For Some Students, There Will Be No COVID-19 Slide

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

The pandemic clearly is not over.

In fact, over the past two weeks, the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths have increased on a day-to-day basis in the United States, and many cities and new geographic areas are experiencing record high incidents.

And yet, “school”. . . in one form or another. . . will “open” come Fall. And given this, virtually every administrator in our country has begun a re-opening and re-entry planning process.

As we have discussed in recent Blog articles, at the core of this process is the implicit or explicit post-pandemic re-entry model or models that will be used by a district and its schools. This is significant because each re-entry model has strengths and weaknesses, and every selection will impact the resulting functional, logistical, instructional, and staffing decision and plan. This, in turn, may significantly affect all or some students, and their academic and social, emotional, behavioral, and mental health status and needs.

Relative to my Blogs, when the pandemic closed all of our schools in March, my bimonthly Blog articles began to directly address COVID-19’s impact on the short- and long-term academic and social, emotional, behavioral, and mental health status of our students, staff, schools, and systems. While I integrated the research and wisdom of others, the contexts, implications, and interpretations in these Blogs most reflected my forty years of field-based experience, and my school psychological perspective.

This perspective is not more important than others’ perspectives. But it differs in important ways from the majority of the educators nationwide. . . who are focusing more predominantly on administration and/or instruction.

Indeed, the difference is that psychology is the foundation to understanding how learning occurs, and how to maintain and motivate the social, emotional, and behavioral interactions that facilitate student learning and learning outcomes.

Said a different way: It’s great to have a great re-entry plan. But a plan is only as good as its implementation. And to implement a great plan, students, staff, administrators, and parents/guardians—individually and collectively—need to have the emotional readiness, the belief and the confidence, and the skills and motivation to consistently execute the plan.

And so, it is essential to integrate a psychological science-to-practice perspective in order to execute a district or school’s administrative and instructional plans effectively. . . and to—hopefully—maximize everyone’s success.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Re-Visiting the Fall Post-Pandemic Academic and Instruction Process

This two-part Blog Series is addressing what schools need to consider now as they plan for their students’ academic re-entry this Fall.

In Part I, we addressed why (and how) schools should validly assess—as soon as possible when students return to school—the functional, mastery-level status of all students in literacy, mathematics, and writing/language arts. Here, we recommended an assessment process with the following steps (see Part I for the complete discussion):

- Identify the Power or Anchor Standards in literacy, mathematics, and writing/language arts at each grade level that are most essential for students to learn and that, typically, represent the foundational or prerequisite knowledge and skills that generalize to help students to learn and master the content in other, related standards.

_ _ _ _ _

- From the Power or Anchor Standards, identify the knowledge, content, information, and skill-specific test items needed in each grade level’s literacy, mathematics, and writing/language arts assessments that most accurately evaluate students’ current functional learning and mastery status.

_ _ _ _ _

- Create, administer, and score an Academic Assessment Tool with these items in each academic area to determine students’ grade-level functioning—regardless of their current grade-level standing.

_ _ _ _ _

- Complement (and re-validate) these assessments’ results with formal and informal classroom- and curriculum-based teacher assessments that are completed during instruction, through independent assignments and work samples, and based on in-class portfolios, projects, or tests.

_ _ _ _ _

[CLICK HERE for Part I of this Blog Series]

We then recommended that the assessment results be used to identify groups of students who are functioning above, at, below, or well-below their current grade-level placements.

Here, we suggested that students scoring (a) 1.5 standard deviations above the average functioning of their grade-level peers—in literacy, mathematics, and writing/language arts, respectively—be identified as functioning above their current grade placement; (b) between -1.0 and 1.5 standard deviations to be functioning at grade-level; (c) between -2.0 and -1.0 standard deviations to be below grade-level; and (d) below -2.0 standard deviations to be well-below grade-level.

Next, we recommended that schools pool all of the assessment data for the students at each grade level, completing a “StoryBoard” process to determine the best instructional groups to assign each student to in each academic area. These assignments would then determine the best way to organize students—across the three academic areas—into classroom cohorts.

Significantly, this StoryBoard process should also identify the students who need specific multi-tiered services, supports, and interventions. . . which should eventually result in decisions as to (a) what support staff will work with which students and grade levels of teachers, and (b) what additional instructional or technological resources will be used with which students.

Finally, in Part I, we discussed how (and why) to organize students who are functioning within one grade level of their respective grade placements into Homogeneous Skill Groups and/or Heterogeneous Comprehension or Applied Groups. We provided a Third Grade example with literacy results, integrating the data into one of the six national models that most districts will use when students return to school in the Fall.

_ _ _ _ _

In this Part II of the Series, we will discuss how to use the assessment results to address the academic progress and enrichment of students who are “above” their grade-level standing, and the academic gaps of students who are below and well below their grade-level placements.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Teaching Students Who are Academically Above Average

Without overgeneralizing, students functioning above their grade level placements in literacy, mathematics, and/or writing/language arts have probably been ahead of the game for a number of years. And while they may have received phenomenal virtual instruction during the months of this pandemic, they also probably (a) took advantage of and were able to learn from this instruction and approach; (b) are self-motivated, and competently engaged in self-instruction; and/or (c) have parents and/or peers that motivated or facilitated their learning and mastery.

An important point here is that some students will not experience a pandemic learning loss or slide. This is why we have emphasized, especially during this Blog Series, the importance of collecting current (in the Fall) assessment data. . . and not assuming or guessing students’ academic status.

But when these above average students return to school this Fall, the ultimate question is:

What instructional staff and materials, and what learning environments and approaches, will maintain and extend these above average students’ learning, enrichment, and progress?

Critically, the answer to this question will depend on the age and grade levels of these students (e.g., lower or upper elementary, middle or high school levels, respectively), as well as how many of their peers are also functioning at above average academic levels.

In addition, it is important to recognize that these students may not be advanced in all or most of the core academic areas. For example, some students may be functioning above grade level in one academic area, and atgrade level (or even below) in all other areas.

This, once again, reinforces the importance of StoryBoarding all of the students at each grade level and in each academic area, and then looking across the grade levels at all the students in the same school.

_ _ _ _ _

From this StoryBoarding process, strategic decisions about the best instructional groups for these students can be made. . . as we formally begin the Fall semester.

For example, at the elementary school level, decisions relative to putting above average students into Homogeneous Skill Groups and/or Heterogeneous Comprehension or Applied Groups should be made.

[Please review this discussion in Part I of this Blog Series].

This could include teaching a cluster of students, functioning a grade level above their current chronological placement in one (or more) academic areas, with on-grade-level students at the next grade level in a multi-aged group—if this is socially and emotionally appropriate.

For example, Grade 2 students functioning at the 3rd Grade level in Reading, could be taught in a multi-aged Grade 2-3 cluster (that is, with 3rd Grade students who are reading “at grade level”). Grade 4 students functioning at the 5th Grade level in Mathematics, could be taught in a multi-aged Grade 4-5 cluster (that might also include Science) with 5th Grade students who are performing “at grade level” in math.

In other words, enrichment aside, elementary students who are functioning above their grade levels in a specific academic area can simply be placed, for the skill part of their instruction, with “older” students who are functioning at the same level of the curriculum’s scope and sequence.

This can be easily coordinated when the adjacent grade levels in a school (Kindergarten and 1st Grade, Grades 2 and 3, Grades 4 and 5—if not the entire school) have common reading or mathematics instructional time blocks in their schedules.

While moving students safely and effectively, relative to social distancing, will still need to be factored into these arrangements, why would a school sacrifice the academic progress of its students by arranging its classrooms solely based on one-dimensional COVID-19 guidelines—especially when other configurations (relative to both classroom schedules and student grouping patterns) are possible (and needed)?

Surely, we can walk and chew gum at the same time!

Of course, another way to address specific students’ above average academic skills and mastery—especially in a larger school—is to pool all of these students in the same grade level together for skills-based instruction, or to organize each classroom so that teachers can effectively differentiate their instruction and provide instruction for these students’ at their functional skill levels. But all of this takes valid, current data and effective, big-picture planning.

_ _ _ _ _

At the Middle School and High School levels, if the schedules allow and teaching staff are available, advanced students can simply be scheduled into more advanced courses.

Indeed, if socially and emotionally appropriate, why can’t a Middle School—that uses a criterion-based skill mastery approach to assess student progress—organize some of its classes in multi-aged cohorts (just as some High School classes have a mix of sophomore, juniors, and seniors)?

I can still remember a Middle School that served a high percentage of students from poverty in the Baltimore City School District that organized its students into classes where one-third of the students were 6th, 7th, and 8th graders. The students stayed together for all three of their years in the school, and they took literacy/language arts, science, social science, and Expeditionary Learning together. The only class that was organized in skill-based groups was mathematics, where students learned at their functional skill levels in homogeneous groups.

This was over twenty years ago, and the students were some of the most accomplished students in the District. In fact, the school had a waiting list of students wanting to get in, discipline and behavior management issues were incredibly low, and the school’s positive climate was comparably as high.

My example aside, if a particular school’s schedule is not flexible, perhaps (given the discussion above) the above average secondary students can (continue to) learn effectively through a blended model of virtual and live instruction and coaching.

If this is true, perhaps certain staff can work with a number of advanced students who are learning somewhat different skills at somewhat different places in the curriculum. . . in the literacy, mathematics, and/or writing/language arts. . . during the same class period.

And let’s remember the dual enrollment high school/college option. But here, why can’t a combined senior/freshman college course be open to juniors (or even sophomores) if they are ready for it and have a high probability of learning and success?

Just think about it! Many schools across the country just concluded three months of virtual instruction. If many schools are now moving toward a blended or alternating on-site/virtual instruction model this Fall, why would they not take the students who will most benefit from this model, and program them into this format right from the beginning? This, then, might free up other resources and staff to work more directly with the students who do not respond as well to these approaches.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Teaching Students Who are Academically Below or Well Below their Grade-Level Placements

Despite the pandemic, students who are identified this Fall as being below or well below grade-level functioning in literacy, mathematics, and/or writing/language arts need to be evaluated within the context of an effective and science-to-practice multi-tiered systems of supports. Essentially, this means that a data-based functional assessment of their educational history, learning conditions, speed of mastery, and current status needs to be completed for each student.

This assessment is important because, for example, five students who are all two years below grade level in reading could have five different learning patterns and progressions, and five different root causes explaining their academic gaps. Only by differentiating among these different root causes can these students be individually scheduled into the best instructional groups with the most effective teachers so that they can receive the services, supports, strategies, and interventions that they need.

Critically, except for new students to the district, is it unlikely that district or school personnel will be surprised by the identities of the below and well below average students this coming Fall. Moreover, while their learning gaps may be somewhat larger, it also is unlikely that the pandemic and the need for “home-schooling” caused these students’ problems.

Thus, if they have been successful in the past, schools may only need to transfer and adapt these students’ programs from last year to this year.

However, if they have not been successful—or if critical conditions have changed, schools may use the pandemic-driven need to modify instruction for all students as a leverage point to provide these students the programs that they need and that—from an equity perspective—they deserve.

And so, when these below and well below average students return to school this Fall, the ultimate question is:

What instructional staff and materials, and what learning environments and approaches, will strengthen and accelerate these below and well below average students’ learning, enrichment, and progress?

NOTE that this question is remarkably similar to the question asked above for above average students. And NOTE, that these students also need enrichment—especially as a way to motivate and engage them in an educational enterprise that often frustrates and knocks them down.

_ _ _ _ _

In the next two sections below, we provide two research-to-practice blueprints to help answer the question above. The first blueprint focuses on a continuum of services, supports, and interventions for students who are academically struggling. The second blueprint addresses some potential grouping and instructional patterns for these students.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

The Positive Academic Supports and Services Continuum

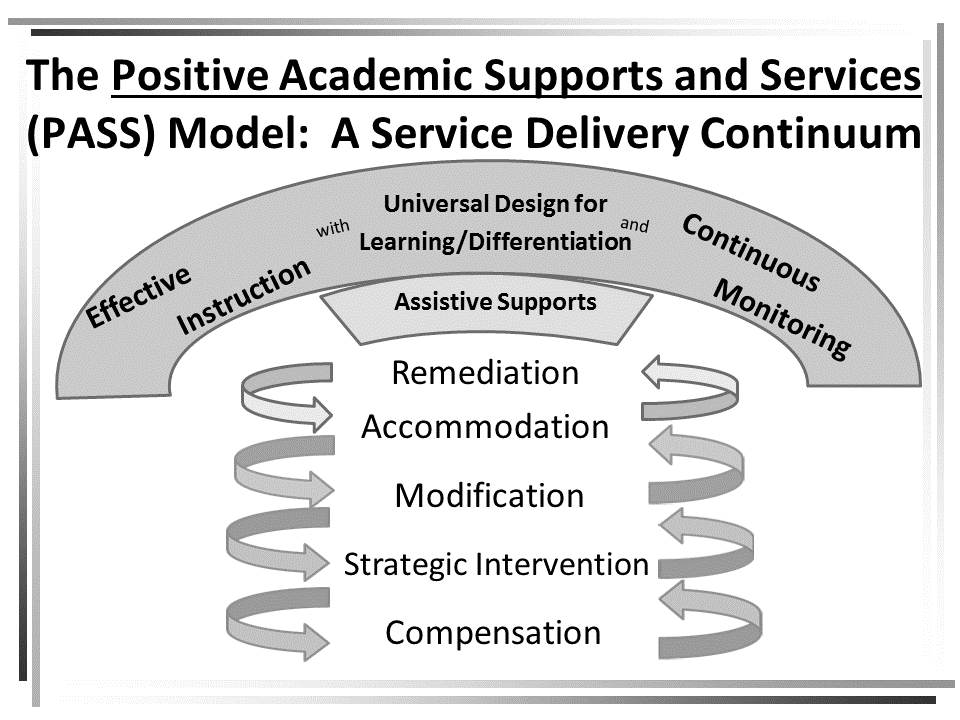

Based on the data-based functional assessment of the root causes of a student’s academic struggles, an effective multi-tiered system of supports links the root cause results to high probability of success services, supports, strategies, and interventions. One way to conceptualize these services and supports is through a research-to-practice Positive Academic Supports and Services (PASS) blueprint or continuum (see the Figure below).

The foundation to the PASS blueprint is effective and differentiated classroom instruction where teachers use and continuously evaluate (or progress monitor) evidence-based curricular materials and approaches that are matched to students’ learning styles and needs. When students are not consistently learning and mastering academic skills after a reasonable period of effective instruction, practice, and support, the data-based, functional assessment, problem-solving process is used to determine the root causes of the problem.

Results then are linked to different instructional or intervention approaches that are organized along the following PASS continuum:

- Assistive Supports involve specialized equipment, technologies, medical/physical devices, and other resources that help students, especially those with significant disabilities, to learn and function—for example, physically, behaviorally, academically, and in all areas of communication. Assistive supports can be used anywhere along the PASS continuum.

- Remediation involves strategies that teach students specific, usually prerequisite, skills to help them master broader curricular, scope and sequence, or benchmark objectives.

- Accommodations change conditions that support student learning—such as the classroom setting or set-up, how and where instruction is presented, the length of instruction, the length or timeframe for assignments, or how students are expected to respond to questions or complete assignments. Accommodations can range from the informal ones implemented by a classroom teacher, to the formal accommodations required by and specified on a 504 Plan (named for the federal statute that covers these services).

- Modifications involve changes in curricular content—its scope, depth, breadth, or complexity.

Remediations, accommodations, and modifications typically are implemented in general education classrooms by general education teachers, although they may involve consultations with other colleagues or specialists to facilitate effective implementation. At times, these strategies may be implemented in “pull-out,” “pull-in,” or co-taught instructional skill groups so that more students with the same needs can be helped.

If target students do not respond to the strategically-chosen approaches within these three areas, or if their needs are more significant or complex, approaches from the next two PASS areas may be needed:

- Strategic Interventions focus on changing students’ specific academic skills or strategies, their motivation, or their ability to comprehend, apply, analyze, synthesize, or evaluate academic content and material. Strategic Interventions typically involve multidisciplinary assessments, as well as formal Academic Intervention or Individualized Education plans (AIPs or IEPs).

- Compensatory Approaches help students to compensate for disabilities that cannot be changed or overcome (e.g., being deaf, blind, or having physical or central nervous system/neurological disabilities). Often combined with assistive supports, compensatory approaches help students to accomplish learning outcomes, even though they cannot learn or demonstrate specific skills within those outcomes. For example, for students who will never learn to decode sounds and words due to neurological dysfunctions, the compensatory use of audio or web-based instruction and (electronic) books can still help them to access information from text and become knowledgeable and literate. Both assistive supports and compensatory approaches are “positive academic supports” that typically are provided through IEPs.

While there is a sequential nature to the components within the PASS continuum, it is a strategic and fluid—not a lock-step—blueprint. That is, the supports and services are utilized based on students’ needs and the intensity of these needs.

For example, if reliable and valid assessments indicate that a student needs immediate accommodations to be successful in the classroom, then there is no need to implement remediations or modifications just to “prove” that they were not successful. In addition, there are times when students receive different supports or services on the continuum simultaneously. For example, some students need both modifications and assistive supports in order to be successful. Thus, the supports and services within the PASS are strategically applied to individual students.

Beyond this, while it is most advantageous to deliver needed supports and services within the general education classroom (i.e., the least restrictive environment), other instructional options could include co-teaching (e.g., by general and special education teachers in a general education classroom), pull-in services (e.g., by instructional support or special education teachers in a general education classroom), short-term pull-out services (e.g., by instructional support teachers focusing on specific academic skills and outcomes), or more intensive pull-out services (e.g., by instructional support or special education teachers).

These staff and setting decisions are based on the intensity of students’ skill-specific needs, their response to previous instructional or intervention supports and services, and the level of instructional or intervention expertise needed. Ultimately, a primary goal of the PASS model is to provide students with early, intensive, and successful supports and services that are identified through the problem-solving process, and implemented with integrity and needed intensity.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Students with Significant Academic Skills Gaps: Connecting Their Needs to Closing-the-Gap Options

This section is adapted from an earlier Blog that addressed ways to academically program for secondary-level students with significant knowledge and skill gaps. Because scheduling, staffing, and resource management issues are more complex at the secondary level (than the primary level), the academic needs of students functioning below and well below their current grade-levels are addressed below. Elementary-level educators can interpolate the discussion to students at their grade levels.

_ _ _ _ _

From a multi-tiered perspective—and as discussed above, the results of the data-based problem-solving process is essential to quantify, analyze, and hopefully close the academic gaps that exist for below and well below grade-level functioning students. Just like the diagnostic process that a doctor completes when you are sick—before prescribing the medicine and other facets of your medical intervention—data-based problem-solving is a necessity if we are going to implement effective, high-probability-of-success academic interventions.

Unfortunately, many schools have some student data, but it typically is descriptive and not diagnostic data. At times, these schools use these data to inadvertently play “intervention roulette”—throwing “interventions” at problems without really knowing the root causes as to why they exist.

I am critiquing, not criticizing, these schools. More often than not, they are doing what they were told to do by their “experts.”

_ _ _ _ _

But, critically, at the point of intervention, there still are times when schools hit the proverbial “fork in the road.”

This occurs, specifically, when students’ prerequisite academic skills are so low that everyone knows that they have virtually no chance of passing the next middle or high school course.

Here, most schools use one of the following Options:

- Option 1. Schools schedule the “not-ready-for-prime-time” students into their existing course sequences, and teach them at their grade levels—hoping that effective differentiated instruction will close the existing achievement gaps at the same time that the students learn and master the new, course-related content and skills.

_ _ _ _ _

- Option 2. Schools use Option 1—scheduling the “not-ready-for-prime-time” students into their existing course sequences, and then they offer/provide tutors or tutoring (usually before or after school) to supplement the instruction and “close” the gaps.

This, unfortunately, rarely works because (a) the students are too far behind to benefit from tutoring—that is, there simply is not enough time available to close the long-standing gaps; (b) the tutoring is provided by paraprofessionals who do not have the expertise to implement the strategic interventions needed; (c) the tutoring is not coordinated with the general education teachers or aligned to the curricula being taught in the core classes; and/or (d) the student does not attend the tutoring (enough) due to transportation, studying for other classes, extracurricular activities, or simply fatigue, frustration, or resignation.

_ _ _ _ _

- Option 3. Schools “double-block” the students—scheduling them into the existing course sequences while also giving them an additional academic period a day (or less) to remediate their skills gaps.

Here, they are hoping that the remediation period will “catch the students up,” while they simultaneously complete the grade-level courses so they can accrue their credits. But many times, the teachers teaching these two separate courses do not communicate, the curricula and interventions are not coordinated, and the students still do not have the skills to pass the grade-level course.

_ _ _ _ _

- Option 4. Here, schools “double-block” the students, but the students have the same teacher for both blocks. This allows the teacher to follow the grade-level course’s syllabus, but s/he can spend time remediating students’ prerequisite skills gaps so they are prepared for and can learn and master the grade-level course material.

In addition, this also gives the teacher the time needed to adapt his or her instruction for students who require, for example, (a) more concrete and sequential instruction, (b) more positive practice repetition, or (c) assistive supports or accommodations to learn the material.

In reality, based on their data-based student analyses, schools may need to have Options 1, 3, and 4 available in order to maximize the learning and mastery of different students with different learning histories and instructional needs. But these options, depending on their root causes, may not be viable for below and, especially, well below grade-level students.

Thus, Option 5 may be necessary.

Option 5 is for students who have no chance of passing their next middle or high school course, even with Options 1, 3, or 4 above, because their prerequisite academic skills are so low. Critically, for students who do not have a disability and, therefore, do not qualify for services through an Individualized Education Plan (IEP; IDEA) or a 504 Plan (Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act), Option 5 may be the best option.

Indeed, the most common root causes for these students’ academic struggles include the following:

- There were significant instructional gaps during the student’s educational history such that the student did not have the opportunity to learn and master essential academic skills.

This includes, for example, students who were (a) home-schooled, (b) had new teachers who were unprepared to teach, (c) had long-term substitute or out-of-field teachers for lengthy periods of time, or (d) were in classrooms with too many different student skill groups for the teachers to effectively teach.

_ _ _ _ _

- There were significant curricular gaps during the student’s educational history such that the student did not have the opportunity to learn and master essential academic skills.

This includes, for example, (a) schools without the appropriate evidence-based curricula or curricular materials to support teachers’ goals of effectively differentiating instruction; (b) schools where teachers—at the same grade level—were teaching the same content but with different algorithms, rubrics, or skill scripts that were then not reinforced by the next year’s teachers—especially as they “inherited” a mix of students who were taught specific skills in vastly different ways; or (c) schools that adopted grade-level curricula that were not aligned with state academic standards, and that did not articulate with the curricular expectations at the next grade level.

_ _ _ _ _

- The schools, attended by the student during his/her educational history, had an absent, inadequate, or ineffective multi-tiered system of supports that did not address his or her academic needs.

_ _ _ _ _

- The student was taught, over a long or significant period of time, in a school or classroom where the relationships or climates were so negative (or negatively perceived by him/her) that they impacted his/her long-term academic engagement, motivation, attendance, and access or ability to learn.

_ _ _ _ _

- The student had known or has newly-diagnosed (due to the root cause analysis) biological, physiological, biochemical, neurological, or other physically- or medically-related conditions or factors that significantly impacted his or her learning and mastery, or the speed that s/he learns and masters new skills.

_ _ _ _ _

- The student had (and may still have) frequent or significant personal, familial, or other traumatic life events or crises that impacted his or her academic engagement, motivation, attendance, and access or ability to learn.

_ _ _ _ _

- The student’s skill gaps created such a level of frustration that the resulting social, emotional, or behavioral reactions by the student (along an “acting out” to “checking out” continuum) overshadowed the original and present academic concerns—resulting in the absence of (or the student’s avoidance of) needed services or supports.

_ _ _ _ _

The vast majority of these root causes point to the fact that students who will most benefit from an Option 5 approach are students who did not have the opportunity to originally learn and master the academic skills that are now embedded in their significant skill gap.

At the same time, many of these student will need additional social, emotional, or behavioral services and supports so that the academic interventions can be successful.

Even more critically, the students’ motivation and positive, active engagement in the Option 5 course(s) and classroom will be a key factor in determining their success. This will be especially true at the high school level, when students are confronted with the reality of a four-plus year high school career (which may look worse than dropping out or going for a GED).

All of this is to say that not all students who could potentially benefit from an Option 5 approach should or will choose it. For Middle School students, this Option involves less student choice, and more “pressure” on the school to keep the students well-integrated with their peers and in other grade-level classes. For High School students, they need to see realistic ways that they can pass their high school courses after or as their skill deficits are remediated.

_ _ _ _ _

What is Option 5?

Option 5 involves scheduling students into a course (or a double-blocked course) in their academic area(s) of deficiency that targets its focus and instruction on the students’ functional, instructional skill level. That is, the course takes students from their lowest points of skill mastery (regardless of level), and moves them flexibly through each grade level’s scope and sequence as quickly as they can master and apply the material.

This should be an instructional—not a credit recovery or computer/software-dependent—course with a teacher qualified both in instruction and intervention.

Moreover, this should be the students’ only course in the targeted academic area, and the course instructors are responsible for making the content and materials relevant to the grade level of the student, even as they are teaching specific academic skills at the students’ current functional skill levels.

Thus, students are not concurrently taking a grade-level course in the same academic area (as in Options 1 through 4 above). Moreover, the teachers in these students’ science, social science, or other courses also know the students’ current functional skill levels—differentiating their instruction as needed, while providing additional supports, so that the students’ areas of academic weakness do not negatively impact their learning in these “lateral” courses.

_ _ _ _ _

For example, if a group of rising 9th grade students have mastered their math skills only at the beginning fourth grade level, their Option 5 math class for that quarter, semester, or year would begin its instruction at the fourth grade level of the state or district’s preschool through high school math scope and sequence, and progress accordingly as a function of their learning and mastery.

The students would not concurrently take a 9th grade math course, and the Option 5 teachers would be responsible for making the math content and materials relevant to a 9th grade learner, even as the mathematical skills are being taught at a 4th grade level.

In reading, the Option 5 teachers would use, for example, high-interest (9th grade content and focus)/low vocabulary (4th grade) books, stories, or materials so that the students can build their vocabulary and comprehension skills in a sequential and progressive way.

_ _ _ _ _

Ultimately, Option 5 succeeds when its services, supports, strategies, and interventions are matched to the root causes that explain why struggling students’ significant academic skill gaps exist. Relative to this Fall and in the context of the pandemic, virtually all of these students already existed.

If we do not effectively program these students for academic success, then we run the risk that (continued) academic frustration and related social, emotional, and behavioral problems will emerge or intensify. These problems then will undermine these (and other) students’ academic engagement and progress as part of a vicious cycle. The result will be that the school will be further behind—both academically and relative to school climate and student discipline—than when it started.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

This two-part Blog Series addressed what schools need to consider now as they plan for their students’ academic re-entry this Fall.

In Part I, we addressed why (and how) schools should validly assess—as soon as possible when students return to school—the functional, mastery-level status of all students in literacy, mathematics, and writing/language arts. Here, we recommended a step-by-step assessment process to identify groups of students who are functioning above, at, below, or well-below their current grade-level placements.

Next, we recommended that schools pool all of the assessment data for the students at each grade level, completing a “StoryBoard” process to determine the best instructional groups to assign each student to in each academic area. These assignments would then determine the best way to organize students—across the three academic areas—into classroom cohorts.

Finally, we discussed how (and why) to organize students who are functioning within one grade level of their respective grade placements into Homogeneous Skill Groups and/or Heterogeneous Comprehension or Applied Groups. We provided a Third Grade example with literacy results, integrating the data into one of the six national models that most districts will use when students return to school in the Fall.

_ _ _ _ _

In this Part II, we discussed how to use the assessment results to address the academic progress and enrichment of students who are “above” their grade-level standing, and the academic gaps of students who are below and well below their grade-level placements.

Here, we suggested that (a) most of these students were already well-known to their teachers, and (b) it was unlikely that the last three months of pandemic-driven “home-schooling” was a root cause of these students’ acceleration or decline, respectively.

At the same time, we encouraged districts and schools, once they identify these students this coming Fall, to use the following question so that these students receive an appropriate educational program:

What instructional staff and materials, and what learning environments and approaches, will strengthen and accelerate these students’ learning, enrichment, and progress?

To help answer this question, we discussed a number of possible instructional grouping patterns for the above average students.

For the below and well below grade-level functioning students, we emphasized the importance of an effective, science-to-practice multi-tiered systems of supports. At the core of this process are data-based functional assessments of struggling students’ educational histories, learning conditions, speeds of academic mastery, and current status to determine the root causes of their difficulties.

We then provided two research-to-practice blueprints to address these students’ needs (and root causes). The first blueprint, the Positive Academic Supports and Services (PASS) model, outlines a continuum of services, supports, and interventions for students who are academically struggling.

The second blueprint provided five instructional group or class assignment options for students with academic skill gaps, with a discussion of Option #5 for students with gaps that are so large that there is no way that they can benefit from or pass a course at their current grade level.

_ _ _ _ _

While there is nothing positive about the current pandemic, districts and schools know that they need to adjust in order to “survive.” These adjustments give us an opportunity to think more creatively, and to act more effectively on behalf of all students.

From an academic perspective, we need to use timely and sensitive data to determine the current functional skills of our students—especially in literacy, mathematics, and writing/language arts.

We then need to determine if students’ current academic standings were impacted by the last three months of virtual and long-distance instruction, and what instructional environments, conditions, groupings, strategies, and interventions are needed to help them to learn, progress, and succeed.

And all of this needs to occur in the context of re-establishing educational equity—especially for students of color, from homes of poverty, and for students with disabilities.

This can be done. . . and, hopefully, these last two Blogs have provided the blueprints and steps that are needed.

I appreciate your ongoing support in reading this Blog. As always, if you have comments or questions, please contact me at your convenience.

And please to take advantage of my standing offer for a free, one-hour conference call consultation with you and your team at any time.

Best,