught their graduates how to reinforce good classroom behavior with praise.

Relative to mentoring prospective teachers, the NCTQ studied how 1,180 traditional and 59 alternative teacher preparation programs, respectively, implemented their student teaching requirements.

Utilizing objective, evidence-based criteria, the Report concluded:

- Only 65% of the traditional teacher preparation programs earned a "C" grade on their clinical practice.

- While nearly all of the programs required at least 10 weeks of student teaching, and 71% of the programs provided an appropriate number of supervisor-student teacher classroom observations, most of the programs had no involvement in selecting the mentor teacher. This leaves the expert quality of the supervision in question.

- Indeed, only 4% of the teacher preparation programs validated the instructional and/or supervisory skills of the teacher assigned to their teacher-candidate.

Thus, the preparation programs typically accepted the supervisor chosen by the district—which, past studies suggest—is often whoever volunteers regardless (once again) of their own instructional and/or supervisory skills.

_ _ _ _ _

The most conservative conclusions from this study are:

- Newly graduating and certified or licensed elementary classroom teachers are clinically unprepared in basic classroom management, climate enhancement, and student engagement skills.

- Based on this and studies dating back to the 1980s, virtually all of the elementary classroom teachers in our classrooms today have never received the formal pre-service training or supervision needed for immediate classroom management success.

- Districts cannot depend on teacher preparation programs to change.

Indeed, “past (ineffective) training and supervision behavior predicts future (ineffective) behavior.”

Thus, Districts must provide the hands-on professional development, training, and supervision needed to ensure that all of their teachers learn, master, and consistently demonstrate the classroom management skills needed for student and teacher success.

And yet, we also know that the needed professional development, training, and supervision is not happening in most districts, and that many students are negatively impacted because of this.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

The Inequity Implications of Poor Classroom Management

There is no need to rehash the extensive body of research-to-practice studies that address what occurs when teachers have ineffective classroom management skills—especially due to inadequate pre-service and post-certification training and supervision.

Some of the most notable outcomes include:

- Classroom climates that range from neutral to negative to toxic

- Poor student-teacher and student-student relationships and interactions

- Student responses that range from disengagement to class/school skipping to chronic absenteeism

- Teacher responses that range from disengagement to teacher absences to teacher resignations

- Less effective to impaired student learning, mastery, and proficiency

- Increases in inappropriate student classroom behavior that often results in disproportionate office discipline referrals and suspensions for students of color and students with disabilities

All of these outcomes are notable for all students. And while there are many teachers across the country who have excellent classroom management and instructional skills, many of them “learned their craft” over a period of years.

But—not to be critical—how many students did not receive the excellence that these teachers now provide during their “learning years?”

And, how many teachers still have not attained this level of excellence. . . and are negatively impacting their students, colleagues, and schools in the ways delineated above?

_ _ _ _ _

Another Recent Report on Inequity

As above, the issue of inequity is clearly “on the table” when we discuss teachers’ (lack of) classroom management skills.

This is because it is well-established that students of color and with disabilities often receive more extreme responses (i.e., being sent to the Principal’s Office, and being suspended) for the same (often low-level) classroom behavior issues as their white peers (who receive more relationship-related responses).

While classroom management training and application necessarily intersect with teachers’ training and understanding of how to interact with students of different cultures, races, and disabilities, the disproportionate data are irrefutable.

And at this time when schools and districts need to address the racial inequities of the past (along with inequities related to students’ socio-economic and disability status), the area of school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management should be at the top of this list.

This has, once again, been reinforced by a new report from the UCLA Civil Rights Project (October 11, 2020), Lost Opportunities: How Disparate School Discipline Continues to Drive Difference in the Opportunity to Learn.

This Report’s Executive Summary states (with edits):

During the 2015–16 school year, according to national estimates released by the U.S. Department of Education in May 2020, there were 11,392,474 days of instruction lost due to out-of-school suspension. That is the equivalent of 62,596 years of instruction lost. The counts of days of lost instruction were collected and reported for nearly every school and district by the U.S. Department of Education.

Considering the hardships all students are experiencing during the pandemic, including some degree of suspended education, this shared experience of having no access to the classroom should raise awareness of how missing school diminishes the opportunity to learn. The stark disparities in lost instruction due to suspension described in this report also raise the question of how we can close the achievement gap if we do not close the discipline gap.

The racially disparate harm done by the loss of valuable in-person instruction time when schools closed in March 2020 is even deeper for those students who also lost access to mental health services and other important student support services. The same losses, plus the stigma of punishment, is what suspended students experience when removed from school for breaking a rule, no matter how minor their misconduct.

According to experts, the coronavirus is likely more harmful to children from low-income families, those with disabilities, and children of color. Coming on the heels of a massive loss of instructional time, and of mental health and special education supports and services, the data describing the high rates of lost instruction and the inequitable disparate impact of suspensions in these times of extreme stress should compel educators across the nation to do more, once students are allowed to return, to reduce disciplinary exclusion from school.

The analysis presented here helps to convey how high and disparate levels of exclusionary discipline in terms of days of lost instruction time contribute to large inequities in educational opportunity.

The key findings of most significance in this report are:

• In many districts, secondary students lost over a year of instruction (per 100 enrolled students). The disaggregated district data showing the rates of lost instruction are often shocking to the conscience.

• Rates of lost instruction reveal that due to out-of-school suspensions, students at the secondary level lose instruction at rates that are five times higher than those at the elementary level. The distinction between elementary and secondary rates. . . demonstrates how the traditional form of reporting the data for all grades, k–12, obscures the highest rates and largest disparities.

• National trend lines in rates of student suspension for 2015–16 show reduced reliance by schools on both in- and out-of-school suspensions, and a slight narrowing of the racial discipline gap, yet there are many districts in which student suspension rates are much higher than the national average, and many also show rising rates and widening racial disparities.

• Students attending alternative schools experience extraordinarily high and profoundly disparate rates of lost instruction.

• There is a widespread failure by districts to report data on school policing despite the requirements of federal law. Specifically, over 60% of the largest school districts (including New York City and Los Angeles) reported zero school-related arrests. The prevalence of zeros suggests that much of the school-policing data from 2015–16 required by the federal Office for Civil Rights (OCR) were incomplete or missing.

_ _ _ _ _

The Report concluded:

“In all districts, including those that show a decline in the student suspension rate, policymakers, advocates, and educators must pay closer attention to the rates of lost instruction for students at the secondary level, the use of suspension in alternative schools, and the use of referrals to law enforcement as a response to student misconduct in school. The data analyzed in this report, all of which was collected by the U.S. Department of Education, reveal deeply disturbing disparities and demonstrate how the frequent use of suspension contributes to inequities in the opportunity to learn.”

We conclude:

There are many possible inter-related factors that contribute to the outcomes described in the Report above. They include: (a) inequitable or insufficient school funding, (b) poorly designed or ineffectively implemented district and school discipline policies and practices, (c) poor or underfunded multi-tiered intervention systems for students with challenging behavior, or (d) institutional or implicit bias or prejudice.

But, to return to today’s theme, we need to disaggregate these factors, and take action in areas that produce tangible student and staff results, while moderating the negative impact of the factors above.

Critically, improving and enhancing teachers’ classroom management skills is one essential area of action.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

The Classroom Management Skills in Effective Classrooms

As noted earlier, effective classroom management consists of more than the five strategies investigated in the NCTQ Report described above. So, let’s look at some of the critical, evidence-based teacher skills and interactions that better define this area.

To guide and maximize this discussion, we will use Charlotte Danielson’s Framework for Teaching—highlighting the domains and components most relevant to effective classroom management. This research-based blueprint was chosen because it is still the teacher evaluation foundation for many states and districts across the country.

But before taking this “deeper dive,” it must be emphasized that the research-based classroom management skills below are presented not for the purpose of teacher evaluation. They are detailed to encourage districts and schools to include them as primary professional development, coaching, and mentoring targets for new (and existing) teachers.

_ _ _ _ _

Danielson’s Classroom Management-Related Domains

While effective and exciting curriculum and instruction are integral to classroom management given their effects on student motivation and engagement, seven Danielson components within three domains most directly relate to classroom management.

They are:

- Domain 1. Planning and Preparation

1b. Demonstrating Knowledge of Students

- Domain 2. The Classroom Environment

2a. Creating a Climate of Respect and Rapport

2b. Creating a Culture of Learning

2c. Managing Classroom Procedures

2d. Managing Student Behavior

- Domain 3: Instruction

3a. Communication with Students

3c. Engaging Students in Learning

_ _ _ _ _

These components are briefly described below (as edited from the Framework for Teaching).

Domain 1b. Demonstrating Knowledge of Students. Teachers don’t teach content in the abstract; they teach it to students. In order to ensure student learning, therefore, teachers must know not only their content and its related pedagogy but also the students to whom they wish to teach that content.

The elements of this component are: (a) Knowledge of child and adolescent development; (b) Knowledge of the learning process; (c) Knowledge of students’ skills, knowledge, and language proficiency; (d) Knowledge of students’ interests and cultural heritage; and (e) Knowledge of students’ special needs.

Indicators include: (a) Formal and informal information about students gathered by the teacher for use in planning instruction; (b) Student interests and needs learned by the teacher for use in planning; (c) Teacher participation in community cultural events; (d) Teacher-designed opportunities for families to share their heritages; and (e) Databases of students with special needs.

_ _ _ _ _

Domain 2a. Creating a Climate of Respect and Rapport. An essential skill of teaching is that of managing relationships with students and ensuring that relationships among students are positive and supportive. Teachers create an environment of respect and rapport in their classrooms by the ways they interact with students and by the interactions they encourage and cultivate among students. An important aspect of respect and rapport relates to how the teacher responds to students and how students are permitted to treat one another. In a respectful environment, all students feel valued, safe, and comfortable taking intellectual risks. They do not fear put-downs or ridicule from either the teacher or other students.

The elements of this component are: How teachers, through their interactions, (a) convey that they are interested in and care about their students; and (b) guide and reinforce students’ respectful interactions with one another through their expectations, social skill instruction, and classroom-embedded use.

Indicators include: (a) Respectful talk, active listening, and turn-taking; (b) Acknowledgment of students’ backgrounds and lives outside the classroom; (c) Body language indicative of warmth and caring shown by teacher and students; (d) Physical proximity; (e) Politeness and encouragement; and (f) Fairness.

_ _ _ _ _

Domain 2b. Creating a Culture of Learning. This culture is seen in a classroom climate that has norms that reflect the importance of the educational process—to both students and the teacher. This is seen by observing students’ and teachers’ energy and enthusiasm, their dedication and persistence, and their focus on quality and understanding during instructional activities and assignments.

Teachers who are successful in creating classroom cultures where learning and hard work are valued (a) have high and realistic expectations for their students; (b) know that students are, by their nature, intellectually curious; (c) guide students toward the content of the curriculum; and (d) facilitate students’ pride and self-satisfaction as they master challenging content.

The elements of this component include that: (a) teachers convey the educational value of what the students are learning; (b) all students receive the message that, although the work is challenging, they are capable of achieving it if they are prepared to work hard; (c) teachers insist on student precision; and (d) students demonstrate energy to the tasks at hand, and take pride in their accomplishments and those of their peers.

Indicators include: (a) Belief in the value of what is being learned; (b) High expectations, supported through both verbal and nonverbal behaviors, for both learning and participation; (c) Expectation of high-quality work on the part of students; (d) Expectation and recognition of effort and persistence on the part of students; and (e) High expectations for expression and work products.

_ _ _ _ _

Domain 2c. Managing Classroom Procedures. A smoothly functioning classroom is a prerequisite to good instruction and high levels of student engagement. Teachers establish and monitor routines and procedures for the smooth operation of the classroom and the efficient use of time. Hallmarks of a well-managed classroom are that instructional groups are used effectively, noninstructional tasks are completed efficiently, and transitions between activities and management of materials and supplies are skillfully done in order to maintain momentum and maximize instructional time. The establishment of efficient routines, and teaching students to employ them, may be inferred from the sense that the class “runs itself.”

The elements of this component are: (a) teachers help students to develop the skills to work purposefully and cooperatively in groups or independently, with little supervision from the teacher; (b) transitions from different types of activities (e.g., large group, small group, independent work) involve little loss of time as students move efficiently from one activity to another; (c) teachers have all of the materials they need to teach close at hand, and they have taught students to implement routines for distribution and collection of materials with a minimum of disruption; (d) little instructional time is lost in activities such as taking attendance, recording the lunch count, etc.; and (e) volunteers and/or paraprofessionals (if present) are organized and managed effectively.

Indicators include: (a) Smooth functioning of all routines; (b) Little or no loss of instructional time; (c) Students playing an important role in carrying out the routines; and (d) Students knowing what to do and where to move.

_ _ _ _ _

Domain 2d. Managing Student Behavior. In order for students to be able to engage deeply with content, the classroom environment must be orderly; and the atmosphere must feel business-like and productive, without being authoritarian. In a productive classroom, standards of conduct are clear to students; they know what they are permitted to do and what they can expect of their classmates. Even when their behavior is being corrected, students feel respected; their dignity is not undermined. Skilled teachers regard positive student behavior not as an end in itself, but as a prerequisite to high levels of engagement in content.

The elements of this component are: (a) teachers have established clear expectations for student conduct and interact in preventative ways; (b) they are attuned to what’s happening in the classroom and move subtly to help students re-engage with the lesson or its related activities when necessary; and (c) teachers respond to challenging student behavior by trying, first, to understand it, and then by respecting the dignity of the student.

Indicators include: (a) Clear standards of conduct, possibly posted, and possibly referred to during a lesson; (b) the Absence of acrimony between teacher and students concerning behavior; (c) Teacher awareness of student conduct; (d) Preventive action when needed by the teacher; and (e) the Absence of misbehavior, and the consistent reinforcement of positive behavior.

_ _ _ _ _

Domain 3a. Communication with Students. Teachers communicate with students for several independent, but related, purposes. First, they convey that teaching and learning are purposeful activities; they make that purpose clear to students. They also provide clear directions for classroom activities so that students know what to do; when additional help is appropriate, teachers model these activities. When teachers present concepts and information, they make those presentations with accuracy, clarity, and imagination, using precise, academic language; where amplification is important to the lesson, skilled teachers embellish their explanations with analogies or metaphors, linking them to students’ interests and prior knowledge.

Teachers occasionally withhold information from students (for example, in an inquiry science lesson) to encourage them to think on their own, but what information they do convey is accurate and reflects deep understanding of the content. And teachers’ use of language is vivid, rich, and error free, affording the opportunity for students to hear language used well and to extend their own vocabularies.

Teachers present complex concepts in ways that provide scaffolding and access to students.

The elements of this component are: (a) the goals for learning are communicated clearly to students; (b) teachers ensure that students understand what they are expected to do during a lesson, particularly if students are working independently or with classmates, without direct teacher supervision; (c) teachers ensure that students understand the content and strategies within a lesson or activity—connecting the content to students’ interests and lives beyond school; and (d) explanations are clear, with appropriate scaffolding, and, where appropriate, anticipate possible student misconceptions.

Indicators include: (a) Clarity of lesson purpose; (b) Clear directions and procedures specific to the lesson activities; (c) Absence of content errors and clear explanations of concepts and strategies; and (d) Correct and imaginative use of language.

_ _ _ _ _

Domain 3c. Engaging Students in Learning. Student engagement in learning is the centerpiece of an effective classroom—all other components contribute to it. When students are engaged in learning, they are not merely “busy,” nor are they only “on task.” Rather, they are intellectually active in learning important and challenging content. The critical distinction between a classroom in which students are compliant and busy and one in which they are engaged is that in the latter, students are developing their understanding through what they do. That is, they are engaged in discussion, debate, answering “what if?” questions, discovering patterns, and the like. They may be selecting their work from a range of (teacher-arranged) choices, and making important contributions to the intellectual life of the class. Such activities don’t typically consume an entire lesson, but they are essential components of engagement.

Critical questions for an observer in determining the degree of student engagement are “What are the students being asked to do? Does the learning task involve thinking? Are students challenged to discern patterns or make predictions?” If the answer to these questions is that students are, for example, filling in blanks on a worksheet or performing a rote procedure, they are unlikely to be cognitively engaged.

In observing a lesson, it is essential not only to watch the teacher but also to pay close attention to the students and what they are doing. The best evidence for student engagement is what students are saying and doing as a consequence of what the teacher does, or has done, or has planned. And while students may be physically active (e.g., using manipulative materials in mathematics or making a map in social studies), it is not essential that they be involved in a hands-on manner; it is, however, essential that they be challenged to be “minds-on.”

The elements of this component are: (a) activities and assignments that promote learning, require student thinking that emphasizes depth over breadth, and encourage students to explain their thinking; (b) students who are strategically grouped for mastery-focused instruction (whole class, small groups, pairs, individuals); (c) instructional materials that are selected to engage students in deep learning; and (d) an instructional pace that keeps things moving, within a well-defined structure, facilitating student learning, reflection, and closure

Indicators include: (a) Student enthusiasm, interest, thinking, problem solving, etc.; (b) Learning tasks that require high-level student thinking and invite students to explain their thinking; (c) Students highly motivated to work on all tasks and persistent even when the tasks are Challenging; (d) Students actively “working,” rather than watching while their teacher “works;” and (e) Suitable pacing of the lesson: neither dragged out nor rushed, with time for closure and student reflection.

Summary. When teachers consistently and continuously demonstrate these skills and interactions, their classrooms are organized and predictable, expectations are clear and internalized, students are engaged and motivated, and learning is safe, interactive, and maximized.

When districts and schools provide, for new and existing teachers, explicit and ongoing professional development, coaching, and mentoring in the classroom management areas above, not only do more teachers succeed more quickly in their classrooms, but the teacher evaluation process is seen more as a professional growth vehicle, than an administrative appraisal requirement.

And, when all of this integrates together, the impact of any teacher preparation gaps in classroom management are minimized, and the issue of student inequity—at least as represented in the disproportionate treatment of students from poverty, of color, and with disabilities—begins to be functionally addressed.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

How Do We Get There?

From a school-wide perspective, classroom management must be integrated into a multi-tiered continuum that begins with (a) school climate, safety and discipline; moves through (b) classroom management, grade-level collaboration, and student-teacher interactions; and finishes with (c) students’ social, emotional, and behavioral self-management.

While there are many social-emotional learning and/or positive behavioral support frameworks—most have not been field-tested so that the science-to-practice elements that result in consistent, cross-country student, staff, and school success are unknown.

Below are the evidence-based psychoeducational components of effective school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management from Project ACHIEVE (www.projectachieve.info), a school improvement model that was designated a national evidence-based exemplar by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) in 2000.

Project ACHIEVE continues to be implemented across the country. For example, it is the implementation model for five School Climate Transformation Grants, awarded by the U.S. Department of Education; and it has received over $40 million in federal, state, and foundation grant funding over the past 40 years.

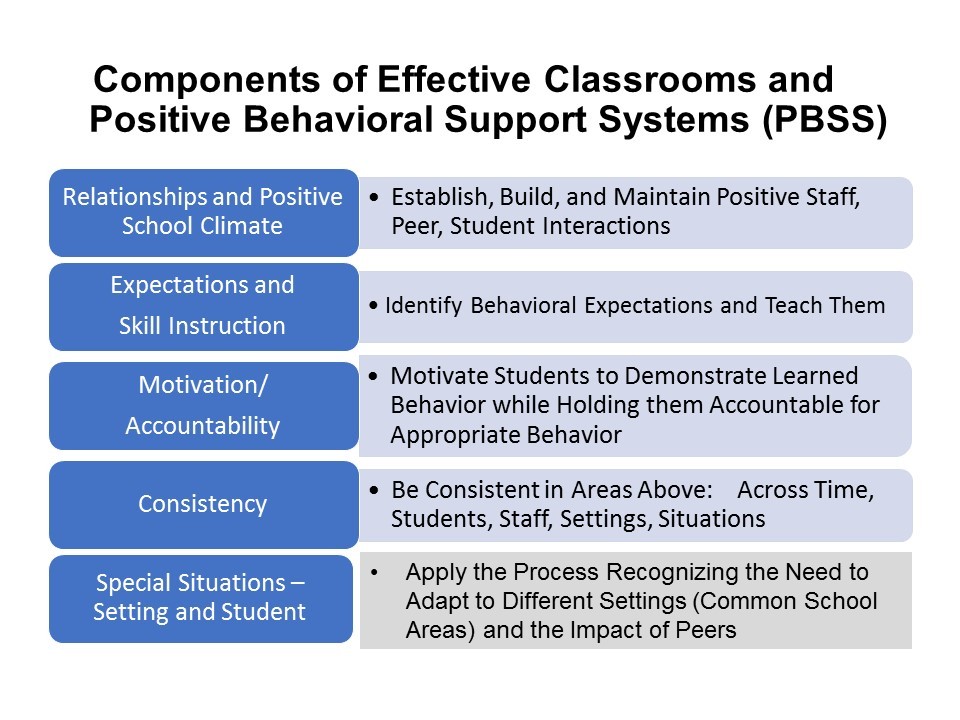

Briefly, the science-to-practice components of a successful school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management process include the following:

- Positive School Climate and Prosocial Relationships

- Clear Behavioral Expectations and Student-Focused Social Skills Instruction

- Behavioral Accountability and Motivation

- Consistent Implementation Across All Other Components

- Implementation Across Settings, Peers, and Students with Specialized Needs

From a student perspective, the primary goals of this process is for all students to learn, master, and be able to apply—from preschool through high school—the interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control, communication, and coping skills needed to be successful.

From: Knoff, H.M. (2012). School Discipline, Classroom Management,

From: Knoff, H.M. (2012). School Discipline, Classroom Management,

and Student Self-Management: A Positive Behavioral Support

Implementation Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

CLICK HERE for more information.

_ _ _ _ _

Positive Relationships and School/Classroom Climate

Effective schools work consciously, planfully, and on an on-going basis to develop, reinforce, and sustain positive and productive relationships so that their school and classroom climates support the educational process.

Critically, these relationships include: Students to Students, Students to Staff, Staff to Staff, Students to Parents, and Staff to Parents.

As reinforced in Danielson’s Framework for Teaching, this involves understanding students, their backgrounds, their histories, their strengths and weaknesses on a personal and individual level.

For minority students, this includes understanding their racial and cultural backgrounds, but being careful not to stereotype these backgrounds such that these students are not seen as individuals.

For students with disabilities, this includes understanding them beyond the “labels of their disabilities”—that is, understanding how their abilities and disabilities merge to reflect who they are and what they do physically, emotionally, attitudinally and attributionally, and behaviorally.

All of this needs to be done by all of the adults across a school, but the adults need to involve and engage the different peer groups in a school to do the same things.

_ _ _ _ _

Positive Behavioral Expectations and Skills Instruction

Students—from preschool through high school—need to be taught (just like an academic skill) the explicit social, emotional, and behavioral expectations in the classrooms and across the common areas of the school. These expectations need to be communicated in a prosocial way as “what they need to do,” rather than in a negative, deficit-focused way as “what they do not need to (or should not) do.”

Indeed, teachers and administrators will have more success teaching and telling students to (a) walk down the hallway (rather than “Do not run”); (b) raise your hand and wait to be called on (rather than “Don’t blurt out answers”); (c) accept a consequence (rather than “Don’t roll your eyes and give me attitude”).

In addition, these expectations need to be behaviorally specific—that is, we need to describe exactly what we want the students to do (e.g., in the hallways, bathrooms, cafeteria, and on the bus).

Indeed, it is not instructionally helpful to talk in constructs—telling students that they need to be “Respectful, Responsible, Polite, Safe, and Trustworthy.” This is because each of these constructs involve a wide range of behaviors. At the elementary school level, students really do not functionally or behaviorally understand these higher-ordered thinking constructs. At the secondary level, students may interpret these constructs (and their many inherent behaviors) differently than staff.

Thus, and as above, we need to teach all students the behaviors that we want them to demonstrate. Critically, this is done by teaching these students—from preschool through high school—social skills and behaviors (just like we teach a basketball the different plays in our offensive playbook). This instruction is done by the general education classroom teachers, who are then supported by the mental health specialists who work with students who need modified, smaller group, or more intensive attention.

Finally, the teaching approach required must be grounded in social learning theory. Specifically, we need to teach students the social skill behaviors step-by-step, demonstrate the steps to them, give them opportunities to practice with explicit feedback, and then to help them to apply (or transfer) their new skills to “real-world” situations.

_ _ _ _ _

Student Motivation and Accountability

For the skill instruction described above to “work,” students need to be motivated and held accountable for demonstrating positive and effective social, emotional, and behavioral skills.

Scientifically, motivation is based on two component parts: Incentives and Consequences. But to work, these incentives and consequences must be meaningful and powerfulto the students (not just to the adults in a school).

Too often schools create “motivational programs” for students that involve incentives and consequences that the students couldn’t care less about. Thus, it looks good “on paper,” but it holds no weight in reality—at least from the students’ perspectives. Thus, student involvement in the development of an effective motivational system is essential.

But beyond this, this is not about frameworks or programs, it is about effective practices. And in order to established successful and sustained classroom management and student self-management practices, teachers need a classroom discipline accountability “road map.”

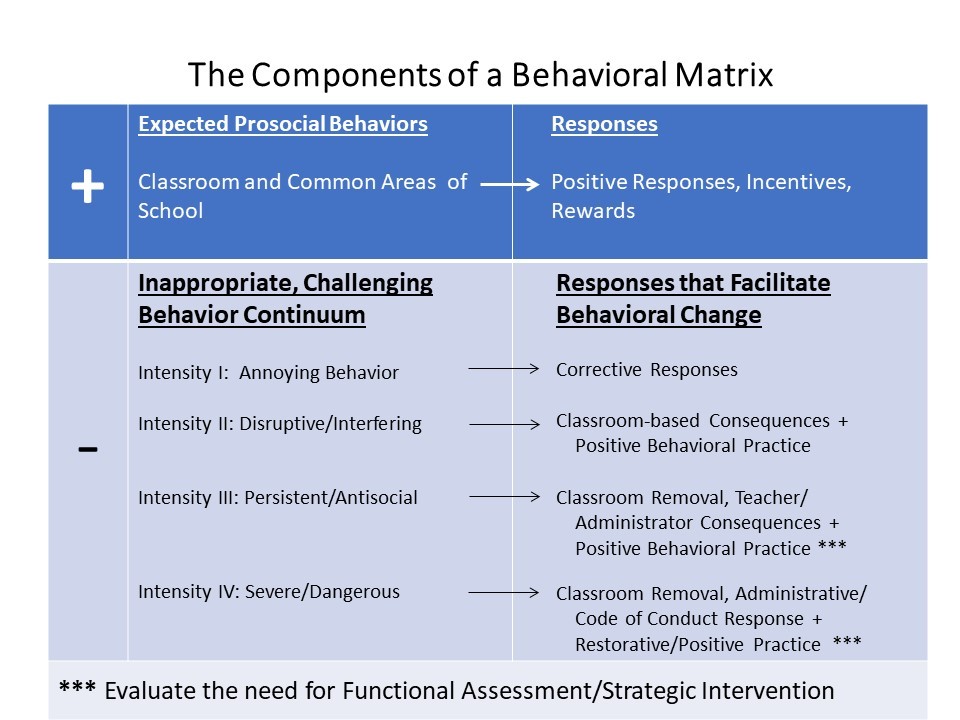

For us, this road map is called the Behavioral Matrix, and it is the “anchor” to a school’s behavioral accountability and progressive classroom management system. Critically, every Behavioral Matrix has four research-based components that address appropriate behavior, and that help teachers respond strategically to inappropriate behavior (see the Figure below). Relative to the latter, and consistent with Danielson, teachers use the Matrix to understand why students are behaving inappropriately so that this behavior is eliminated in the future and replaced with appropriate behavior.

The first two components of the Behavioral Matrix specify (a) the behavioral expectations in the classroom connected (b) with positive responses, motivating incentives, and periodic rewards.

The third and fourth components identify four progressive “Intensity Levels” of inappropriate behavior, connected with corresponding corrective responses, in and out-of-classroom consequences, and administrative actions. These components make students aware of how inappropriate behavior will be addressed when it occurs—thereby (a) motivating student to avoid these responses by demonstrating appropriate behavior, or (b) preparing students for the consequences or administrative responses if they choose to demonstrate inappropriate behavior.

Critically, when students and staff are taught and begin to internalize the Behavioral Matrix and its processes, student motivation and self-management increases, as does effective classroom management and teacher consistency.

_ _ _ _ _

Consistency

Consistency is a process. It would be great if we could “download” it into all students and staff. . . or put it in their annual flu shots. . . but that’s not going to happen.

Consistency needs to be “grown” experientially over time and, even then, it needs to be sustained in an ongoing way. It is grown through effective strategic planning with explicit implementation plans, good communication and collaboration, sound implementation and evaluation, and consensus-building coupled with constructive feedback and change.

It’s not easy. . . but it is necessary for school and classroom management success. And it is especially important for students from minority backgrounds and students with disabilities (SWDs).

In fact, as noted above, studies have clearly demonstrated that some of the disproportionality in our schools occurs because some staff send minority students and SWDs to the Principal’s Office for the same (mild to moderate) behavioral offenses that they handle in the classroom with their white students. Said in “Behavioral Matrix” terms, these teachers are making Intensive III (Persistent/Antisocial Behavior) decisions when minority students and SWDs are demonstrating Intensive I (Annoying) or II (Classroom Disruptive) behaviors.

But relative to school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management, consistency must occur across all four of the interdependent components in this process.

That is, in order to be successful, staff (and students) need to (a) demonstrate consistent prosocial relationships and interactions—resulting in consistently positive and productive school and classroom environments; (b) communicate consistent behavioral expectations, while consistently teaching and practicing them; (c) use consistent incentives and consequences, while holding student consistently accountable for their appropriate behavior; and then (d) apply all of these components consistently across all of the settings, circumstances, and peer groups in the school.

Moreover, consistency occurs when staff are consistent (a) with individual students, (b) across different students, (c) within their grade levels or instructional teams, (d) across time, (e) across settings, and (f) across situations and circumstances.

Critically, when staff are inconsistent, students feel that they are treated unfairly, they sometimes behave differently for different staff or in different settings, they can become manipulative—pitting one staff person against another, and they often emotionally react—some students getting angry with the inconsistency, and others simply withdrawing because they feel powerless to change it.

Said a different way: Inconsistency undercuts student accountability, and you don’t get the consistent social, emotional, or behavioral self-management that you want in class or across the school.

_ _ _ _ _

Implementation Across All Settings, Peers, and Specialized Needs

The last component of the school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management model focuses on the application of the previous four components to all of the settings, situations, circumstances, and peer/adult interactions in the school.

Relative to the first area, it is important to understand that the common areas of a school are more complex and dynamic than the classroom settings. Indeed, in the hallways, bathrooms, buses, cafeteria, and on the playground (or playing fields), there typically are more multi-aged or cross-grade students, more and varied social interactions, more space or fewer physical limitations, fewer staff and supervisors, and different social demands.

As such, the positive student social, emotional, and behavioral interactions that occur more easily in the classroom often are more taxed in the common school areas—and thus, need more specialized training.

Relative to peers, it is important to understand that the peer group is often a more dominant social and emotional “force” for individual students than the adults in a school. As such, the school’s approaches to student self-management must be consciously generalized and applied (relative to climate, relationships, expectations, skill instruction, motivation, and accountability) to help prevent peer-to-peer teasing, taunting, bullying, harassment, hazing, and physical aggression.

This is done by involving the different peer groups in a school in group “prevention and early response” training, and motivating them—across the entire school—to take the lead relative to prosocial interactions.

Truly, the more the peer group can be trained, motivated, and reinforced to do “the heavy prosocial lifting,” the more successful the staff and the school will be relative to positive school climate and consistently safe schools. And, the more successful students will be relative to social, emotional, and behavioral self-management.

Finally, every school has students with significant unique or idiosyncratic needs. These students, for example, may have medical or disability-related issues, they may have experienced devastating individual or family events, they may be homeless or living in homes with significant income issues.

For these students, multi-tiered services, supports, strategies, or interventions are often the “safety net” that they need to be socially, emotionally, or behaviorally successful. Schools need to have this multi-tiered system of supports in place and available to all students—but especially, these students—so that they receive what they need to succeed in their classrooms, and with their teachers and peers.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

This Blog reviewed two major reports released within the past two weeks: (a) the National Council on Teacher Quality’s 2020 Teacher Prep Review: Clinical Practice & Classroom Management; and (b) the UCLA Civil Rights Project’s Lost Opportunities: How Disparate School Discipline Continues to Drive Difference in the Opportunity to Learn.

After analyzing the results in these reports, we concluded that:

- District cannot depend on teacher training programs to prepare their graduates in the areas of classroom management.

Thus, Districts must provide the hands-on professional development, training, and supervision needed to ensure that all of their teachers learn, master, and consistently demonstrate the classroom management skills needed for student and teacher success.

- Poor classroom management skills can negatively impact classroom climate, student-teacher and student-student relationships and interactions, student engagement and motivation to attend, teacher engagement and staying in the profession, and student behavior and disproportionate office discipline referrals and suspensions for students of color and students with disabilities.

- Relative to the latter area, and at this time when the racial inequities of the past (along with inequities related to students’ socio-economic and disability status) need to be explicitly addressed, schools and districts must target the area of school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management in their professional development, coaching, and mentoring programs.

To facilitate this, we then used Charlotte Danielson’s Framework for Teaching to highlight the domains and components most relevant to effective classroom management. But, knowing that Danielson is used by many districts across the country for teacher evaluation, we emphasized that our discussions was focused on teacher skills and growth, not teacher appraisal and oversight.

Finally, we put the entire discussion into a school-wide systemic context by describing the evidence-based psychoeducational components of effective school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management from Project ACHIEVE (www.projectachieve.info), a school improvement model that was designated a national evidence-based exemplar by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) in 2000.

These science-to-practice components are:

- Positive School Climate and Prosocial Relationships

- Clear Behavioral Expectations and Student-Focused Social Skills Instruction

- Behavioral Accountability and Motivation

- Consistent Implementation Across All Other Components

- Implementation Across Settings, Peers, and Students with Specialized Needs

As noted earlier, when teachers consistently and continuously demonstrate effective classroom management skills and interactions, their classrooms are organized and predictable, expectations are clear and internalized, students are engaged and motivated, and learning is safe, interactive, and maximized.

When districts and schools provide explicit and ongoing professional development, coaching, and mentoring in classroom management, not only do more teachers succeed more quickly in their classrooms, but the teacher evaluation process is seen more as a professional growth vehicle, than an administrative appraisal requirement.

And, when all of this integrates together, the impact of any teacher preparation gaps in classroom management are minimized, and the issue of student inequity—at least as represented in the disproportionate treatment of students from poverty, of color, and with disabilities—begins to be functionally addressed.

_ _ _ _ _

As always, I hope that this Blog has provided some explicit and practical guidance and direction in a critical area of school and classroom need.

For those schools and teachers who are successful in this area, I applaud you. But for the schools and teachers who know that they “can do better,” this Blog provides the evidence-based roadmaps toward growth and improvement.

I appreciate the time that you invested in reading this Blog, and hope that you, your students, your colleagues, and your community continues to be safe and protected during these challenging times.

Please feel free to send me your thoughts and questions.

And please know that I continue to work—especially virtually—with districts and schools across the country. . . helping them to maximize their school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management practices and activities.

Feel free to contact me at any time. The first one-hour conversation with your team is complimentary.

Best,